The rise of AI, hyperscale clouds, and the general need for performance have significantly transformed the design and cooling of data centers in 2025. However, the rapid evolution of AI and adjacent technologies will change the scale of data centers and drive the adoption of even more sophisticated cooling technologies over the next decade, so let's examine what the future holds.

Just 10 years ago, in 2015, data center liquid cooling was primarily limited to specialized applications such as supercomputers and mining farms; its global adoption rate at the time was at best around 5%. Air cooling dominated due to lower upfront costs and simpler infrastructure. But by 2020, the adoption of liquid cooling began to rise and reached around 10% as cloud hyperscalers started to strive for efficiency . However, with power densities of approximately 5 –10kW per rack on average, air cooling was sufficient for most.

Air cooling

Traditionally, data centers have used air cooling to keep operations running, and for many operators, that's not going to change any time soon. However, as thermal densities increase, the technology's limitations become more apparent. So, let's examine how it all works in practice.

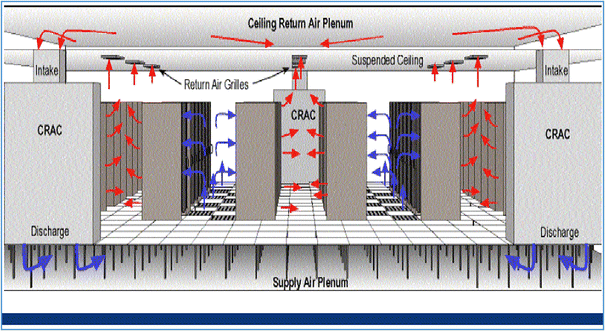

Air cooling in data centers works by circulating conditioned air to absorb and remove the heat produced by servers and networking equipment. Typically, air cooling keeps intake air around 21°C to 24°C — the range recommended for safe operation — by continuously pushing cool air toward the servers and drawing warm exhaust air back for reconditioning.

Most air-cooled facilities are organized using a hot aisle/cold aisle layout to prevent mixing of hot air and cold air, and to ultimately lower energy bills. Racks are arranged so that the fronts (intakes for cool air) of servers face each other across a cold aisle, while the backs (exhausts for heated air) face each other across a hot aisle. Some data centers go further by enclosing either the hot or cold aisles with physical barriers to completely separate air streams and minimize energy waste.

The hot air rises to return to an air plenum through return grilles, from where it is taken in by actual cooling systems, such as a Computer Room Air Conditioner (CRAC), or Computer Room Air Handler (CRAH) unit. CRAC units use refrigerants to cool air directly, similar to standard air conditioners, while CRAH units circulate air through coils cooled by chilled water supplied from an external chiller device. The cooled air is then distributed through a raised floor supply plenum or overhead ducts and directed into the cold aisles. After absorbing heat from the hot aisle, the air returns through ceiling plenums to the cooling units, where it is further cooled.

Many modern air-cooled facilities also use economizers or free cooling systems to reduce energy consumption. These systems leverage cool outdoor air or low ambient temperatures to assist with, or even replace, CRAC or CRAH cooling. In regions with mild climates, this can significantly cut electricity use by minimizing compressor operation.

Although air cooling remains a standard data center cooling technology, it becomes less effective for high-density server racks with power draws of 20 kW – 30 kW, as it cannot efficiently remove enough heat. As a result, data centers are increasingly adopting liquid- or hybrid-cooling systems.

