What if a man… were also a wolf? It’s a question that’s compelled filmmakers for more than 100 years, inspiring a monster movie classic (George Waggner’s “The Wolf Man”), a handful of enduring cult hits (“An American Werewolf in London,” “Ginger Snaps,” etc.), and an endless series of howlingly bad Hollywood misfires from otherwise reliable directors. Mike Nichols’ “Wolf” was seductively bizarre enough to work on its own terms, but Joe Johnston’s “The Wolfman” — a $150 million Benicio del Toro vehicle that confirmed Universal’s desperation to update its oldest horror IP — was neutered by corporate interference in similar fashion to how Miramax had declawed Wes Craven’s “Cursed” a few years earlier. And of course, the “Dark Universe” mega-franchise that was meant to revive so many of Lon Chaney Jr.’s most immortal roles imploded before the rise of its first full moon.

In that light, perhaps the most impressive thing about Leigh Whannell’s new “Wolf Man” is that — despite being unburdened by the budget and world-building of its predecessors — this deeply un-fun creature feature somehow manages to be every bit as dysfunctional as its studio’s other recent attempts to make lycanthropy great again. Worse, it’s dysfunctional in so many of the same ways: Murky, witless, and plagued by laughable special effects (the prosthetics are crafted with obvious skill, but the hyper-realism of their design can’t help but curdle into comedy after the film abandons its emotional core).

That’s a dagger to the heart of a reboot so eager to do something different with its material; so eager to replicate how successfully Whannell re-imagined “The Invisible Man” for the 21st century by marrying timeless fears to modern sensitivities. Working from a script he co-wrote with his wife Corbett Tuck, the director asks the defining question of its sub-genre with a radical new emphasis (one less focused on the animal inside of us than the humanity that keeps it at bay), only to arrive at an all too familiar answer. What if a man were also a wolf? It would look very dumb.

And yet, you don’t have to use the Wolf Vision™ that Wannell frequently showcases throughout the film to see that his take on the classic monster had the potential to be something a bit smarter. The pieces are there, even if “Wolf Man” doesn’t have any real interest in playing with them.

Like the vast majority of modern studio horror movies, “Wolf Man” is effectively just a trauma metaphor stretched into three acts. The first of them holds all of the story’s promise, as a tense prologue introduces us to a pre-teen kid named Blake, whose military-like father (Sam Jaeger, all menacing toxic machismo) is hell-bent upon teaching his son how to survive the world on his own. I can’t explain why Blake’s dad insists on raising his son in a rural pocket of Nowhere, Oregon, where the locals have been stalked by a man-eating creature of some kind, especially since he’s so preoccupied with keeping his only child safe from harm. But determined parents aren’t necessarily good ones.

Indeed, that becomes a running theme in a movie that never has enough room to stretch its legs. When the story picks up 30 years later, it finds that Blake (Christopher Abbott), now a neurotic father himself, is so terrified of his daughter getting hurt that it seems to affect his decision-making. Case in point: When Blake receives a letter stating that his missing father has been declared legally deceased, his first thought is to ditch San Francisco, load young Ginger (Matilda Firth) and his journalist wife Charlotte (Julia Garner) into a U-Haul van, and force them to spend the summer in the same house that scared him to death as a kid. In the same off-the-grid stretch of Oregon hillside (New Zealand) that inspired his dad to make panicked CB radio calls every night before he finally disappeared into the woods. As a parent, few things are worse than the thought of your own child being afraid of you. For whatever reason, Blake is drawn to discover what those things might be. Spoiler alert: One of them is a wolf man.

It’s a curious but appreciably intimate way to set up the stakes of a not-so-classic monster movie, as Whannell grounds the horror to come in an eternal crisis that previous generations of men were expected to resolve on less emotional terms. How do we square our animal instinct for safety and providing… with our impetus to love? How do we balance keeping our children alive without betraying the part of ourselves — and each other — that has evolved beyond the most basic demands of survival?

