AMD Phenom II X3 Black Edition

Choose wisely! The correct answer, the explanation, and an intriguing story await.

Correct Answer: AMD K7 Athlon / Duron

A brief explanation why

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, AMD Athlon processors, particularly those based on the Thunderbird core, gained widespread attention not only for their performance but also for an unusual and enthusiast-friendly quirk: they could be "unlocked" with nothing more than a pencil.

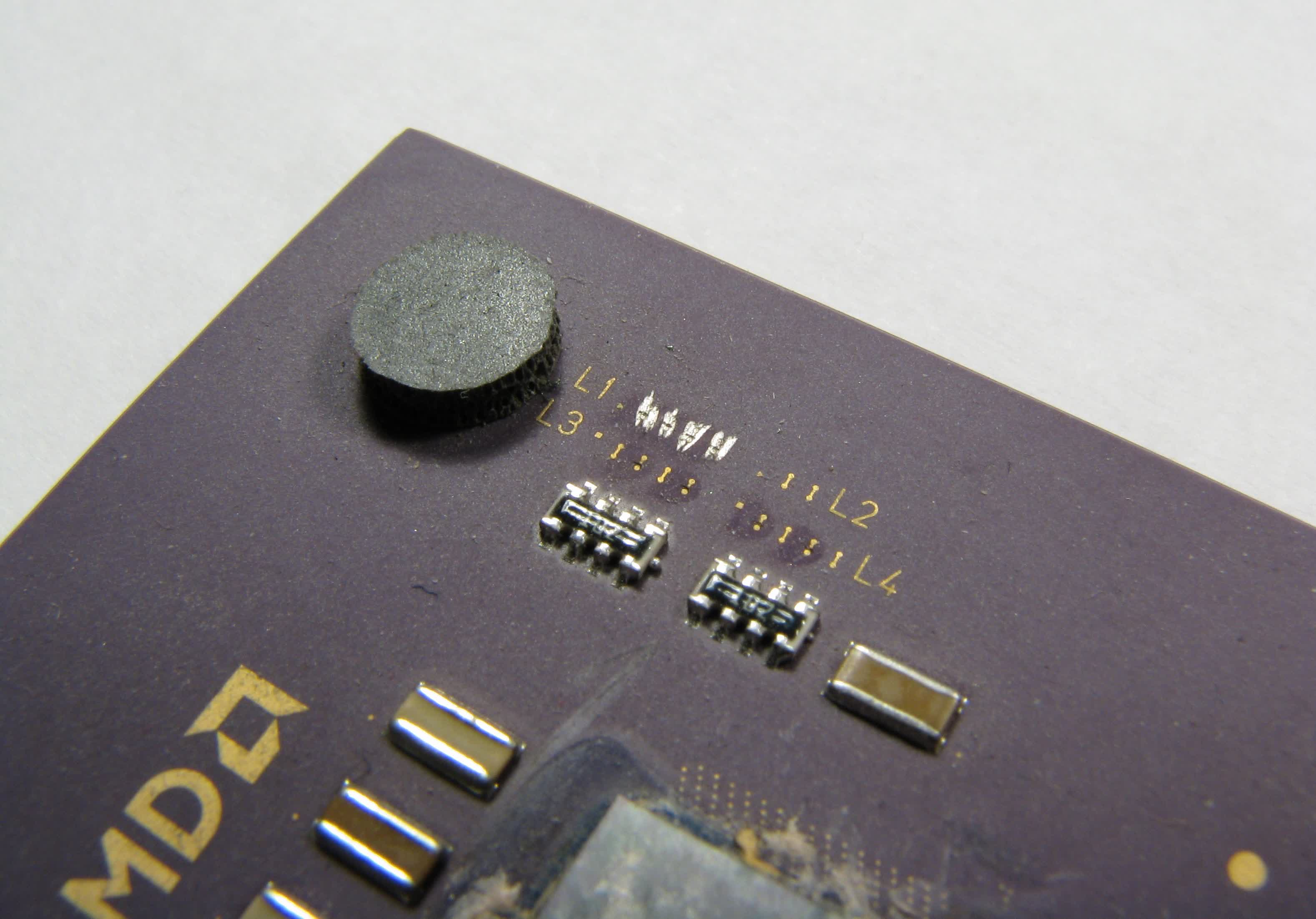

These CPUs, which initially came in the Slot-A format and later in Socket A (Socket 462), were among AMD's first to feature multiplier locking. To enforce the lock, AMD used lasers to sever the tiny copper connections on the processor's surface known as the L1 bridges. This move was partly a response to unscrupulous computer vendors who would overclock lower-end chips, remark them as higher-end models, and sell them at inflated prices.

Fun fact: The "pencil trick" involved drawing over tiny laser-cut L1 bridges with graphite to re-enable locked multipliers on early 2000s AMD CPUs.

But of course, it wasn't long before enterprising enthusiasts discovered a workaround. By simply using the graphite from a #2 pencil – an inexpensive and accessible conductor – users could reconnect the L1 bridges on Thunderbird-based Athlon CPUs. This effectively restored access to the chip's clock multiplier settings in the system BIOS, completing factory-destroyed circuits and allowing users to tweak CPU speeds far beyond factory specifications.

This DIY hack became widely known as the "pencil trick."

The trick was especially popular because it allowed significant overclocking gains with minimal investment. At a time when Intel was locking down its processors more aggressively, AMD's more tweakable chips helped solidify its reputation among performance enthusiasts and budget-conscious gamers.

Later revisions of the Athlon line, particularly as AMD transitioned from ceramic to organic PCB packaging (such as in the Palomino core used in Athlon XP CPUs), made the unlocking process more difficult. The laser cuts created deeper pits in the L1 bridges that couldn't be reliably bridged with just graphite. Instead, conductive ink, silver lacquer, or special unlocking kits were needed to fill the gaps and restore functionality.

As our server guru Per Hansson explained in a guide at the time, successfully bridging these newer CPUs required more care, precision, and better materials than the original pencil method allowed.

Nonetheless, the pencil trick remains one of the most iconic examples of low-tech ingenuity in the history of PC hardware tweaking, and a testament to the creativity of early overclockers.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·