Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

The big picture: Numerous mysteries remain regarding black holes, with astronomers particularly interested in the formation of the oldest black holes in the early universe. Recent observations from the James Webb Space Telescope could shed light on how supermassive black holes began forming so quickly after the Big Bang.

A recently published study describes an ancient black hole that eats matter far faster than previously thought possible. The discovery could offer a clue as to how supermassive black holes formed in the early universe.

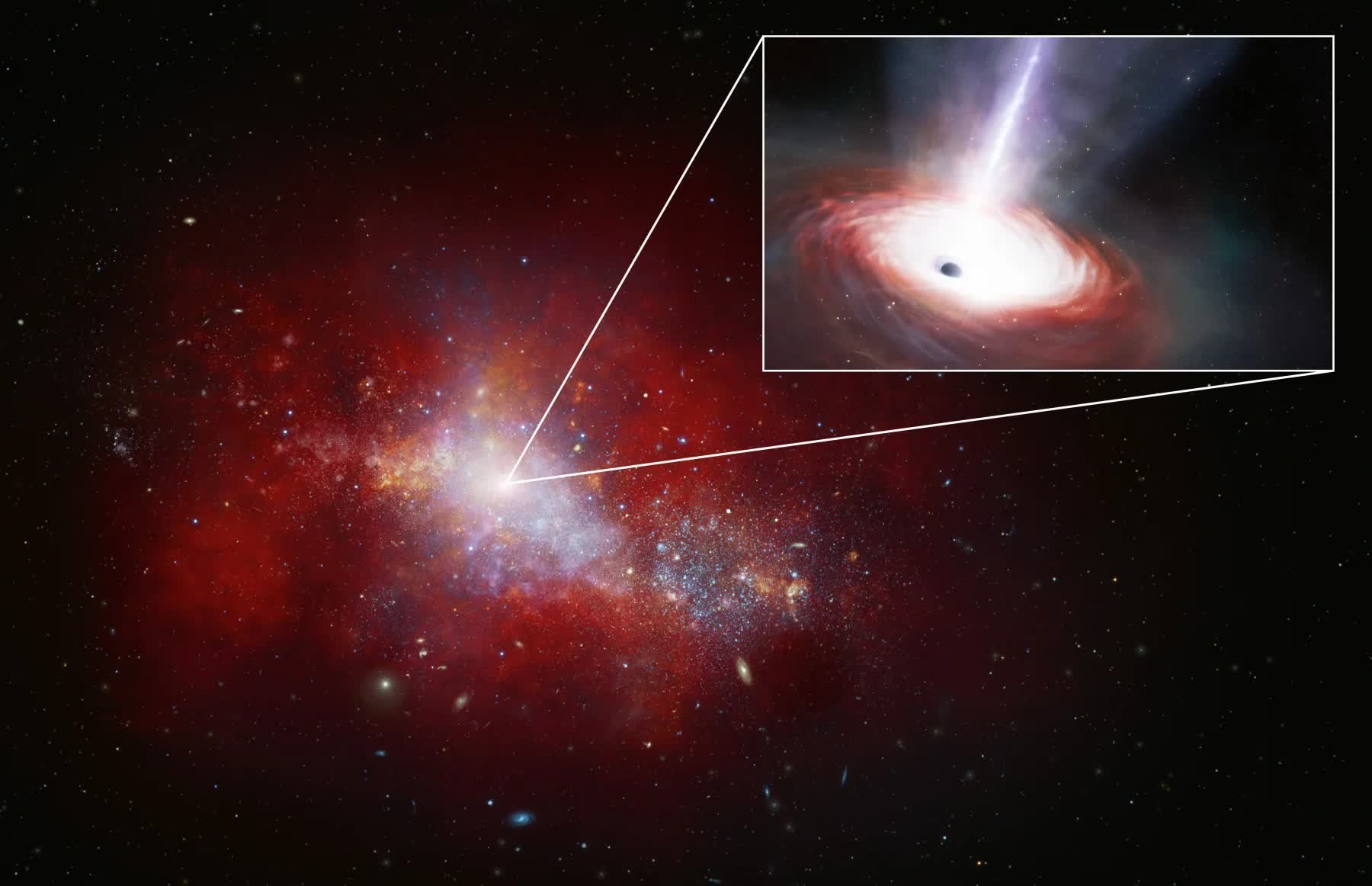

The black hole, labeled LID-568, was discovered using the James Webb Telescope and data from the Chandra-COSMOS Legacy Survey. At about 7.2 million times the Sun's mass, it's considered a relatively low-mass black hole.

Artist's impression. Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/M. Zamani

However, it is extremely active and bright in X-ray scans compared to other black holes of its age. Because of the time it takes for light from the distant cosmos to reach Earth, astronomers observe it as it appeared about 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, which occurred roughly 13.8 billion years ago.

Analysis of LID-568's radiation output indicates it is absorbing matter at around 40 times its Eddington limit – the theoretical boundary at which a black hole's inward gravitational force balances out the heat emitted by the material it consumes. Astronomers previously believed that supermassive black holes couldn't form so soon after the Big Bang, but super-Eddington black holes might offer one explanation for their presence so early in the universe's history.

Researchers believe LID-568 likely gained much of its mass during a single rapid gorging event. One of two things might have fueled it: light seeds – smaller black holes formed from the corpses of the universe's earliest stars – or heavy seeds, which involve the direct accumulation and collapse of gas and dust.

Understanding how black holes quickly grew supermassive after the Big Bang could help explain the formation of galaxies in the early universe, many of which have a supermassive black hole at their center. One example, JADES-GS-z14-0, surprised astronomers when the James Webb telescope detected it earlier this year.

It displayed surprisingly active and mature star formation only around 300 million years after the Big Bang. Researchers previously doubted that galaxies could grow so large in the first few hundred million years of the universe's history, but JADES-GS-z14-0 and other recently spotted objects are challenging prior notions.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25715695/VST_1105_SIte.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/11/04/810/n/1922564/da875c20672911f51e8a59.58915976_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·