If Travis Bickle were real and alive today, he would not be a taxi driver but more likely be sitting in his parents’ basement, exploring the dark, misogynistic depths of the internet.

“We call them incels now,” reflects Paul Schrader, who wrote the screenplay for Taxi Driver, released 50 years ago on Sunday. “‘Incels’ wasn’t a word at that time but it is these guys who are lonely, who see themselves unable to make contact with women, have a repressed backlog of anger and resentment and imagine some kind of glorious transcendent transformation through violence.”

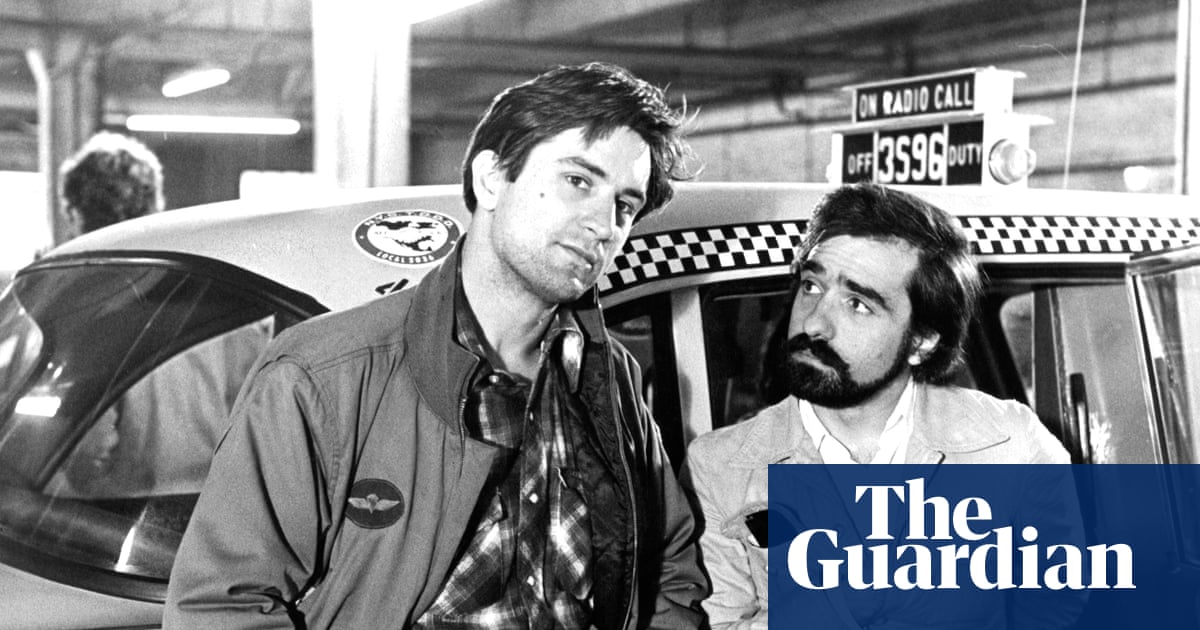

The film, directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel and Cybill Shepherd, is a masterpiece of urban alienation. It follows Bickle, a lonely, mentally unstable Vietnam war veteran working as a New York cab driver who, disturbed by the crime, corruption and moral decay he sees around him, develops a dangerous saviour complex.

Bickle narrates: “All the animals come out at night: whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies – sick, venal. Someday, a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.”

Raised in Grand Rapids, Michigan, by a Calvinist family, Schrader did not see a movie until he was 17. Then he became a film critic and a protege of Pauline Kael of the New Yorker magazine. But at 26 he hit a rough patch and wrote Taxi Driver as a form of self-therapy.

Speaking by phone from New York, the 79-year-old recalls: “I lost my job, left my wife, left the girl I left my wife for, didn’t have a place to live, was drinking considerably, was living in my car and had a gun in the car. This went on for a couple of weeks.”

He would haunt New York’s adult cinemas because they were open day and night. “You could sleep four or five hours in the balcony of the old porn palaces. You would occasionally be awoken by people around you but you could get a few hours of sleep that way.”

One day Schrader felt a pain in his stomach, went to an emergency room and was found to have a bleeding ulcer. He was 26. “In the hospital this image came to me of a taxi cab and I said, ‘That’s me: I’m this kid locked up in this yellow box floating in the sewer, who looks like he’s surrounded by people when he’s absolutely alone.’

“Whereas other people at that time associated taxi drivers with your garrulous, friendly brother-in-law, I saw in Taxi Driver the heart and soul of Dostoevsky’s Underground Man.”

