Diagrams from Thomas Young's 1807 Lectures bear striking resemblance to abstract figures in af Klint's work.

Hilma af Klint's Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 17, 1915. Credit: Hilma af Klimt Foundation

In 2019, astronomer Britt Lundgren of the University of North Carolina Asheville visited the Guggenheim Museum in New York City to take in an exhibit of the works of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint. Lundgren noted a striking similarity between the abstract geometric shapes in af Klint's work and scientific diagrams in 19th century physicist Thomas Young's Lectures (1807). So began a four-year journey starting at the intersection of science and art that has culminated in a forthcoming paper in the journal Leonardo, making the case for the connection.

Af Klint was formally trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and initially focused on drawing, portraits, botanical drawings, and landscapes from her Stockholm studio after graduating with honors. This provided her with income, but her true life's work drew on af Klint's interest in spiritualism and mysticism. She was one of "The Five," a group of Swedish women artists who shared those interests. They regularly organized seances and were admirers of theosophical teachings of the time.

It was through her work with The Five that af Klint began experimenting with automatic drawing, driving her to invent her own geometric visual language to conceptualize the invisible forces she believed influenced our world. She painted her first abstract series in 1906 at age 44. Yet she rarely exhibited this work because she believed the art world at the time wasn't ready to appreciate it. Her will requested that the paintings stay hidden for at least 20 years after her death.

Even after the boxes containing her 1,200-plus abstract paintings were opened, their significance was not fully appreciated at first. The Moderna Museum in Stockholm actually declined to accept them as a gift, although it now maintains a dedicated space to her work. It wasn't until art historian Ake Fant presented af Klint's work at a Helsinki conference that the art world finally took notice. The Guggenheim's exhibit was af Klint's American debut. "The exhibit seemed to realize af Klint's documented dream of introducing her paintings to the world from inside a towering spiral temple and it was met roundly with acclaim, breaking all attendance records for the museum," Lundgren wrote in her paper.

A pandemic project

Lundgren is the first person in her family to become a scientist; her mother studied art history, and her father is a photographer and a carpenter. But she always enjoyed art because of that home environment, and her Swedish heritage made af Klint an obvious artist of interest. It wasn't until the year after she visited the Guggenheim exhibit, as she was updating her lectures for an astrophysics course, that Lundgren decided to investigate the striking similarities between Young's diagrams and af Klint's geometric paintings—in particular those series completed between 1914 and 1916. It proved to be the perfect research project during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Lundgren acknowledges the inherent skepticism such an approach by an outsider might engender among the art community and is sympathetic, given that physics and astronomy both have their share of cranks. "As a professional scientist, I have in the past received handwritten letters about why Einstein is wrong," she told Ars. "I didn't want to be that person."

That's why her very first research step was to contact art professors at her institution to get their expert opinions on her insight. They were encouraging, so she dug in a little deeper, reading every book about af Klint she could get her hands on. She found no evidence that any art historians had made this connection before, which gave her the confidence to turn her work into a publishable paper.

The paper didn't find a home right away, however; the usual art history journals rejected it, partly because Lundgren was an outsider with little expertise in that field. She needed someone more established to vouch for her. Enter Linda Dalrymple Henderson of the University of Texas at Austin, who has written extensively about scientific influences on abstract art, including that of af Klint. Henderson helped Lundgren refine the paper, encouraged her to submit it to Leonardo, and "it came back with the best review I've ever received, even inside astronomy," said Lundgren.

Making the case

Young and af Klint were not contemporaries; Young died in 1829, and af Klint was born in 1862. Nor are there any specific references to Young or his work in the academic literature examining the sources known to have influenced the Swedish painter's work. Yet af Klint had a well-documented interest in science, spanning everything from evolution and botany to color theory and physics. While those influences tended to be scientists who were her contemporaries, Lundgren points out that the artist's personal library included a copy of an 1823 astronomy book.

