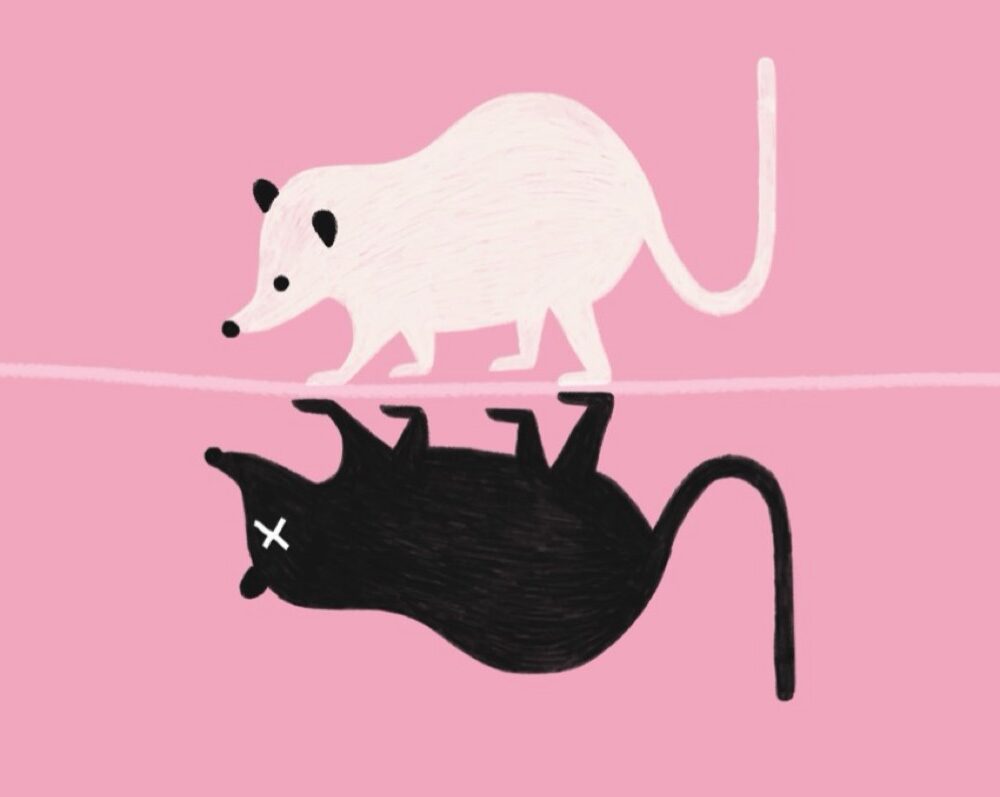

oh death, where is thy sting

Susana Monsó chats with Ars about her new book, Playing Possum: How Animals Understand Death.

Credit: Princeton University Press

Human beings live every day with the understanding of our own mortality, but do animals have any concept of death? It's a question that has long intrigued scientists, fueled by reports of ants, for example, appearing to attend their own"funerals"; chimps gathering somberly around fallen comrades; or a mother whale who carried her dead baby with her for two weeks in an apparent show of grief.

Philosopher Susana Monsó is a leading expert on animal cognition, behavior and ethics at the National Distance Education University (UNED) in Madrid, Spain. She became interested in the topic of how animals experience death several years ago while applying for a grant and noted that there were a number of field reports on how different animal species reacted to death. It's an emerging research field called comparative thanatology, which focuses on how animals react to the dead or dying, the physiological mechanisms that underlie such reactions, and what we can learn from those behaviors about animal minds.

"I could see that there was a new discipline that was emerging that was very much in need of a philosophical approach to help it clarify its main concepts," she told Ars. "And personally, I was turning 30 at the time and became a little bit obsessed with death. So I wanted to think a lot about death and maybe come to fear it less through philosophical reflection on it."

Her years of research turned into a book, now translated into English: Playing Possum: How Animals Understand Death (Princeton University Press). In thoughtful prose peppered with lively anecdotes, Monsó tackles our all-too-human anthropocentric biases surrounding death and deftly outlines a useful philosophical framework for understanding animal cognition to illustrate how a minimal concept of death might be possible, even if it differs among species. She argues that far from being an exclusively human attribute, a concept of death is actually quite widespread throughout the animal kingdom.

"We're not the only animal who understands death, nor are we the only one who grieves, nor the only one who kills on purpose or for fun," she writes. "Scientists have been trying for a long time to find a characteristic that will definitively separate us from the other species. So far all candidates have fallen. Neither the use of tools, nor culture, morality, or rationality are exclusive of human beings. Nor is the concept of death."

Ars chatted with Monsó to learn more.

Ars Technica: As a relatively new discipline, you believe that comparative thanatology needs philosophy. Can you tell us more about what philosophy brings to the table?

Susana Monsó: I think philosophy is very helpful to science in general. You have to do philosophy if you do science because you have to make philosophical choices whenever you decide on which topics you're going to focus on, what sort of questions you're going to be asking, what kind of methodology you're going to be using, how you're going to be analyzing the results, how you're going to interpret those results. All of these are philosophical choices. So science already has philosophy within it.

