It’s been more than 160 years since Archaeopteryx first shook up science as the missing link—part reptile, part bird—and indicated that today’s pigeons and parakeets are the feathery descendants of dinosaurs.

But despite decades of research, there’s still more to learn. Case in point: a newly described fossil, nicknamed the Chicago Archaeopteryx, may be the most detailed and revealing specimen yet.

“The most important findings all center around rarely preserved soft tissues. For the first time we see the soft tissue of the hand and foot,” said Jingmai O’Connor, lead author of the new study in Nature and associate curator of fossil reptiles at the Field Museum, in an email to Gizmodo.

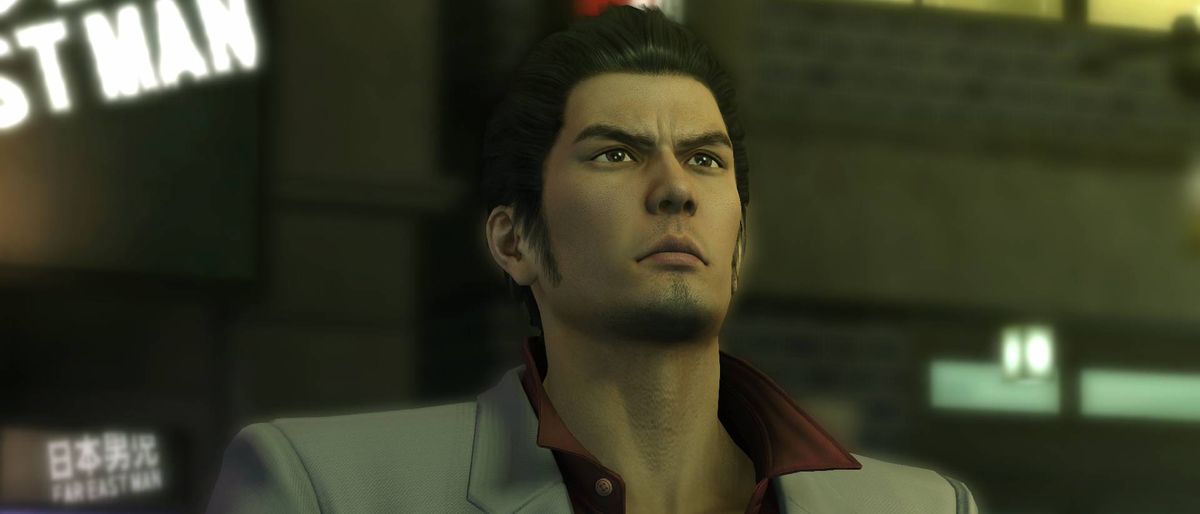

Artist’s depiction of Archaeopteryx. © Michael Rothman

Artist’s depiction of Archaeopteryx. © Michael RothmanWith that information, paleontologists are getting a more nuanced understanding of the creature than they’ve ever had.

“The tissue on the right hand suggests that the two main digits of the hand were not bound together in soft tissue and that the third digit could move independently, supporting long abandoned claims from the 90s that Archaeopteryx could use its hands to climb,” O’Connor added.

The fossil had been in private hands since 1990, but made its public debut at Chicago’s Field Museum last year. At roughly the size of a pigeon, the Chicago Archaeopteryx is the smallest specimen yet found, and was pulled from the same German limestone where all Archaeopteryx fossils come from.

What sets this fossil apart is its pristine preservation and exhaustive preparation. Over a year of painstaking work by the Field’s fossil prep team, led by the museum’s chief preparator Akiko Shinya, revealed bones and soft tissues that had never been visible before. That tissue included a set of upper wing feathers called tertials, which may have helped Archaeopteryx fly when many of its dinosaur cousins couldn’t.

The team used UV light and CT scans to carefully chip away the rock encasing the bird’s mineralized remains, sometimes removing just fractions of a millimeter to avoid damaging tissue. The result is the most complete and delicately preserved Archaeopteryx yet.

Among the findings: scales on the bottom of the animal’s toes, soft tissue in the fingers, and fine details in the skull that could help explain how modern birds evolved flexible beaks. But the key takeaway in this paper is evidence of the creature’s flight. While earlier dinosaurs had feathers and wings, Archaeopteryx may have been the first to actually take wing, based on the tertials, which are missing in feathered dinosaurs that aren’t quite birds.

Though non-avian dinosaurs couldn’t fly, this spunky critter could. That supports the idea that flight evolved more than once in dinosaurs—an exceptionally cool notion that serves as a reminder that Archaeopteryx is merely one branch of the tree of life—albeit a very neat one.

And as for this fossil, O’Connor says we’re only just scratching the surface. More analysis of the Chicago Archaeopteryx will reveal more details of how these flying dinosaurs lived.

“Some very cool and surprisingly bird-like new features of the skull; chemical data about the soft tissues; the full body CT scan, and much, much more are still to come,” O’Connor added.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·