Hybrid and liquid cooling

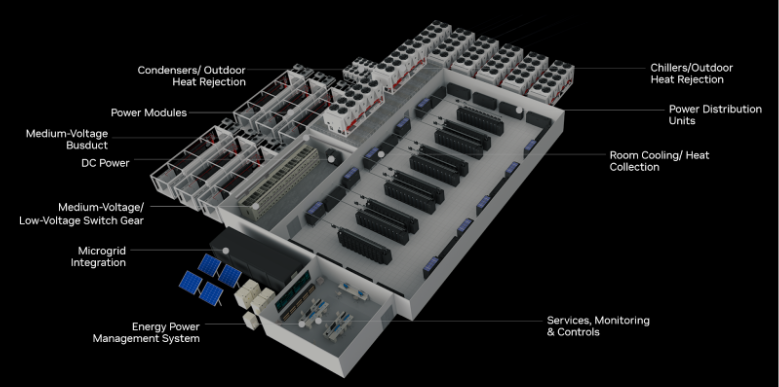

Hybrid and liquid cooling systems in data centers are designed to handle the higher heat loads of AI and HPC servers, each of which can easily consume several kilowatts of power. Instead of relying solely on chilled air, these systems use liquid coolant (typically water or a dielectric fluid) to directly absorb and remove heat from components or, in rare cases, from localized air zones.

In a hybrid cooling setup, both air and liquid are used together. Cold air still circulates through the room to maintain ambient conditions, but liquid loops handle the hottest components, such as CPUs and GPUs (and maybe even SSDs in the not-so-distant future). In this case, the heat is captured by a circulating coolant that carries it to a cooling distribution unit (CDU). From there, the thermal energy is either transferred to facility water loops and cooling towers or partially released via evaporative cooling before being vented to the outside.

Depending on the exact setup, CRAC or CRAH can account for 15%-20% of the cooling capacity, while the majority of the thermal load is handled by the liquid-cooling system. In many cases, hybrid cooling can be implemented in existing premises without requiring a complete facility redesign.

