For most of the film and TV industry, the devastating L.A.-area fires of the last week have at least avoided scorching the studios where the work largely occurs. But there’s no such consolation for many of those who work on the music side, as the professional-grade home studios of untold numbers of producers, engineers and musicians have gone up in flames alongside their actual residences.

That’s true for music producer Greg Wells, who lost his state-of-the-art Dolby Atmos mixing room and studio along with his family home in Pacific Palisades. He’s far from alone in suffering that double-whammy; producer-mixer Bob Clearmountain is another renowned Palisades resident who lost both his home and a seriously tricked-out studio, and seemingly countless musicians in Altadena suffered the dual loss of personal and professional structures.

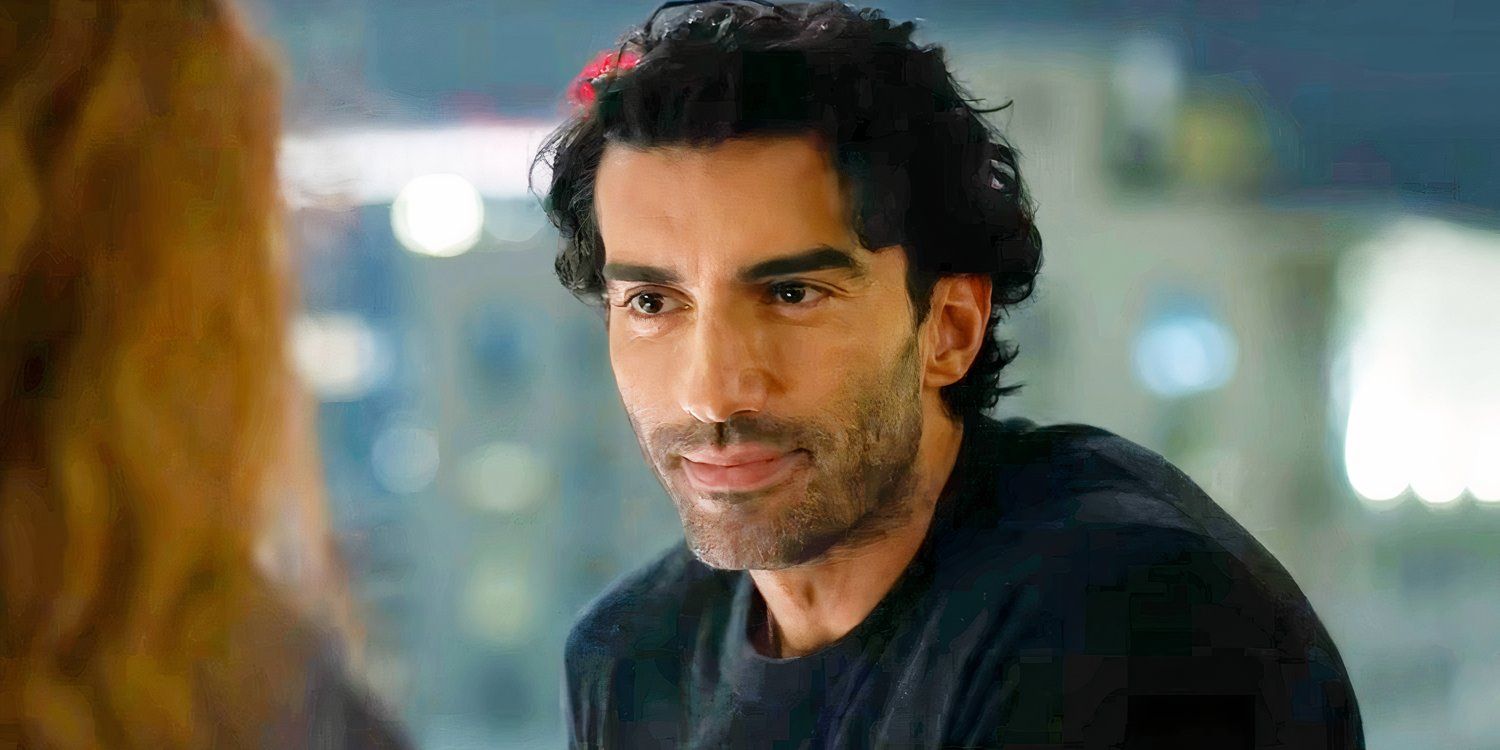

For Wells, it happened just as he was preparing to resume work on “Wicked: For Good.” In fact, just two days before disaster struck, the producer was being celebrated with a profile in Variety talking about his two and a half years of work on the films so far — including a “Wicked: Part One” soundtrack album that is still comfortably lodged in Billboard’s top 10. Bringing out the Dickensian maxim about the worst of times abutting the best hardly begins to do justice to such an abrupt reversal of fortune.

