It’s been said that all monster movies fit into at least one of three categories. Werewolf movies play on the notion that within every man lives a beast waiting to be unleashed. Vampire films tap into our collective fear of the unknown, which can encompass everything from the threat of disease to the perception of strangers as potential predators. And Frankenstein stories explore the risks when man plays God, creating life and facing the consequences.

Blumhouse’s shrewd 2020 reboot of the classic Universal horror film “The Invisible Man” cleverly played off the latter two, as Elisabeth Moss embodied a woman trying to escape an abusive relationship with a mad scientist. Directed by Leigh Whannell, the low-budget thriller was so successful that Universal rushed to adapt other titles from its classic monsters catalog, imagining a “Dark Universe” series that would update — and eventually connect — them all.

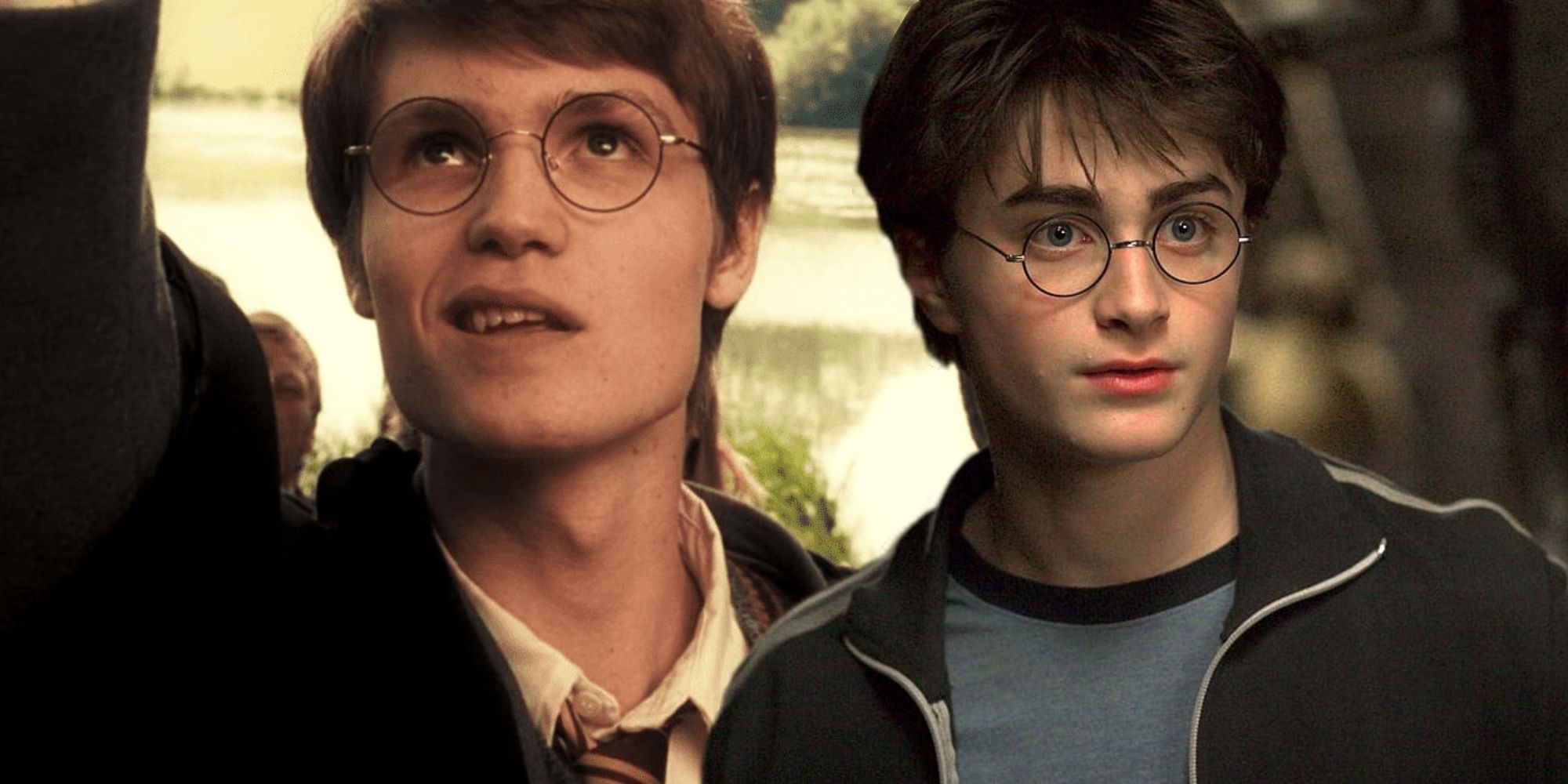

Somewhere along the way, the momentum stalled, and what had first been floated as a Ryan Gosling-led reinvention of “Wolf Man” now arrives in a slow, soulful and not especially scary form, starring Christopher Abbott in the title role. (Whannell stepped in to helm after Gosling and director Derek Cianfrance left the project.) In various ways, Abbott may actually be a more interesting candidate to play a man wrestling with his inner anger, as the actor — who has gravitated to tortured characters in such twisted projects as “James White,” “Piercing” and “Possessor” — conveys deep wells of rage behind his dark, brooding eyes.

As Blake Lovell in “Wolf Man,” Abbott is a decent guy and devoted dad, though he’s clearly worried about a temper that flares up from time to time. At one point, apologizing to his daughter, Ginger (Matilda Firth), for scaring her, he comes right out and says, “Sometimes when you’re a daddy, you’re so afraid of your kids getting scars that you become the thing that scars them.” It’s an astute line, well suited to a sensitive generation’s more self-aware approach to parenting. And yet, it so blatantly articulates the film’s Big Idea that it might have been nice to let audiences reach that conclusion on their own.

