Striving for realism, Timothée Chalamet knew what the scene required. “I’m really getting in the guy’s face and I’m really trying to get him angry with me,” the lead actor recalled recently about the making of Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme. “I was saying to Josh, ‘He’s not getting angry with me, he’s not getting angry with me.’”

But it turned out the unnamed extra had been paying attention. Chalamet added: “I did another take, and then the guy said, ‘I was just in jail for 30 years. You really don’t want to fuck with me. You don’t want to see me angry.’ I said to Josh, ‘Holy shit, who do you have me opposite, man?’”

The answer was that Safdie had cast a non-actor – one of many who have roles in Marty Supreme, a fictionalised homage to the mid-20th century table tennis player Marty Reisman. Similarly, Paul Thomas Anderson used people with no prior acting experience for his comedy action thriller One Battle After Another.

Safdie and Anderson are following in a long tradition of directors using non-professionals to achieve a level of authenticity based on lived experience and physical presence rather than theatrical technique. It has run the gamut from early Soviet cinema and Italian neorealism to a fleeting appearance by Donald Trump in Home Alone 2.

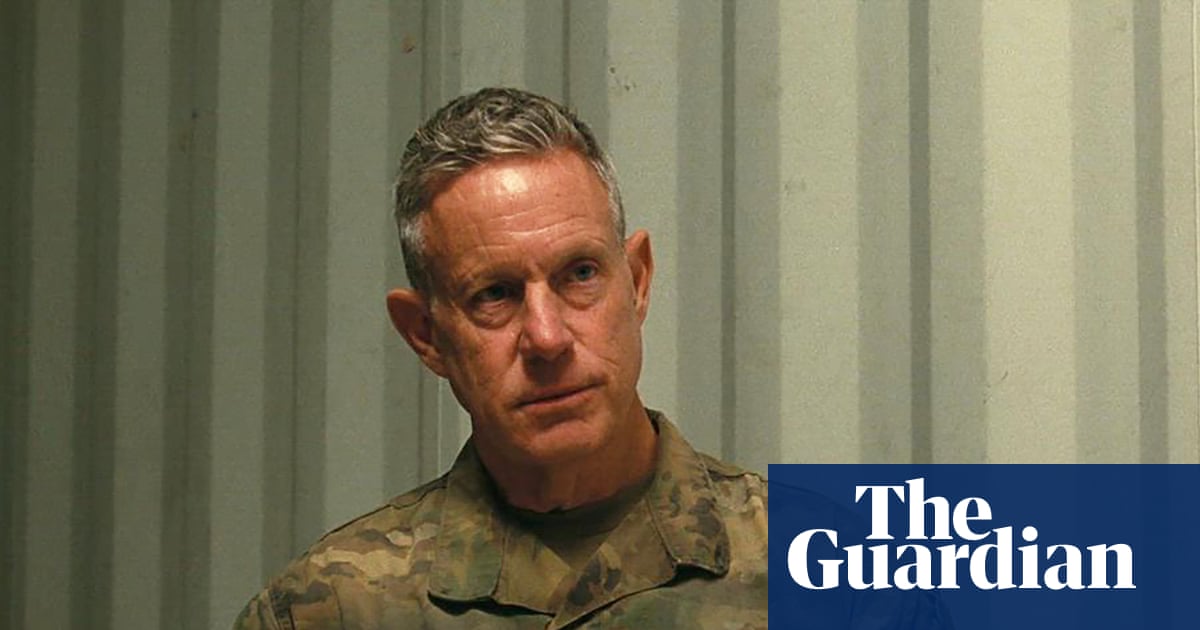

One Battle After Another has marquee names aplenty – Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Benicio Del Toro, Teyana Taylor – but also a striking cameo by James Raterman, a retired Secret Service and Department of Homeland Security Investigations special agent. Raterman was spotted by Anderson after taking part in The Trade, a documentary series about the opioid crisis and human trafficking.

Despite his lack of acting experience, he threw himself wholly into the role of Colonel Danvers. “It’s a job and you have to work at it,” Raterman says by phone from Columbus, Ohio. “The good thing with myself and Paul is he’s so collaborative. He allowed me with the other actors to pull it off the cuff.

