Like it or not, horror gaming is often built on jump scares. Deriding a good cheap scare ignores the endorphin rush that draws so many players to the genre, in the same way that the "elevated horror" trend forfeits some of the soul of schlocky slasher flicks and ghost movies. Don’t get me wrong, Silent Hill and Alan Wake deserve their flowers - but even those games would wither on the screen if Pyramid Head didn’t bust through a wall from time to time.

One unsung jump scare game in particular pioneered horror in the internet age, blazing everywhere from nascent social media to major television networks. In fact, if you had an internet connection circa 2005, there’s a good chance you played it. Alas, it was too ahead of its time, too successful at leveraging virality before viral horror was sought after. Next time you see a streamer throw their headphones across the room in fright, beware: the spirit of Scary Maze Game is right behind you.

Better known by this honorific title, The Maze was created by internet prankster Jeremy Winterrowd in the early aughts. You can still play it online via the Internet Archive if you'd like to experience it personally before I spoil it for you. After taunting potential players on its home screen (“How steady is your hand?”) and suggesting that turning your volume up will help, somehow, The Maze sticks your cursor in a maze of simple blue-on-black rectangles. Two levels pass without much incident, before a narrow tunnel at the end of level three demands you to lean in. Your attention is swiftly punished by a close-up of Linda Blair from The Exorcist and two sharp screams. If all went to plan, your victim would tumble out of their seat in sweet, hilarious panic. This is not a game you were meant to play yourself.

Like Rick Rolls and chain emails, "screamers" propagated from the ability to share media with little pretext. Screamers existed before The Maze in the form of short animations and videos—even inspiring a series of German energy drink commercials—but Winterrowd’s game set itself apart by dint of being a game. You had to initiate the jump scare yourself, and doing so required sharp focus. It was less like watching a car crash and more like cranking a jack-in-the-box.

Understandably, reactions were big. And if you couldn’t stand by your victim and watch their freakout yourself, you were in luck, because there was this shiny new website called YouTube. Reaction videos are The Maze’s first milestone contribution to online horror, and they were responsible for the game’s mainstream popularity. Internet historian Jake Lee found Maze reaction videos as early 2006, which were shown on Web Junk, The Soup, and America’s Funniest Home Videos (which was the style at the time) and parodied on Saturday Night Live in 2010.

This newfound fascination with fear seemed destined to collide with let’s plays, a video format just coming into vogue. But rather than the quiet dread of early horror let’s plays like I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, the rise of Scary Maze Game vids whetted the internet’s appetite for pure terror. Sure enough, the YouTube of the following decade fed on loud-screaming creators and reaction-heavy games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Slender, and eventually Five Nights at Freddy’s, the holy grail of them all.

For more hoity-toity horror fans, The Maze’s virality demonstrated another kind of horror made possible by the internet: the intrusion of horror into the mundane. Writing for Den of Geek, Alec Bojalad attributed the popularity of internet screamers to the mystery of the early web. Even The Maze’s crude jumpscare was buoyed by mystery, with legends of a secret fourth level attracting their own attention and calling to mind modern ARGs.

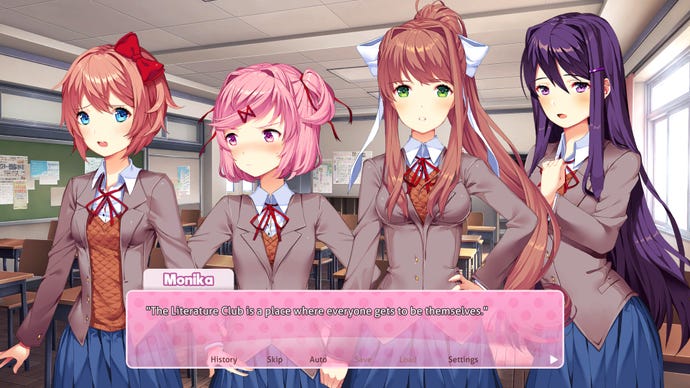

As the internet became less mysterious, surprise horror games became stealthier. They modified The Maze’s strategy to extract not just intense focus, but emotional attachment. Can Your Pet, a Flash game about raising an adorable duck and then butchering it, came out the same year as the Scary Maze Game SNL sketch, and Doki Doki Literature Club did the same thing more responsibly in 2017. Newer games—including this year’s KinitoPET, which wears the skin of early web applications—even have streamer modes in anticipation of becoming viral.

Unlike those games, The Maze doesn’t really have a point to make. It’s purely experimental. Because of that, and maybe because Flash games are subject to perpetual dismissal, it never found purchase among the horror greats of the early web. When it’s called a game at all, it’s put in scare quotes. Jeremy Winterrowd chased his own notoriety with a few more prank games following The Maze’s success, all of which flopped as his name became associated with the surprise his games relied on. His blog became a quiet forum for posting reaction videos before he vanished from social media in 2019.

Winterrowd’s influence may be unsung, but it’s easily felt. The Maze is internet horror in its purest form, with the tropes and influences of the past two decades stripped away, and thus it feels rudimentary to play now. Still, if you’re looking to recapture the feeling of The Maze, try Dreader. It’s more familiar to fans of modern horror, and a little less magical. But it keeps the most important parts of the screamer - it’s short, loud, surprising, and free - and it requires your undivided attention.

12 hours ago

6

12 hours ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·