![]()

In her seminal collection of essays, On Photography, Susan Sontag famously argued that “there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture.” She described the camera as a “sublimation of the gun,” a tool used to “violate” subjects, turning them into objects to be symbolically possessed.

This violence is baked into our language: we “take” pictures, we “shoot” subjects, we “capture” images.

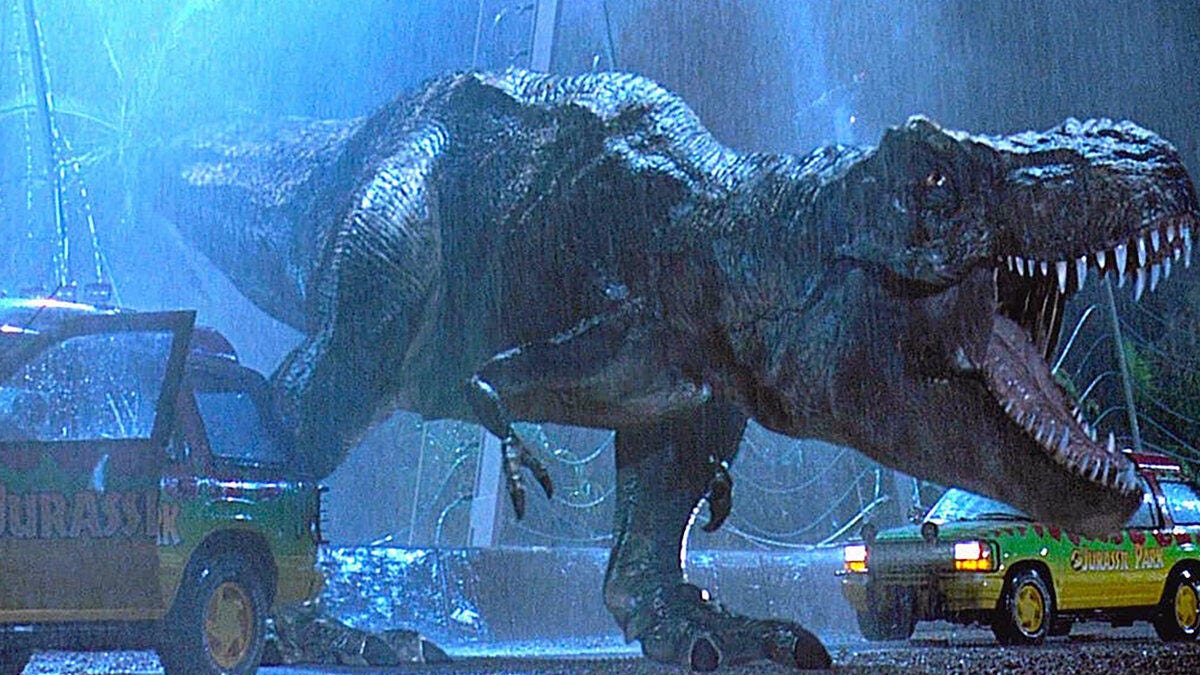

For decades, street photography has largely embraced this linguistic violence, a narrative built around domination and extraction. Many photographers view the art form as big-game hunting where the goal is to stalk a subject, take a shot, and mount the trophy on a wall. This “Hunter” mindset relies on three primary tactics: aggression, stealth, and satire.

We see aggression in the work of Bruce Gilden, who treats the sidewalk like a combat zone, using off-camera flash to stun pedestrians into a state of shock.

We see it in the frenetic sprints of Tatsuo Suzuki, whose subjects often recoil in terror, feeling cornered rather than seen. The result is a portrait of panic — a moment of visual terror that records a reaction without earning a relationship.

Then there is stealth. Mark Cohen, who produced his work without making eye contact, by shooting from the hip with a flash, capturing fragmented details of life in working-class Pennsylvania. Walker Evans, for all his genius, did the same thing in his famous subway portraits. Evans captured the era, but he did it by treating people like props. He hid a camera in his coat to steal images of exhausted, unexpecting commuters who were just trying to get home.

And then there is Martin Parr, who passed away at the end of 2025. Unlike Gilden’s physical confrontations, Parr was an intellectual hunter. His weapon was a sharp, merciless wit. He used a ring flash and saturated color to turn vacationgoers into caricatures of and for consumption.