Before he started writing, Schrader reread works by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. “I wanted to take this character, who had existed in European literature and American literature – which is the underground man, the existential hero – and bring him to film.”

He got the first draft written in just 10 days. “I wrote one draft and immediately started rewriting. I needed to exorcise this character. If I didn’t write about him, I’m afraid I might become him.”

Among Taxi Driver’s many memorable scenes is Bickle, his head shaved into a mohawk, attending a political rally with the intention of assassinating a presidential candidate. But Secret Service agents spot Bickle putting his hand inside his jacket and approach him, which escalates to a chase.

An inspiration for this was Sara Jane Moore’s attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford in San Francisco in September 1975. “She took a shot at Gerald Ford. She missed and was on the cover of Newsweek magazine the next week.

“That’s where I said, ‘That’s what our culture has come down to? You shoot at the president, you miss, and now you’re on the cover of the largest publication in the country.’ That’s where the early ending of Taxi Driver comes: the irony of becoming famous.”

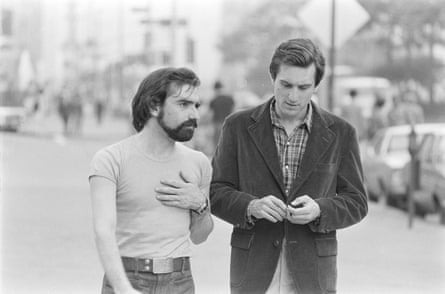

Schrader offered the screenplay to the film director Brian De Palma, who passed it on to Scorsese, who immediately believed in it and even saw something of himself in the underground man. Who, then, would play Bickle? Harvey Keitel was the early favourite. Schrader says: “Bob had been in Mean Streets but Marty went further back with Harvey.

“I had gotten [co-producers] Julia and Michael Phillips involved. He showed us an early cut of Mean Streets. Julia and I walked out and we both looked at each other and said, ‘It’s not Harvey, it’s Bob.’ Marty recognised that was the truth but then he had a little problem with what to do about Harvey.”

Schrader, Scorsese and De Niro did not talk much about Bickle ahead of production. They did not need to. “We all knew this kid,” Schrader says.

Schrader originally wrote the character of Sport, a pimp, as Black to reflect what he had observed on the streets. But executives at Columbia Pictures demanded the role be changed to white, fearing that a white protagonist killing only Black people in the final shootout would incite riots and cause liability.

“I had written the pimp Black because he [Bickle] is a racist character and he kills Black people. The studio said, ‘If he only kills Black people, you’re gonna have violence in the theatre.’ Then all of a sudden there was a role for Harvey.”

Keitel asked Schrader to find a real life white pimp to model the character on. “I never did find the Great White Pimp,” Schrader admits, but Keitel took the role anyway. Foster, just 12 years old, was cast as the young sex worker Iris and held her own when she and De Niro ad-libbed dialogue.

There was more improvisation required when Bickle stares at himself in a mirror and imagines a confrontation. Schrader explains: “It was in the script that he takes the gun, plays with it in the mirror, points it at the mirror, pretends to shoot it, talks to himself.

“‘What does he say to himself?’ Bobby asked me. ‘What line would it be?’ I said, ‘Hey, it’s like when you’re eight years old and you’re playing cowboy, you’re shooting in the mirror and say, “Hey, gotcha! I’m faster than you!” Stuff like that.’”

When the moment arrived, De Niro came up with a line for the ages: “You talkin’ to me?” In 2016, at a screening of Taxi Driver at the Tribeca film festival in New York, he told fans: “Every day for 40 fucking years, at least one of you has come up to me and said – what do you think – ‘You talkin’ to me?’”

To achieve an R rating without cutting footage, Scorsese desaturated the colour of the final shootout, turning the bright red blood into a “tabloid” brown. Also vital was the musical score by composer Bernard Herrmann, who completed the recording sessions hours before his death.

Taxi Driver was released on 8 February 1976. Schrader remembers talking to someone at Columbia Pictures who thought the film would flop but feeling more optimistic himself. “We made a $20 bet and, on the day it opened at the Coronet, I went over. I wanted to be there, first day, first screening.

“It was just about ready to start and I noticed around the theatre there’s a line and I thought, ‘Oh fuck, they had a problem and they’re not letting people in.’ In fact, that was the line for the show two hours later. Right about the time I walked in, the words Taxi Driver came up with that music and the audience applauded. This is the first screening in New York, so all that word of mouth had been buzzing around.”