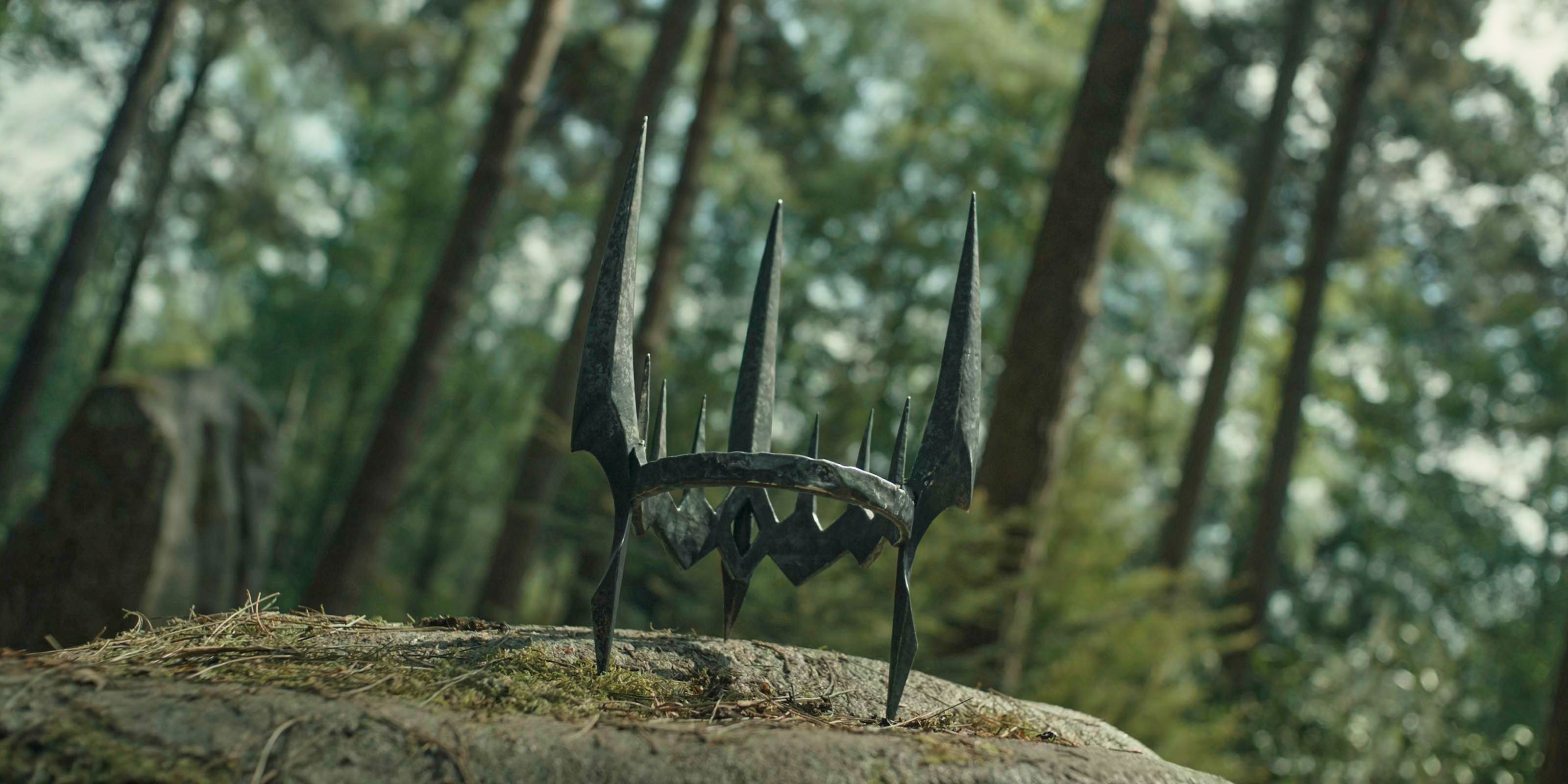

The screenplay, which bears the mark of both Whannell and “Insidious” writer Corbett Tuck, opens with a memory from Blake’s childhood three decades earlier. The boy (played by Zac Chandler, a good match for Abbott) was raised in a sylvan mountain farmhouse by a traumatically stern father, Grady (Sam Jaeger), who takes his son deer hunting in werewolf-infested woods. Grady lectures Blake on the fragility of life, teaching tough-love survival skills as a means of prolonging it. Viewers might reasonably expect those to come in handy later, though of course, Blake is the one destined to become the beast.

If anything, the initial takeaway is that Grady was too harsh, and Blake is determined to be a better dad, which explains his suggestion to relocate the beloved Lovells to his remote family home, where his wife, Charlotte (Julia Garner), is the one who must think quickly under pressure. That protective instinct is not an especially compelling hook for a big-studio horror movie (flawed characters tend to be more effective), but it does give the film a tragic dimension that connects it back to the iconic Universal classic.

In the 1941 original, Lon Chaney Jr. beautifully captured the agony of a man cursed, through no fault of his own, to be a danger to the one he loves. In both films, a selfless attempt to defend others results in the bite or scratch that turns a decent man into a monster, though the remake compresses that agony into a single night, as the full moon takes effect.

Both intellectually and emotionally, there’s something promising afoot, and yet, Whannell doesn’t go far enough. Whereas “The Invisible Man” grabbed audiences from the opening scene, using psychology to enhance the threat, the fate of the relatively thin “Wolf Man” feels obvious and preordained, as this model father grapples with a terrifying change that turns him against his family.

Whatever its strengths or weaknesses, every werewolf movie is ultimately judged by how well it handles the transformation and creature effects, and in that department, “Wolf Man” is a dud. Whannell opts to go the practical route, using prosthetics and other on-camera devices to simulate Blake’s agonizing mutation, but errs on the side of realism, with its infected father sweating up a storm before gnawing his arm with those sharp new canines of his.

