This is Optimizer, a weekly newsletter sent every Friday from Verge senior reviewer Victoria Song that dissects and discusses the latest gizmos and potions that swear they’re going to change your life. Optimizer arrives in our subscribers’ inboxes at 10AM ET. Opt in for Optimizer here.

On TikTok, it’s disturbingly easy to find videos of influencers reconstituting vials of powdered peptides. In most, influencers hold up a vial of gray-market retatrutide, an unapproved weight loss drug colloquially known variously as GLP-3 (because it adds two extra agonists, glucagon and GIP), reta, and ratatouille. The other supplies on hand are alcohol swabs, syringes, and bacteriostatic water. These kitchen-counter chemists say how easy it is to turn a powdery substance in a bottle into a peptide that can be injected into the body. To figure out dosages, just use an online peptide calculator. The storage instructions are all over the place, but generally boil down to “keep it in your fridge for 30 to 90 days.”

Most tutorials don’t include simple, crucial instructions like “wash your hands” or “disinfect all surfaces.” The vast majority of influencers don’t wear latex gloves. The most anyone does is swipe an alcohol swab over the lids of the retatrutide and bacteriostatic water vials.

When I show these clips to a bona fide pharmacist and compounding specialist, her face falls.

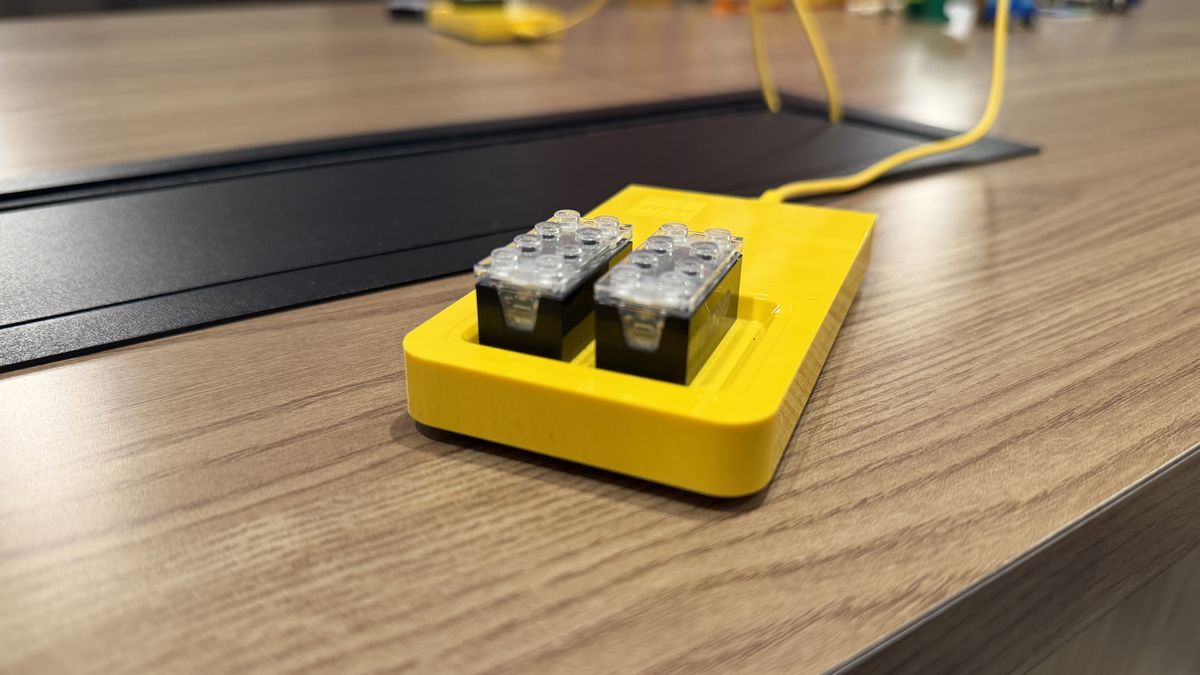

For the last month, I’ve been haunted by a vial of retatrutide in my freezer.

After researching so-called GLP-3s last month, I obtained a bottle through a TikTok influencer’s linktree. The problem with gray-market peptides is you don’t really know what you’re buying. Sites that sell these peptides — whether they’re GLP-1 or others — sometimes say their product is 99 percent pure and post an official-seeming certificate of authentication.

You want to make sure your vendor is the real deal, influencers say. Look for a third-party lab certification. That’s how you know it’s legit. For the vendors I use, the link is in my bio and use my code for a 10 percent discount.

My hypothesis is that my vial of dubiously sourced retatrutide — an unapproved drug that is still undergoing phase three clinical FDA trials — is not, in fact, retatrutide. At least, not the same thing that Eli Lilly is administering in its clinical trials. I figured I’d consult with a pharmacist, find a reputable third-party lab, send off my vial, and bada bing, bada boom, I’d have an answer.

As it turns out, it’s not that easy.

To understand why, we have to backtrack a bit. Normally, if you need a drug, you go through your doctor to get a prescription, and a pharmacy fills it. In 2022, there was a shortage of GLP-1 medications, which in turn led the FDA to allow compounding pharmacies to sell the drugs.

Compounding pharmacies create custom versions of drugs tailored to a specific patient when a commercial option isn’t viable. Say you’re allergic to an ingredient in the commercial version of a drug you need. Your doctor may direct you to a compounding pharmacy, which would re-create the drug and (generally) mix it for you. The market has exploded in recent years with GLP-1 medications like Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, and Zepbound. For many people, compounding pharmacies offered an affordable alternative to getting these medications when they could be helpful but weren’t available through the traditional route. If you weren’t a diabetic, for instance, but were struggling to lose weight due to hormonal conditions, you might not qualify under the stipulations put forth by your health insurance plan. In a Planet Money report, one user found their access denied after “improving too much” with the medication.