Excerpt from Plate XXIX of Young's Lectures Niels Bohr Library and Archives/AIP

Af Klint was also commissioned to paint a portrait of Swedish physicist Knut Angstrom in 1910 at Uppsala University, whose library includes a copy of Young's Lectures. So it's entirely possible that af Klint had access to the astronomy and physics of the previous century and would likely have been particularly intrigued by discoveries involving "invisible light" (electromagnetism, x-rays, radioactivity, etc.).

Young's Lectures contain a speculative passage about the existence of a universal ether (since disproven), a concept that fascinated both scientists and those (like af Klint) with certain occult interests in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In fact, Young's passage was included in a popular 1875 spiritualist text, Unseen Universe by P.G. Tait and Balfour Stewart, that was heavily cited by Theosophical Society founder Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Blavatsky in turn is known to have influenced af Klint around the time the artist created The Swan, The Dove, and Altarpieces series.

Lundgren found that "in several instances, the captions accompanying Young's color figures [in the Lectures] even seem to decode elements of af Klint's paintings or bring attention to details that might otherwise be overlooked." For instance, the caption for Young's Plate XXIX describes the "oblique stripes of color" that appear when candlelight is viewed through a prism that "almost interchangeably describes features in af Klint's Group X., No. 1, Altarpiece," she wrote

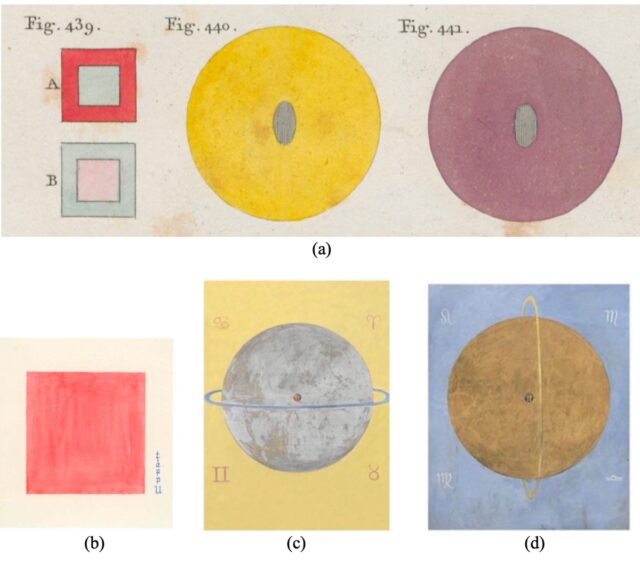

(a) Excerpt from Young's Plate XXX. (b) af Klint, Parsifal Series No. 68. (c and d) af Klint, Group IX/UW, The Dove, No. 12 and No. 13. Credit: Niels Bohr Library/Hilma af Klint Foundation

Art historians had previously speculated about af Klint's interest in color theory, as reflected in the annotated watercolor squares featured in her Parsifal Series (1916). Lundgren argues that those squares resemble Fig. 439 in the color plates of Young's Lectures, demonstrating the inversion of color in human vision. Those diagrams also "appear almost like crude sketches of af Klint's The Dove, Nos. 12 and 13," Lundgren wrote. "Paired side by side, these paintings can produce the same visual effects described by Young, with even the same color palette."

The geometric imagery of af Klint's The Swan series is similar to Young's illustrations of the production and perception of colors, while "black and white diagrams depicting the propagation of light through combinations of lenses and refractive surfaces, included in Young's Lectures On the Theory of Optics, bear a particularly strong geometric resemblance to The Swan paintings No. 12 and No.13," Lundgren wrote. Other pieces in The Swan series may have been inspired by engravings in Young's Lectures.

This is admittedly circumstantial evidence and Lundgren acknowledges as much. "Not being able to prove it is intriguing and frustrating at the same time," she said. She continues to receive additional leads, most recently from an af Klint relative on the board of the Moderna Museum. Once again, the evidence wasn't direct, but it seems af Klint would have attended certain local lecture circuits about science, while several members of the Theosophy Society were familiar with modern physics and Young's earlier work. "But none of these are nails in the coffin that really proved she had access to Young's book," said Lundgren.

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·