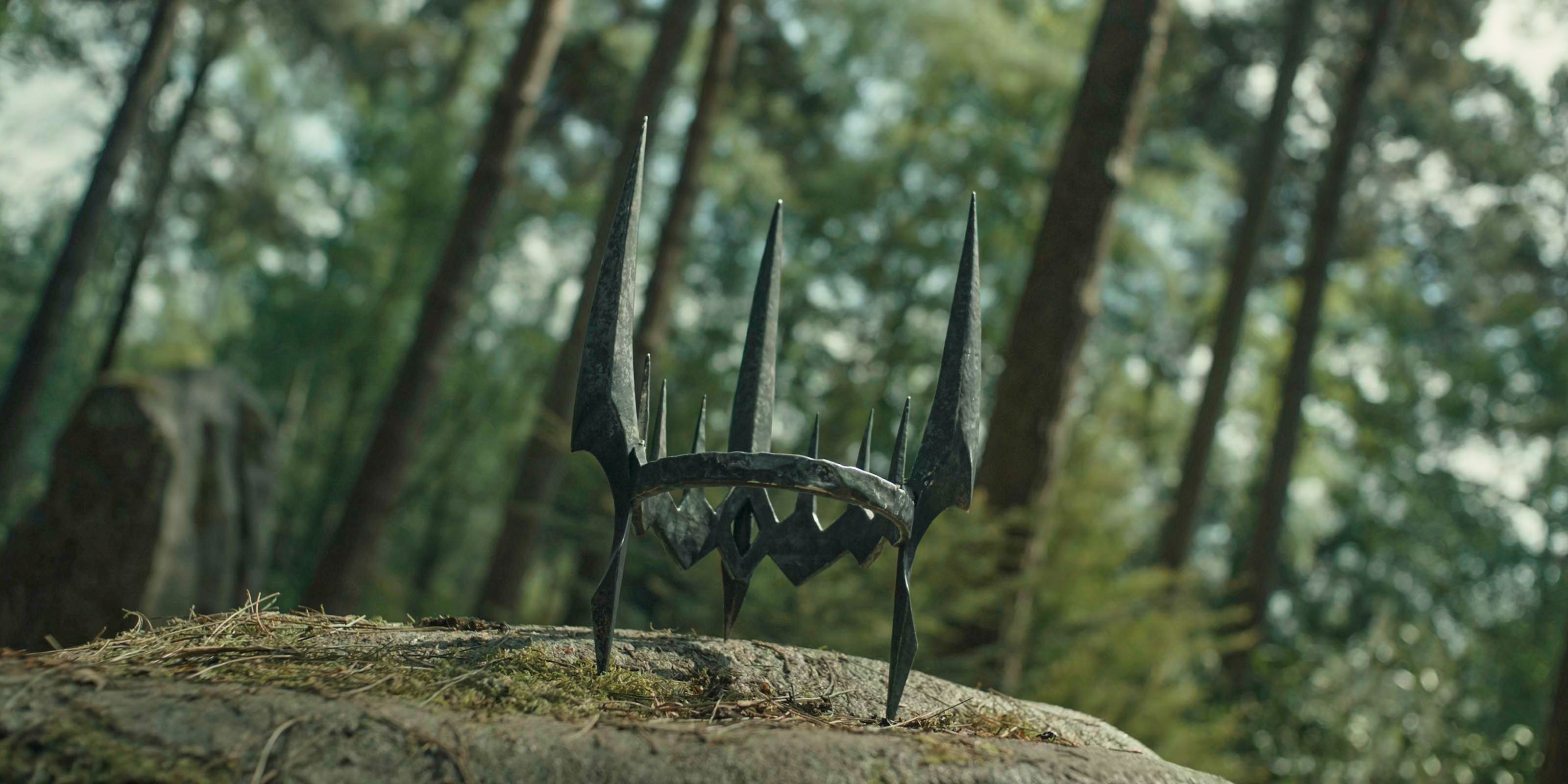

“Wolf Man”Photo Credit: Nicola Dove/Univer

“Wolf Man”Photo Credit: Nicola Dove/UniverAs an unemployed writer who’s adopted a conventionally maternal role in his family (to the chagrin of his wife, whose professional ambitions have put her at a distance from their daughter), Blake feels like something of a dickless beta male at the start of this movie. I shudder to imagine the reactionary YouTube commentaries that will be inspired by the scene where he happily wears his daughter’s lipstick.