But sometimes the approach of a philosopher is needed. Philosophers are trained in conceptual analysis. Most scientists are aware of the importance of conceptual characterizations or definitions, but very often they think that so long as they provide a definition and the definition is clearly set out in the paper, that's all they need to do. As long as we're all clear on how we're using the terms, that's everything.

I think that's wrong because not all definitions are equal. Not all characterizations are equal, and how you characterize your terms is going to determine so much of what comes afterward. So I think philosophy has the capacity to analyze concepts and determine how best to characterize them. Philosophers have an advantage because we don't have to do empirical research, which requires a very narrow focus. You can't take on a super big question if you're doing an experiment, it has to be a small question. Sometimes scientists lose sight of the bigger picture. Philosophy has the advantage of being able to look at things from a wider perspective and reflect on how different questions relate to each other, how different fields are connected, and so on.

Virginia opossum feigning death, or "playing possum." Credit: John Ruble /Public domain

Ars Technica: You've said that one benefit to a more philosophical approach is that it can help overcome certain biases.

Susana Monsó: Amongst comparative psychologists in general and also field biologists, there's this fear of anthropomorphizing animals. It's a very reasonable thing to fear because we do have a tendency to project our own feelings, our own thoughts, onto even computers and Roombas. But I feel that scientists are not so often reflecting on other biases that can affect their research that are also important. There are already all these safeguards against anthropomorphism, so I wanted to focus on another bias in my book: anthropocentrism, which is the idea of taking the human way of life or the human mind as the measure of all things.

In particular, I identify two manifestations of anthropocentrism that permeate comparative thanatology: emotional anthropocentrism and intellectual anthropocentrism, the tendency of thanatologists to think that the only way of understanding death is the human way. So animals either have our concept of death or none at all. That's intellectual anthropocentrism. The idea that the only interesting emotional reactions to death are human-like reactions, that's emotional anthropocentrism—a focus on grief as a response to death.

With regards to intellectual anthropocentrism, if we're looking for a human-like concept of death in animals, it's just much less interesting, because we have our language and rituals and cultural manifestations and symbolism surrounding death, all of which can support a very complex concept of death. Non-linguistic animals are going to lack this; they're not going to have a concept of death that is as complex as ours. I'm more interested in whether they have anything that counts as a concept of death. For that, I think we need to begin with what I call the minimal concept of death and build from there. With regard to emotional anthropocentrism, if we just focus on grief, we're going to miss out on so much more that might be shaping animals' understanding of death.

Ars Technica: Your definition of a minimal concept of death is one that provides variability at the species level as well as variability at the individual level. Why is that important?

Susana Monsó: You have to strike a balance between finding something that can accommodate variability across species and also within species. But that can also allow us to have something that is still recognizably a concept of death. Sometimes philosophers will start peeling off layers until what's left is something that's not really what we were talking about at the beginning. I wanted to find a middle ground, and I think the minimal concept of death, as I conceive it, allows for this. It can accommodate all these species' variability but also understands that dead individuals don't do things, and this is a permanent state. It's still recognizably a concept of death.

2011 footage of chimpanzees apparently mourning the deaths of a nine-year-old male and infant.

Ars Technica: You write that the holy trinity of a concept of death is cognition, experience, and emotion. How does that fit within your framework?

Susana Monsó: This holy trinity idea comes from my work with Antonio Osuna Mascaró. It came from us reflecting on what has to happen for an animal to develop a concept of death. The minimal concept of death is just a theoretical construct that lets you determine that an animal indeed has some understanding of death, but it doesn't tell you how this is going to appear in the world. So the holy trinity gives us the empirical preconditions that need to be in place for an animal to develop a concept of death.

What I like about this idea is that, again, it allows for variability because we believe that you need a certain minimal level of these three factors, but at the same time, high levels of one can compensate for relatively low levels of another. So if you have, for instance, a very smart individual, she might not need a lot of experiences with death in order to learn about it. Or an animal who has many, many, many experiences with death might not need to be too smart in order to acquire a concept of death and so on.

Ars Technica: Many species of animals have a minimal concept of death, but can they conceive of their own mortality? Do they need a theory of mind? That's a big part of what makes us human.

Susana Monsó: Exactly. I think that our awareness of our own mortality is something that's sustained by narratives. You don't really have any strong evidence that you yourself are going to die. You don't really have any proof of that. You just believe it because you've been told we're all going to die. So animals, they don't have this help in their development of a concept of death. They have to do it solipsistically. And here I'm assuming that animal communication cannot sustain communication about death. But of course, we don't know that for sure.

Assuming that's the case, then each animal has to confront this question on their own and start gathering experience that can allow them to make inductive generalizations based on it. If I see enough individuals of my species die, then I can start generalizing towards the future: "Oh, all of these individuals died because they came across a leopard. So if other animals come across a leopard, they might also die." Eventually that animal might also think about that as applying to herself: "That might also happen to me if I come across a leopard." It's more difficult because it requires the animal to have a shift in attention and to bring herself into focus and adopt an external perspective on herself. It's going to require more cognitive sophistication.