His subjects were not assaulted physically, but they were flattened intellectually — reduced to pawns in a sardonic critique of class and cultural sensibility. He didn’t hunt images to reveal someone’s soul; he hunted for the punchline.

Hunters remain outside the circle of trust, poaching moments that do not belong to them.

Photography as Foraging

Foraging is a philosophy of patience, observation, and reception. It is not about aggressively extracting from the world, but about immersing oneself in an environment until it reveals a gift.

Foragers are purposeful wanderers who appreciate that the best things present themselves only when one is quiet, attentive, and present. Where the hunter seeks to take, the forager seeks to find what the environment offers.

Much like searching for wild mushrooms in a dense forest, you cannot force the prize to appear. You cannot command the street to produce a specific scene on demand. And, why would you want to? To expect a specific outcome is to blind oneself to the serendipitous, albeit elusive gifts the world offers.

Foragers reject the predator’s shortcuts, instead looking to those who transformed photography from a monologue into a dialogue and proved that the best work is given in trust, not taken by force.

Gordon Parks used his camera as a weapon against poverty, but he was armed with empathy. He waited—sometimes for weeks—without photographing at all, ensuring the communities he documented knew he was an advocate, not a tourist.

Look at Graciela Iturbide, specifically her work with the Zapotec women of Juchitán. She didn’t snipe from the bushes; she lived with the Zapotec until she became a comadre. Her iconic photos possess a mythic quality that a telephoto lens can never achieve, because the subjects are looking at her with recognition, not suspicion.

Susan Meiselas perfected the art of embedding with Carnival Strippers. A Hunter would have snuck into the tents, taken shots of naked bodies, and bolted. Meiselas stayed. She lived in the tents for three summers. “I didn’t want to just get the photos and run,” she said. “I wanted to know the women.” She didn’t just expose their likenesses; she recorded their voices, playing taped interviews alongside the prints so the subjects controlled their own story. As Magnum’s Kristen Lubben wrote, Meiselas turned the “unilateral act of taking” into a conversation.

The same held true in Nicaragua. Meiselas didn’t snipe the “Molotov Man” from the safety of a hotel balcony; she was in the trenches. She didn’t treat the revolution as content, but rather, as a relationship. She understood that: “The camera is an excuse to be someplace you otherwise don’t belong,” and the image is meaningless if you haven’t earned the right to stand there.

“As a photographer I don’t want to look at people as objects. I want to find other entry points to making photographs that bridge a relationship.” — Susan MeiselasThese artists embraced a fundamental paradox that the Hunter misses: To be invisible requires a loud crack of visibility.

True invisibility does not come from blinding people with your flash, relying on concealed cameras, hiding your intent, or “running and gunning.” It comes from consent. It requires the courage to announce your presence, to secure explicit or tacit approval, and to establish a connection rooted in empathy. Only when someone feels truly comfortable in your presence, when they can let down their guard and freely be themselves, can a photographer become truly invisible.

By rejecting the photographer-as-hunter analogy, subjects transform from “captures” into co-creators. This shift facilitates connection and engagement, which enables one to vanish into the moment and create art that resonates with intimacy, truth, and love.

By abandoning the hunt, we stop “taking” pictures of interesting things and start discovering photographs that are compositionally interesting, because they are emotionally true. You can snipe an image from the shadows with a telephoto lens, or you can earn a truth, face-to-face with consent.

The best photographs are never taken; they are received.

Foraging is hard. It demands time, restraint, and the humility to accept that most days will yield nothing at all. It requires showing up without guarantees, investing in people without knowing if an image will ever come to fruition, and choosing patience over spectacle.

Unlike the hunt, which rewards aggression with instant results, foraging asks the photographer to risk rejection and failure in service of something less predictable but far more enduring: not a reaction stolen in passing, but a moment shared, one that honors the subject’s humanity and elevates the work beyond shock into something rarer — something earned.

About the author: David M. M. Taffet is an award-winning photographer and a photographer for Mérida’s Dirección de Identidad y Cultura and Comité Permanente del Carnaval de Mérida. With a background in law, corporate restructuring, and building his own businesses, David has spent decades exploring the ethics of engagement while photographing in 54 countries. David advocates for ‘foraging’ over hunting to restore humanity to photography. You can view David’s work at www.invisibleman.photography and @invisiblemanphotography on Instagram.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·