When Blake gets bitten by a werewolf on the road to his dad’s farmhouse (a werewolf that only he will be able to stop from eating Charlotte and Ginger), it triggers a civil war between the angels of his nature. A civil war whose progress is measured in back hair, bad skin, and some newly heightened senses. “Hills Fever” is a hell of a drug! Holed up inside his childhood home and desperate to keep his people safe until sunrise, Blake doesn’t just have to fend off the beast outside, he also has to tame the beast within. (For her part, Charlotte’s only job is to be punished for pursuing her career, and then rewarded for reclaiming a more conservative maternal role.)

It’s a cleverly intimate premise that’s very much in line with Whannell’s approach to “The Invisible Man” (which would have made a fitting title for “Wolf Man” as well), and one that Abbott is game to explore. Pivoting a werewolf movie away from the id in favor of the superego is sort of like making a vampire movie about the moral victory of being vegan, but Abbott is the kind of actor who brings his own mottled truth to each moment, and his early scenes with Garner are layered with a level of lived-in honesty that is almost unheard of in recent studio horror. Abbott’s seeming allergy to emotional fakeness is by far the greatest asset that “Wolf Man” has, but — as those brave few of us who saw “Kraven the Hunter” might recall — it can also be a major liability to any film that loses faith in itself. And as “Wolf Man” abandons its nuances in favor of becoming a dim, cramped, and tedious siege movie about a growly creature of some kind trying to eat the people inside a rotted farmhouse, the reality of Abbott’s performance is consumed by the ridiculousness of watching him turn into a wet dog.

Blake’s inner turmoil is reflected in the film’s (lack of) tension between intergenerational trauma and cheap suspense, which is less a tug-of-war than an unconditional surrender. The darkened farm house is a dull location for the nightmare that “Wolf Man” visits upon it, and the monster at its door never feels like much of a real threat. For one thing, it’s too stupid to simply break in through a window. For another, it becomes less frightening with every step of Blake’s own transformation, as our hero’s appearance prepares us to deal with the terror outside. New hair in weird places, problems with his teeth, a growing inability to understand his wife… steel yourselves for the unimaginable horror of a man nearing 40!

Tempting as it is to applaud Whannell for eschewing bad CGI or ersatz Rick Baker effects, the ultra-grounded approach is a poor fit for a movie that feels like it’s been cut to the bone, leaving us with little more than some very expected plot developments and a handful of extremely uninspired duels between werewolves. “Wolf Man” is a soft-hearted story that’s been squeezed into the shape of a lean-and-mean January programmer, and while Whannell manages to eke a few decent moments from that situation (a pitch-black barn encounter is almost satisfying enough to make up for an underwhelming greenhouse setpiece that fails to generate any suspense), most of the jolts lack the same thought that went into the film’s disregarded story, and the occasional bits of R-rated gore aren’t sick enough to make up the balance. If anything, the scene where Blake starts to gnaw his own arm off is the most relatable part of the movie.

A semi-feral drama about parental fears that isn’t remotely scary enough to catalyze those concerns into the action it puts on screen, “Wolf Man” runs away from its potential with its tail between its legs. “There is nothing here worth dying for,” reads the “no trespassing” sign on the childhood home where Blake inexplicably returns with his wife and daughter. There’s nothing here worth watching for either.

Grade: C-

Universal Pictures will release “Wolf Man” in theaters on Friday, January 17.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.

2 days ago

24

2 days ago

24

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25623086/247270_Apple_watch_series_10_AKrales_0631.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·