I don't think a theory of mind has to necessarily be there because I think an animal could potentially conceive of her personal mortality on a lower level of understanding: "Well, I'm not going to be able to do things. My body is just going to stop working or not be able to do things." So I don't think necessarily she's going to have to reflect on her own cognition.

As I emphasize in the book, a theory of mind is only going to be a part of what an animal understands to end with death—if the animal indeed has a theory of mind. I'm inclined to believe that a theory of mind is a very specifically weird way of understanding humans and maybe some animals. I'm not so inclined to think that other animals are going to conceive of other psychology in this kind of way. They might just think of others as bodies or as bodies that behave in a certain way. I don't think that's a problem because in the end, what you understand to end with death, it is just going to mirror how you understand living beings.

Ars Technica: I was intrigued by your descriptions of grieving behavior in some animals, or at least what we interpret as grieving behavior. You emphasize that it's not a binary, it's a spectrum.

Susana Monsó: Exactly. The minimal concept of death is just a theoretical construct that is meant to indicate when an animal has some understanding of death. But many animals are going to start off already with a bit of a higher level because they're going to have the capacity to associate an irreversible loss of functionality with certain causes, and maybe generalize beyond the here and now. Or they might attach certain emotional qualities to it. For instance, for a predator or a vulture, death might be something that they conceive as something good, as a gain, as something positive for them. Whereas for a gorilla, who's a vegetarian, death might be something that they associate with losing a companion, so being hurt. Animals can diverge and they can have different paths in the way they learn about death and how they ultimately conceive it.

Ars Technica: Everyone likes to bring up the famous 2018 case of the whale that carried her dead baby with her for 17 days. You mentioned that this might just be part of the ingrained maternal response. It's not necessarily grieving as humans might interpret it.

Susana Monsó: In the book, I emphasize very strongly that the question of whether animals can grieve is a different question than whether they can understand death. So often they are confused with each other. I even came across a scientific paper where the authors were saying, "Well, we don't know if these apes understand death because we don't have any indication that they understand the emotional importance of it." That's a different question. I think a lot of the focus has been on grief, which I think is positive because animal grief is a pressing issue—it is a very important side effect of a lot of our practices towards animals. We tend to not think about these issues as much as we should.

The orca Tahlequah made headlines when she carried her dead baby for 17 days and 1,000 miles in 2018—dubbed a "tour of grief." Credit: Ken Balcomb/Center for Whale Research

It's just that if we only focus on this, we're potentially missing many other ways in which animals might relate to death that don't necessarily have to do with losing a loved one, which is what grief is. Grief is an emotional reaction caused by the loss of a loved one specifically. It's a side effect of love, so to speak. It need not tell us much about the animal's smarts. What it's telling us is the animal was very, very emotionally attached to someone that she lost.

Some people say, "Well, maybe these primate mothers who carry their dead infants don't realize that their infant is dead." I think there are a lot of reasons why this is implausible, but it just doesn't follow from the fact that you understood that the baby is dead, that you're going to want to let go of it. It might precisely make you want to not let go of it because you are suffering on account of this reality that you have comprehended.

Ars Technica: You tell the story of a woman who gave birth to a stillborn child who didn't want to leave it for a while. It was part of her process.

Susana Monsó: Exactly. It's really heartbreaking. The article was published in Aeon, and the author is a neuroscientist at Oxford. She's not someone about whom we could say, "Well, she's just not grasping that her baby is dead." Of course, she perfectly understood what was happening, but yet still she wanted to take care of that baby for a couple of days. She was really torn because, rationally, she understood that the baby was dead, but also emotionally, she just didn't want to let go. She felt it as something very animal, very ancient in her that probably has its roots in the fact that humans are K-strategists, that maternal care is absolutely crucial for the survival of our offspring. These mechanisms are not just going to be switched off as soon as the baby dies. It's a much more difficult process for it to happen.

Ars Technica: A recurrent theme in your book is that humans try to identify things that are uniquely human and thus make us special and unique. Your point is that if we come to terms with the fact that we're animals, we may also reconcile with our own mortality.

Susana Monsó: I think it is that way for a lot of people. I'm also very interested in the question itself. But this whole project was partially motivated at an unconscious level by a deep need in me to understand death and to understand myself as a mortal being. For me, this whole journey has enabled me to come to terms with my mortality, because it has helped me to see that this is part of the rules of the game. We're just another animal, and if you want to be alive, you have to die. That's just how it is. Paying more attention to animals is so beneficial on so many levels. It brings us much more humility. Part of what it does is allow us to realize that we're mortal beings just as they all are, because we are animals. We're bodies at work but they can't work forever. It's not a tragedy, it's just a fact of life.

Jennifer is a senior reporter at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25467512/codblackops6.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2021/07/06/971/n/1922153/7d765d9b60e4d6de38e888.19462749_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/29/957/n/1922441/c62aba6367215ab0493352.74567072_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/29/987/n/49351082/3e0e51c1672164bfe300c1.01385001_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/30/711/n/1922441/c62313206722590ade53c4.47456265_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·