Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

Editor's take: If TSMC raises its prices as high as we are hearing they intend, then many companies will have no choice but to step off the curve of Moore's Law. Maybe having an alternative like Intel is not such a bad idea.

In recent weeks we've been hearing about some of the proposed price increases coming for TSMC's N2 process starting next year. We have been thinking through the implications of this since then, and in light of the developments at Intel, we believe their significance has become even more relevant.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

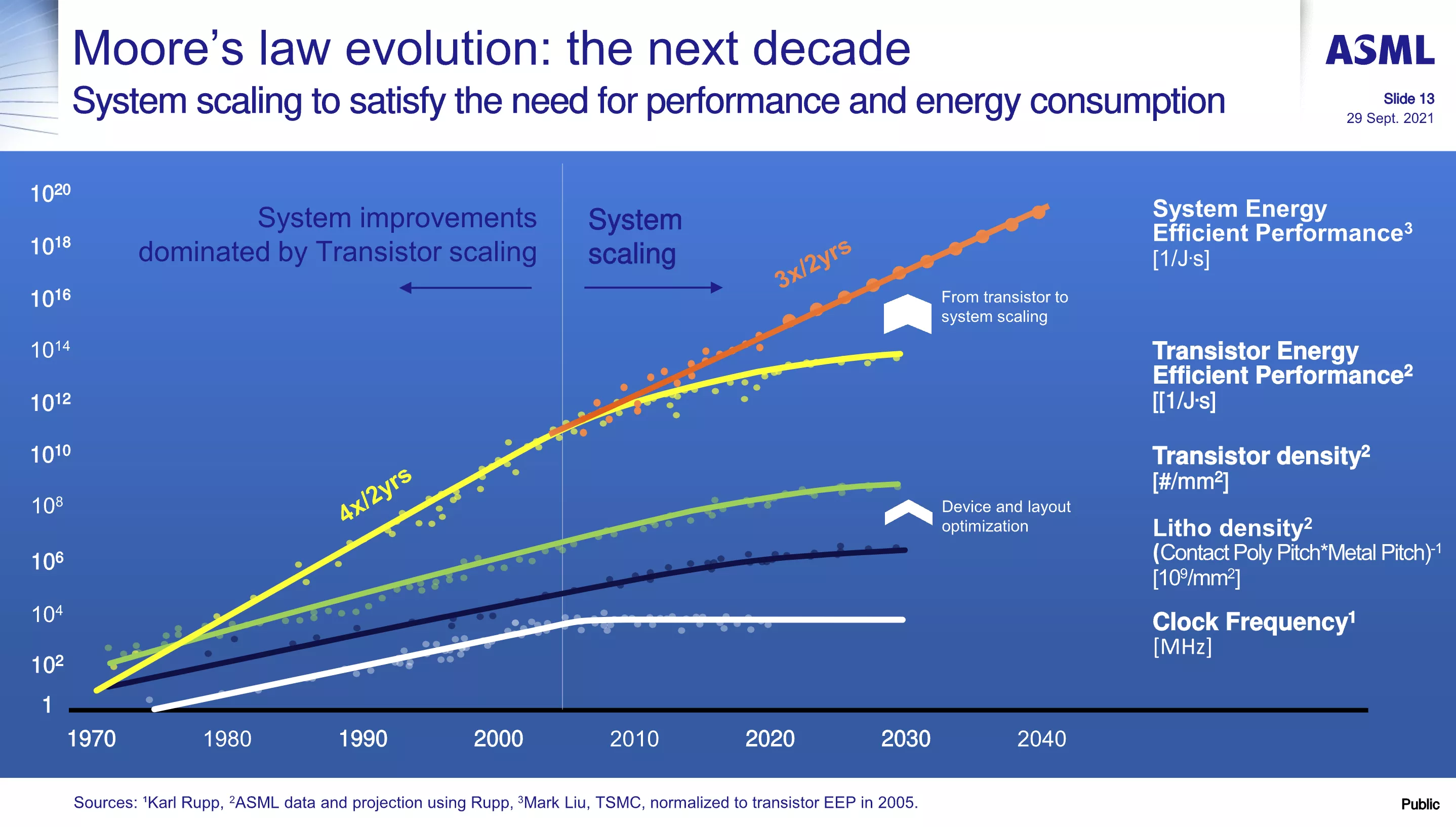

Put simply, in the absence of viable competition, TSMC transitions from being an 'effective' leading-edge monopolist to a true monopolist. This allows them to raise prices as high as they want. Work through the math on that, and it quickly becomes apparent that many companies designing chips at the leading edge today will have to step off the Moore's Law curve because it is no longer economically viable.

Of course, TSMC is not going to raise prices to infinity and cut off all demand, but they will price to maximize their own value extraction. This will likely lead to a much smaller pool of customers who can afford to design chips at the leading edge.

Source: Lei Mao's Log Book

Let's use an example. Imagine a sizable TSMC customer – not in the Top 3, but maybe in the Top 10. They likely pay TSMC $20,000 per wafer today, with lower-volume customers paying closer to $25,000. Let's say this company has a chip that is 170 mm². Using the handy Semi-Analysis Die Yield Calculator, that works out to 325 chips per wafer, or $61 per chip. If the company prices the chip at $140, they achieve gross margins of 55%, which is good but not great.

Now suppose TSMC raises its price to $40,000 for the next process. Estimates for density improvements for N2 are still coming in, but let's assume a 15% increase in die per wafer (375 KGD). The cost per chip, however, jumps to $107. This illustrates the heart of the Moore's Law slowdown – density increases now greatly lag price increases. If the design company cannot pass on cost increases to customers and remains stuck at a $140 price point, gross margins drop to 22%, which is unsustainable.

Now suppose TSMC raises its price to this customer to $40,000 for its next process. Estimates for density improvements for N2 are still coming in, but let's assume we get 15% more die per wafer (375 KGD), but the cost is now $107 per chip. This is the heart of the Moore's Law slowdown – density increases now greatly lag price increases. If the design company cannot pass on cost increases to customers, and is stuck at that $140 price, gross margins fall to 22%, which is not good.

We can play around with the numbers and debate the extent to which chip designers can pass on these costs to their customers, but the conclusion remains the same: as TSMC raises prices, producing chips at the leading edge becomes increasingly unfeasible for a growing segment of customers.

The example above is loosely based on Qualcomm, so they would fall into this category, but the same applies to AMD. The hardest hit will be customers with smaller volumes, spanning from start-ups to hyperscalers. For many, Moore's Law becomes extremely challenging. Of course, Nvidia and a few other companies have significantly more flexibility to absorb these costs, but many – if not most – companies do not.

We expect that TSMC is unlikely to push its customers this hard, but the reality is that they could.

Some might argue that TSMC has effectively held a monopoly for several years and could have raised prices in this way long ago. The fact that they haven't suggests they won't in the future. However, conditions are changing.

Until recently, a cautious and paranoid TSMC needed to worry about Intel or Samsung becoming competitive again. That now seems increasingly unlikely. And this is why Intel Foundry matters. Today, some may credibly argue that there is no commercial necessity for Intel Foundry in the industry – that customers do not need a second source beyond TSMC.

But look ahead a few years, to a world where TSMC can freely raise prices. In that scenario, everyone will be desperately searching for an alternative.

Masthead credit: Fritzchen Fritz

English (US) ·

English (US) ·