The movie’s debut at the 1976 Cannes film festival drew boos and some walkouts. The playwright Tennessee Williams, the then jury president, said: “Films should not take a voluptuous pleasure in spilling blood and lingering on terrible cruelties as though one were at a Roman circus.”

Foster has recalled that, apart from a press conference, Scorsese and De Niro hunkered down in their hotel rooms, worrying that everyone would hate the film. That left the young Foster, who could speak French, to do media interviews. Yet Taxi Driver still won Cannes’s top honour, the Palme d’Or.

It also struck a chord with the Holden Caulfields of the world – young men full of resentment, anger, self-loathing and an inability to connect. Schrader says: “It hit the bullseye of the zeitgeist but you cannot plan to do that. Either it happens or it doesn’t.

“I remember one day in my office, I came in and my secretary said, ‘Don’t go in there.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ She said, ‘It’s one of those kids.’ So I went in and there was a kid there and he had jumped over the fence and come to my office. I asked him what he wanted. He said, ‘How did you find out about us?’ I quickly checked to see if he had a gun on him and said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘That movie, Taxi Driver – who told you about me?’

“I said, ‘Honestly, no one told me about you; there are a lot more of you than you think.’ Then I said to him, ‘Have you ever been on a movie lot?’ I said, ‘Well, let’s get a golf cart, I’ll show you around the movie sets.’ He said, ‘Oh, that would be cool.’ We went around in a golf cart and I had a security guard come over to me and say, ‘Mr Schrader, you’re needed back.’”

Schrader’s interloper was not alone in taking Taxi Driver personally. In March 1981, John Hinckley, who had become obsessed with the movie and had been stalking Foster, tried to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in an effort to impress her. Foster was subjected to intense, unwanted media scrutiny at the time and has consistently refused to comment publicly on the incident.

Years later, Schrader recounts, De Niro asked if they could bring Bickle back in a sequel. “I said, ‘Bob, first of all he’s dead, but if he wasn’t dead, he’s not riding a taxi any more. He’s sitting up in his cabin in Montana setting off bombs and his name is Ted Kaczynski.’”

A generation later, the natural heir is the disaffected young man hunched over his laptop, wandering the manosphere and potentially exploding into violence. “There is now a whole recognised culture of incels. It’s sort of curious. These lonely kids who would sit and fester in their rooms now fester in their rooms and talk to other lonely kids who are also festering in their rooms. Does this alleviate some of their psychosis or does it heighten it? I don’t know which.”

Such cultural relevance helps explain why Taxi Driver has endured for 50 years and will doubtless endure for 50 more. Schrader muses: “Every generation finds it. When someone comes up to me and says, ‘Taxi Driver changed my life,’ I always say to them, ‘Let me guess, you saw it when you were 15, and they say, ‘How did you know?’

“I say, ‘Fifteen is the age where you’ve been watching action films and you’ve heard about this film and it’s the first time you realise you can have an action film that isn’t just about action.’ Every generation of young men in particular seem to find that through that film. There are few other films like it that epitomise a certain point in your life and so it is a film that won’t die.”

Scorsese went on to make films including Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Cape Fear, Casino, The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street. De Niro starred in The Deer Hunter, Raging Bull, Once Upon a Time in America, Goodfellas, Meet the Parents and many others.

Schrader, who continued to write screenplays and also directed films such as Blue Collar, American Gigolo and First Reformed, comments: “Bobby should have taken more chances. He got heavily involved in real estate and that became an excuse to take the money gigs.

“Marty said to somebody once, ‘I paint frescoes: I paint the ceiling, I paint the floor; Paul paints Dutch miniatures.’ If you want to paint frescoes, you need a lot of money – a lot more than I need to do Dutch miniatures.”

For all its modern resonance, Taxi Driver also stands as a precious time capsule that washed down to 2026 from an America disillusioned by the Watergate scandal and Vietnam war. It is a portrait of a city – the New York of high crime and hustlers that nearly went bankrupt in 1975 – but also a portrait of a moment.

Richard Brody, a film critic at the New Yorker, comments: “For me, the most powerful experience of Taxi Driver is not rewatching it; it’s having watched it just about in its time as a teenager and feeling it had concentrated all the craziness of the time into that movie – a kind of requiem for the political and social frenzies of the late 60s and early 70s that by the time of the making of Taxi Driver had spun out of politics and spun into an inchoate but grave crisis.

“Taxi Driver gave me the sense, when I saw it, that Scorsese felt a breaking point. He felt the old latches ripped off and volatile, unpredictable energies that had formerly been directly channeled now unleashed.”

3 hours ago

496

3 hours ago

496

English (US) ·

English (US) ·