In the followup interview with Variety that Wells could never have imagined doing, he says, “I’ve never forgotten being up in a tea room where I got a little fortune and it said, ‘The only thing permanent is impermanence.’ And that’s applicable every day, but after the euphoric high of ‘Wicked’ coming out and doing what it’s doing, which is thrilling and wonderful, and then seeing just how fragile things can be… You know, I think life is supposed to be hard. I’m not sure it’s supposed to be quite this hard. But it could be so, so, so much worse than it is. I know a number of people have died, but the people immediately close to me and my family, we’re all healthy and safe — and kind of depressed and bewildered.”

Wells (who has worked with such artists as Katy Perry, Adele, Dua Lipa, Celine Dion and Twenty One Pilots, along with producing the “Greatest Showman” soundtrack) had what may have been one of the most advanced Atmos rooms in town right in his backyard. “It’s the nicest mix room I’ve ever worked in — a state-of-the-art, immersive, 7.1 Atmos room that Dolby helped me put together and tuned many times for me. It was designed by (renowned studio architect) Peter Grueneisen, who’s built seven studios for Hans Zimmer. Beyond the (ultra-modern) stuff, there were these 1950s RCA tube compressors from the Little Richard/Elvis era, really unique pieces that had always just made me salivate. It was a really kind of bucket list thing… like, I’m an old man, I’ve been doing this my whole life, and I’m finally gonna have a great mix room. But what are you gonna do?

“I had such a collection of incredible recording equipment, like a custom-made, 48-channel analog console made by Paul Wolff, who used to own API, and 17 speakers in that room, six in the ceiling, three on each wall, two on the rear wall, four huge subwoofers up front — just a magical, magical room.

“But,” he adds, “I just have to remind myself, it’s really down to the people and to the ideas, and none of that stuff makes a song better. So I’m not gonna let it define me.”

One consolation is that he had his instruments in a second studio he keeps in Santa Monica. The irony of it is that he bought that other studio from another big-name producer, Butch Walker, who offered it to him in what was literally kind of a fire sale. “Butch had two houses burn down in California. He went through it once, had to deal with the insurance company; then it happened, I think, 10 years later. And the second time he just thought, ‘Fuck this. I can’t live in California anymore.’ So he moved back to Tennessee with his wife and their child.”

Wells isn’t about to go so far as to move to Tennessee, but he thinks he may be done with Pacific Palisades, which has been a beloved place to him and his family.

“I wouldn’t put my family back in that line of fire — pardon the pun. I just wouldn’t,” he says. “Plus, that’s an area bigger than Manhattan that just got leveled, like a small nuclear bomb went off, so the rebuild factor is gonna take so long. Everyone’s gonna be doing it. It’s gonna be so loud; it’s gonna be all this shit in the air. Forget the asbestos and the smoke and everything from the stuff that did burn down, but all the new builds… There’s a million reasons why I don’t think that’s the place we can go back to, which is heartbreaking, because it’s so special. But yeah, definitely time to choose somewhere else. I personally feel like it’s just gonna happen again, and then again, and then again.”

His analogy about the devastation that just occurred in his hometown: “I just feel like we were fighting a T. Rex with toothpicks.”

He was not even around for the evacuation, everything accelerated so quickly in the Palisades. “I went out that morning for an optometry exam and I never went back. I had a kid at home, getting over pneumonia, still asleep, and my wife was there and got the alert to evacuate. We kind of just arrogantly thought, ‘There’s no rush… This is gonna be OK.’ And then I got a call from one of my older kids who grew up in the Palisades, and he said, ‘You guys have got to get out right now,’ showing me photos of just how close the flames were. So my wife got out with our passports — and that was it. But at that moment we were thinking, ‘We’ll return. We’ll be back as soon as the dust settles.'”