“This is one of the best pieces of acting advice that I’ve received and I received it from Mr Anderson. He said, Jim, when you read the script, don’t pay attention to the words on the page; pay attention to what is it that I need you to do at that particular time. Honestly, I could have probably gone to film school and studied for years and years and maybe got that same piece of advice but, coming from somebody like Paul Thomas Anderson, it put you in a different frame of mind.”

Raterman has nothing but praise for how the professional actors on One Battle After Another welcomed him into the fold. “These are amazing A-list actors that have no problem whatsoever taking you under their wing and treating you like a family member and wanting you to elevate in such a way that the whole project gets elevated.

“You never felt like a stranger, you never feel like an outsider and that started at the top. It started with Paul Thomas Anderson and that’s the way he is so everybody takes his lead. I don’t know if everybody has the same experience but they treated me like a family member from day one until even today. It was an incredible, fun, enjoyable experience. We laughed, we bonded, made some incredible friendships.”

One Battle After Another also features Paul Grimstad, a musician, writer and professor of humanities at Yale University. For years he avoided on-camera work following an early part in his roommate Ronald Bronstein’s indie film Frownland. But then Bronstein passed Grimstad’s name to casting director Cassandra Kulukundis, who immediately saw a natural fit with the character Howard Sommerville.

Grimstad, 52, told the New York Times newspaper that “acting was incredibly fun” and said his years as a university lecturer were ideal preparation. “There is an element of verbal performance in teaching. I’m not talking about over-the-top showmanship, but a certain way of animating a book.”

Grimstad also appears in Marty Supreme, primarily set in New York during the early 1950s, along with non-actors including the supermarket magnate John Catsimatidis, former basketball players George Gervin and Tracy McGrady, essayist and novelist Pico Iyer, playwright David Mamet, fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, Shark Tank regular Kevin O’Leary and French high wire artist Philippe Petit.

Catsimatidis, 77, says: “Josh Safdie says he met me or saw me when I was running for mayor in 2013 and I was what you call a New York character and he was looking for characters. Being a New York character, I guess I qualify. The lines that I used are things that I do in real life, so I wasn’t acting: that was me.”

He reflects: “I enjoyed it. They worked me to midnight. They did one scene 20 times over. Josh Safdie was a great director. He’s a perfectionist and I appreciate somebody that wants perfection.”

Petit, who in 1974 walked between the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York on a tightrope, says: “Many directors are interested in what I would call the freshness of the non-actors. Very often when you take a non-actor instead of a movie star for a movie, that non-actor doesn’t have the training and some of it could be negative but I also very much like to have a complete newcomer to do something important. It’s sometimes a revelation.”

McGrady, 46, who played for teams including the Orlando Magic and Houston Rockets, adds via email: “I think we bring something real. There’s an authenticity that comes from people who’ve lived a different life and bring that energy naturally. For me, I’m just being myself and bringing my own experience to the role. Sometimes that rawness adds something special (hopefully).”

Gervin, 73, a former San Antonio Spurs player dubbed the “Iceman”, says: “I met Josh, the director, a few years ago at a card show, and we shook hands and spoke and the next thing I know, I’m getting a call from the studio that Josh would like me to play a role in the movie.”

Gervin plays Lawrence, the owner of a table tennis parlour in midtown Manhattan. He says of Safdie: “He’s very careful in who he picks. He said, when I met George Gervin, George was so warm that he made me feel that he can run an orphanage. He knows that I have two charter schools so I’m around kids all the time and educate them. Did he take a chance? Probably so but he was in control of what goes in and what goes out and I’m glad he had that kind of confidence in me.”

Gervin found that film-making involves long hours. “I went on set at three in the afternoon and didn’t finish till about four in the morning. I wasn’t used to that kind of endurance but it only took me a day to do the little part that I had in the movie. You have a different respect for someone like Timothée, who’s the main character and he was up 12 hours with me. You have to be mentally and physically strong to accomplish what he did. I am truly impressed with what goes into making movies.”