Both Abbott and Garner are strong enough actors to have kept Blake’s emotional journey genuine, even if the film had embraced a more fantastical look. Instead, “Wolf Man” tries to put the audience in Blake’s place, even going so far as to shift perspectives between what Charlotte sees (her husband getting swollen and feverish) and Blake’s evolving POV. That eerie, almost infrared “wolf vision” — and the distorted audio that accompanies it — must have been tricky to pull off, but doesn’t add anything that Abbott’s performance doesn’t already convey. If anything, it lends the film a gimmicky and slightly retro quality.

Technically, “Wolf Man” operates in the opposite way from “The Invisible Man,” where any shot could conceivably include the eponymous psycho, leaving audiences to scan every frame for signs of him. Meanwhile, “Wolf Man” works best when its monsters are on-screen, and for this reason, the film’s assorted werewolves needed to appear more intimidating. That puts a heavy burden on sound designers P.K. Hooker and Will Files, whose intrusive mix of creepy noises is often indistinguishable from Benjamin Wallfisch’s discordant score.

In terms of scares, there aren’t many, and nearly all of them are given away by the film’s trailer. Rather than spoiling anything more, suffice to say that “Wolf Man” traps its three-person family unit in an isolated location, where a werewolf tries to huff and puff his way in, while one of their number mutates indoors. The battle between these two beasts is something to see, but the rest is too drawn out and inevitable, as Blake endures the sad fate of so many zombie movies: seeing a loved one turn dangerous before your eyes.

Trapped inside the feral character’s head, “Wolf Man” wants to say something — about the fear of inheriting aggression or mental illness from our parents, perhaps — but winds up making him pathetic in the process.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25623086/247270_Apple_watch_series_10_AKrales_0631.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·