Wells loved the fact that his town was not necessarily a music haven. “The property taxes we pay in the Palisades, it’s so nuts, but I’ve always been into paying through the teeth to live in that neighborhood just because of the ocean air, and because I have a lot of kids. The Palisades village was like a High Street in London; you could walk and push a stroller there and eat or buy whatever you needed. The Palisades was almost like from another time, kind of Mayberry. Mort’s Deli was so fantastically weird and consistent, and I loved all the little mom-and-pop shops in the village, though that’s all been Caruso-fied now. I loved how close it was to the madness of Los Angeles, but removed from it. I love how square it is.” While noting that JJ Abrams and other entertainment big shots have homes there, “the Palisades is mostly retired teachers or people in finance,” Wells says. “There’s hardly any musicians that live there. No one really knows what I do, and I sort of like that. Hanging out with hundreds of musicians, it’s always like, ‘Oh, what are you working on?’ — there’s a competitive thing that naturally sort of appears, and that never happens there.”

As for how he feels right now, the Palisades dream is over. “It was such a shit show when that broke out, with no evacuation plan. I don’t understand why there wasn’t a plan in place, why nothing was rehearsed, but people could not drive out. I’m not complaining about the firefighters because they’re truly heroic in ways that I can’t even begin to imagine. Clearly the fire chief is saying that the city failed them. I just feel like we were hung out to dry. We knew this was gonna happen. Smaller versions of it have happened many times in the past, and it was just a question of when.

“These crazy high winds blowing in the right direction — there’s an X factor there but that’s not a mystery; that happens every year, and we’ve just been lucky that it hasn’t happened quite in the combination that it did this year. I’d say it’s also kind of the hubris of people thinking that they can live in such a dry climate, basically a desert, and ‘Let’s keep the sprinklers on. It’s gonna be OK.’ It’s so beautiful here, but there’s such risk. It really feels like sitting in front of a blowtorch with one of those massive fans they have on movie sets that could turn on at any point.”

He doesn’t purport to have all the answers, but he’s distressed at how rarely the questions came up. “What do you do? For one thing you build pipes up from the ocean and lightly desalinate the water… There’s just something so insidious about being beside the world’s biggest ocean and having this happen. I know salt water’s bad for vegetation, but I don’t think it’s as bad as what just happened.

“Actually, I think it’s like drunk driving. If I was in charge of a place like this, knowing that it was under that kind of risk, which is obvious — it’s not woo-woo, it’s not QAnon — it’s simple science. The firefighters themselves have been warning for years against this exact thing happening, in the same way that certain doctors have been warning for years about something like COVID coming through. It’s not scaremongering. It’s like that Ibsen play, ‘Enemy of the People,’ where only one guy has the nerve to say the water in this new spa that is supposed to save the town’s economy is toxic and people are gonna get sick. It really does kind of remind me of that.”

Wells and his family are riding out the aftermath further up the coast, though he was returning to Santa Monica when he spoke with Variety, making a trip to clear out the instruments from his studio. There is some time to figure out where his work on “Wicked: For Good” will resume, although not a lot.

“Everything’s backed up in a safe way,” he says of the MIDI demos that he did for both films’ soundtracks prior to their shooting. “The clock is ticking because we’re trying to record the orchestra in May this year; last year (for ‘Part One’) it was June, so there’s a lot to do between now and then. And I’ve lost all my computers except for one. There’s just a lot to replace and figure out where I’m gonna do this and how I’m gonna do it. And that’s all manageable. I’ll figure it out.”

More pressing are immediate issues like the kids’ schooling, with no fixed base for the family at present. He’s still in shock. “It’s really not until I say to somebody else what just happened to us, and then I see it in their face, that I realize the full heaviness of what we’re going through. Because it doesn’t fully feel like it’s happening. It’s so, so surreal.

“There’s a trick that you can play with people — it’s amazing how the brain works this way — where you’re sitting at a table, you look at everything on the table, and you get the person playing the game to cover their eyes, then you remove one thing from the table,. Then they open their eyes and it’s really hard for them to tell what’s missing because they haven’t seen the thing leave. It’s so surreal then to find out that, like, a plate of food has gone missing or whatever.

“There’s just that weird thing of not having closure, of not saying goodbye to a thing. This is that experience, exponentially ramped up.”

(Read Variety‘s original interview with Wells about working on “Wicked” here.)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·