Safdie envisioned Lawrence’s club as a safe place for misfits, which was a gift for casting director Jennifer Venditti to study 1950s photographs and tell its story through faces. Her work on Marty Supreme has made the shortlist for the new Oscar category of best casting.

Venditti, who started street casting 25 years ago when she was in the fashion industry, is a longtime collaborator with both Josh Safdie and his film-maker brother, Benny. She cast the ex-basketball player Kevin Garnett as himself in the Safdies’ 2019 crime thriller Uncut Gems.

She says by phone: “One of our signature things is this idea that we are looking to recreate the cinema of life. Sometimes we love actors and characters but sometimes in the pool of actors we can’t find the texture that’s needed to build the authenticity of the world that we’re exploring.”

Venditti adds: “We’re always trying to create this alchemy of these incredible actors who know where scenes are going and then these wild people who can add the texture and mystery of they don’t know where the scene’s going and it’s the tension between those two things that creates the excitement in Josh’s films. It’s how we see the world and how we want to see it on screen.”

How do established actors generally respond? “At first, if you’re like a very trained actor, it can be alarming in a sense of like, wait, this person’s not following the rules or talking over me. But Josh is such an amazing director that creates such a safe environment, they trust him and they then realise that kind of wildness is lending to their performance.”

The process works both ways, Venditti notes. “The scene partner makes these real people good. Timothée is in every scene showing up with his dedication and his focus and his level of mastery. They are so good because they’re in a scene with someone that’s demanding that of them then they rise to meet each other.”

The use of non-actors dates back to early Soviet movies such as Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and October in the 1920s. Italian neorealist films such as Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves frequently used non-actors to represent the working class and used post-production dubbing by professional voice actors to ensure clear dialogue and emotional control.

Notable US and UK examples include The Best Years of Our Lives, featuring Harold Russell, a second world war veteran who lost both hands; The Killing Fields with Haing S Ngor, a Cambodian doctor and genocide survivor with no acting experience; and United 93, in which real flight crew, air traffic controllers and military personnel played themselves.

Catherine O’Rawe, author of The Non-Professional Actor: Italian Neorealist Cinema and Beyond and a professor of Italian film and culture at the University of Bristol in Britain, says: “The non-professional is such an interesting figure. It forces us to look at the question of what is acting, what is performance? Is it just standing up and saying a line? What is it that good acting brings? Some of the non-actors, for example, in the films of postwar Italy were not necessarily what we would think of as brilliant actors but had an amazing face that the director loved.”

But the practice has also been controversial. Four-year-old Victoire Thivisol won the best actress award at the 1996 Venice Film Festival for her role in Ponette, about a child who has lost her mother. O’Rawe says: “The performance was so affecting that she won this award and the director collected it on her behalf and got booed by the critics and audience because it’s seen as an affront to profession: if a four-year-old can do this then what is the craft of acting worth?”

In 2018 Yalitza Aparicio made her acting debut in Alfonso Cuarón’s drama Roma, earning a nomination for the Oscar for best actress. O’Rawe comments: “She was a total non-actor and that was a source of great fascination among the press but sometimes people are a bit uncomfortable that someone with no training can actually be nominated for awards because then for professional actors it can mean, well, why have we spent our lives training and doing all this performance study if somebody can just walk off the streets and win an Oscar?”

But these accidental stars often find it impossible to build a lasting career. They can be propelled into the spotlight at the Oscars only to be left without a safety net once the production cycle ends. The industry may fall in love with an “unspoiled” face for a single project, but it rarely offers the infrastructure needed to turn a singular moment of authenticity into a profession.

O’Rawe reflects: “These debates have gone on and they come back at different times but there is always this undercurrent of both the resentment and also that the industry might love these people once but they’re not going to support them.

“There are so many cases of these actors who after one big moment, sometimes even winning an award, will find that they can’t get jobs because they’re not trained, don’t have any contacts in the film industry or don’t have any agents or managers or people looking after them. It can be very difficult to build or sustain a career.”

3 hours ago

268

3 hours ago

268

English (US) ·

English (US) ·