For those folks, compounded drugs were a godsend. Compounding pharmacies, however, aren’t the same thing as the gray market. The gray market consists of any wholesaler, distributor, or manufacturer that sells outside authorized distribution networks. Purchasing from the gray market often means reconstituting the drugs yourself, as TikTokers do. You can “do your homework,” as influencers urge, and still easily mix up what’s a legit compounding pharmacy that sources genuine active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) with certified testing and a license, and an unknown source that claims to be of similar makeup, quality, and potency.

“You can get an API from other places. It’s not like it’s only delivered to the Eli Lilly plant or wherever a drug is being made. But for something that’s not even FDA-approved yet, like retatrutide, it is only for research purposes,” explains Annie Lambert, a pharmacist and compounding specialist with Wolters Kluwer. “With the gray market, it should raise more questions, like ‘What is the quality? What is the safety? What is the purity? How would I know these things? How would I validate these things?’”

There’s always risk going for a compound medication, Lambert says. However, there’s far less risk going to a compounding pharmacy than to the gray market.

In our call, I show Lambert my dubious vial of retatrutide. The label claims 99 percent purity — but what does that actually mean in this context?

There’s a distinct difference between purity and potency, says Lambert. Potency refers to the active ingredient in the correct dosage. You’d expect a tablet of Tylenol to have about 325mg of the active ingredient in it, plus some other inactive components to help the drug bind together. There’s also a USP monograph — a written document that details and outlines quality standards. A monograph doesn’t exist for retatrutide, and the FDA has explicitly stated that retatrutide is not a component of any FDA-approved drug and is not included in the 503A Bulk Drug Substances list, which details all the bulk ingredients legitimate compounding pharmacies can use to create medications.

Purity, however, is a different story. Lambert says purity refers to the presence of endotoxins or exogenous materials in a drug that could cause harm.

“When you’re talking about injecting something into yourself, the bar is raised. There are some acceptable level of endotoxins. The allowable level is usually defined in a USP monograph. And if it’s not an approved product, then that standard is questionable too,” Lambert says.

So, even if I did send the vial off to a “reputable third-party lab,” when there’s no official monograph available to reference, it becomes a question of how and what a lab is testing for. As for the gray-market peptides, it’s impossible to say if you’re getting the real deal because the safe, tested, and “official” version of retatrutide doesn’t exist yet. Of the listings I’ve seen that claim to have third-party testing, most only address purity. But as Lambert said, with unapproved products, there’s no official agreed-upon standard for “purity.”

I still plan on sending this vial off for testing after more research and thought. But the big question is, what can any result even tell me?

While I’d love to say “Just don’t do it!” with regard to unapproved drugs, I’m well aware of the desperation when a drug that could help you feels arbitrarily withheld by red tape and cost. Just this week, my pharmacy called to tell me my insurer denied a medication I need and I must now jump through several bureaucratic hoops to obtain it. A broken healthcare system, insensitive doctors, and the stigma attached to larger bodies will make alternative sources of GLP-1 nigh impossible to resist for some people.

So I asked Lambert about the differences between how legitimate compounding pharmacies operate versus the gray market, and how to spot the difference.

According to Lambert, legitimate compounding pharmacies will have testing and verification for raw ingredients or APIs. Once a drug is compounded, there’s also sterility and endotoxin testing, among others, to ensure that the medication lasts for the amount of time listed in instructions and packaging. (Most gray-market certificates of authentication I’ve reviewed only list purity — not these other factors.) Additionally, these standards and processes are enforced by state boards of pharmacy, accreditation bodies, and the FDA itself.

“As a patient, you should be able to always ask, ‘What pharmacy is this coming from?’” Lambert says. For example, if you go through a service like Ro for GLP-1s or other drugs, those companies are sourcing from a smaller compounding pharmacy — they don’t manufacture it themselves. It’s on consumers to ensure that the pharmacy sending the drug is licensed in the state they live in. That pharmacy should also be able to provide sterile compounding designations or endorsements. You should also ask pharmacies where they source APIs and for third-party certificate of analysis for each lot number. While third-party testing isn’t required for compounding pharmacies, it’s a good question to ask if you feel something isn’t quite right.

Other smart questions include:

- Does the pharmacy follow USP 797 standards for sterilization?

- What training or certifications do the compounding staff have?

- Who can you call or contact if there are concerns or questions?

If you’re potentially looking at sourcing GLP-1s or retatrutide from a med spa, nurse practitioner, or other wellness institution, it’s doubly important to ask where they are sourcing from. If they don’t name a valid pharmacy, you may be inadvertently obtaining gray-market peptides.

My vial of “retatrutide” only came with a vial of bacteriostatic water. There were no instructions for reconstitution, no extra materials like syringes, and no storage instructions. When I bought it, I could swear it was sold with a link to a “lab certification” and lot number to verify purity. As of this writing, the seller’s product listing has no such certificates available. There is, however, a note that it will last 56 days refrigerated once reconstituted, and up to a year in powdered form. (A year from when is unclear.)

I have no plans to actually reconstitute this vial. But if I did, I’d want to find better tutorials than the ones I’ve found on TikTok. As Lambert explains, compounding pharmacists do much more in lab settings when formulating drugs.

“At bare minimum, per USP standards, when we compound in immediate pharmacy or healthcare settings, I’m going to at least wash my hands, disinfect the counter, disinfect the top of the lid, and you want everything to be as clean as possible,” she says.

“But maybe the first question to ask is: ‘How much risk am I willing to take?’”

Photography by Victoria Song / The Verge

Follow topics and authors from this story to see more like this in your personalized homepage feed and to receive email updates.

8 hours ago

20

8 hours ago

20

English (US) ·

English (US) ·