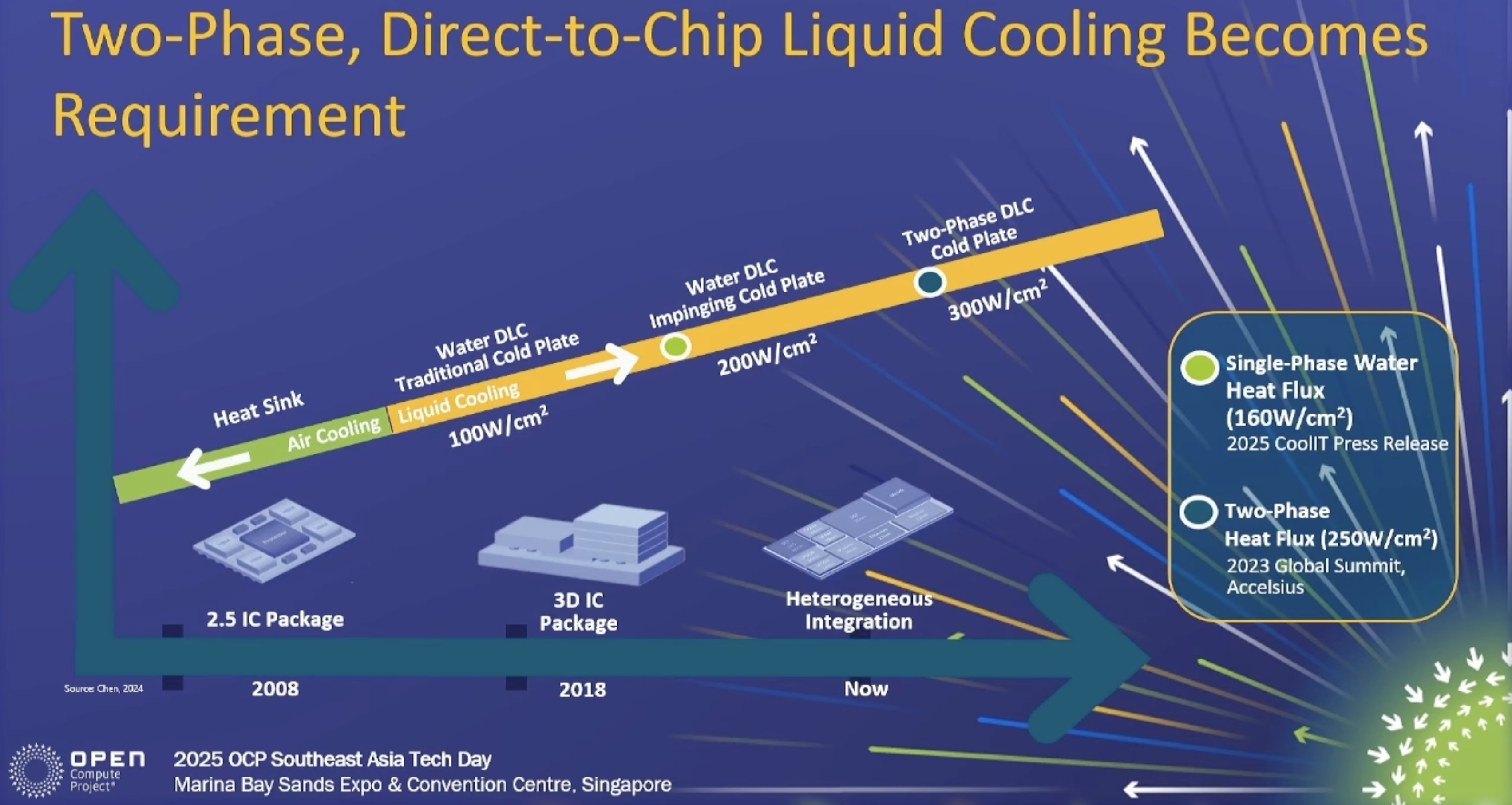

Companies like AMD and Nvidia recommend using direct-to-chip (D2C) liquid cooling for their current AI accelerators, which dissipate hundreds of watts per square centimeter. AI processors will continue to scale their power to 4.4kW with Nvidia's Feynman GPUs in 2028. Such a gargantuan thermal energy draw puts very strict requirements both on the whole cooling system and each of its components. One of the most demanding components in this case will be the D2C coldplate, which must absorb and remove kilowatts of heat from the AI accelerators.

Today, Nvidia's Blackwell Ultra — containing two compute chiplets (each at a near-reticle-limit die size, or up to 858 mm^2) and eight HBM3E memory stacks (each at 121 mm^2) — dissipates up to 1,400W of power. If the total silicon area of Blackwell Ultra is around 2,850 mm^2, then its heat dissipation is approximately 49.1W/cm^2. Such power density can be met with existing single-phase liquid-cooling solutions at a heat flux of 100W/cm^2; however, performance may degrade under high loads, as GPU hot spots can have much higher thermal density than the rest of the chip, necessitating throttling.

As the power draw of next-generation GPUs rises to 4.4kW and above, their power density will increase, necessitating more advanced coldplates and cooling systems. For example, CoolIT this year demonstrated a single-phase Split-Flow D2C coldplate with a heat flux shy of 200W/cm^2, which could cool up to 4000W. Accelsius says that for even more power-hungry GPUs, it can enable a heat flux of 300W/cm^2 using two-phase D2C cooling.

For those unfamiliar, a two-phase direct-to-chip cooling system uses a low-boiling-point dielectric fluid that flows through sealed cold plates attached directly to CPUs or GPUs. The fluid boils on contact with the heat source, absorbing energy, then condenses back into liquid in a nearby heat exchanger. This phase change between liquid and vapor transfers far more heat than a single-phase liquid system, enabling it to handle very high power densities (up to ~1,000 W/cm^2). The process is typically passive, requiring little pumping power, and the recovered heat can be rejected through the cooling capabilities of the facility.

Frore says its LiquidJet coldplate — which is said to be Feynman-ready — can sustain a hotspot density of 600 W/cm^2 at 40°C inlet temperature, though the company hasn't disclosed whether it used a single-phase or dual-phase D2C cooling system for testing.

Hybrid and liquid cooling with D2C coldplate cooling technologies are increasingly used in AI and hyperscale data centers, as they reduce energy use (compared to air cooling) and enable higher rack densities. As compute power continues to rise, these cooling methods are becoming vital, with 2P D2C cold plates undoubtedly becoming a crucial part of it all in the coming years. However, for some systems, these cooling methods may not be sufficient in the future, prompting the industry to look to even more complex cooling methods.

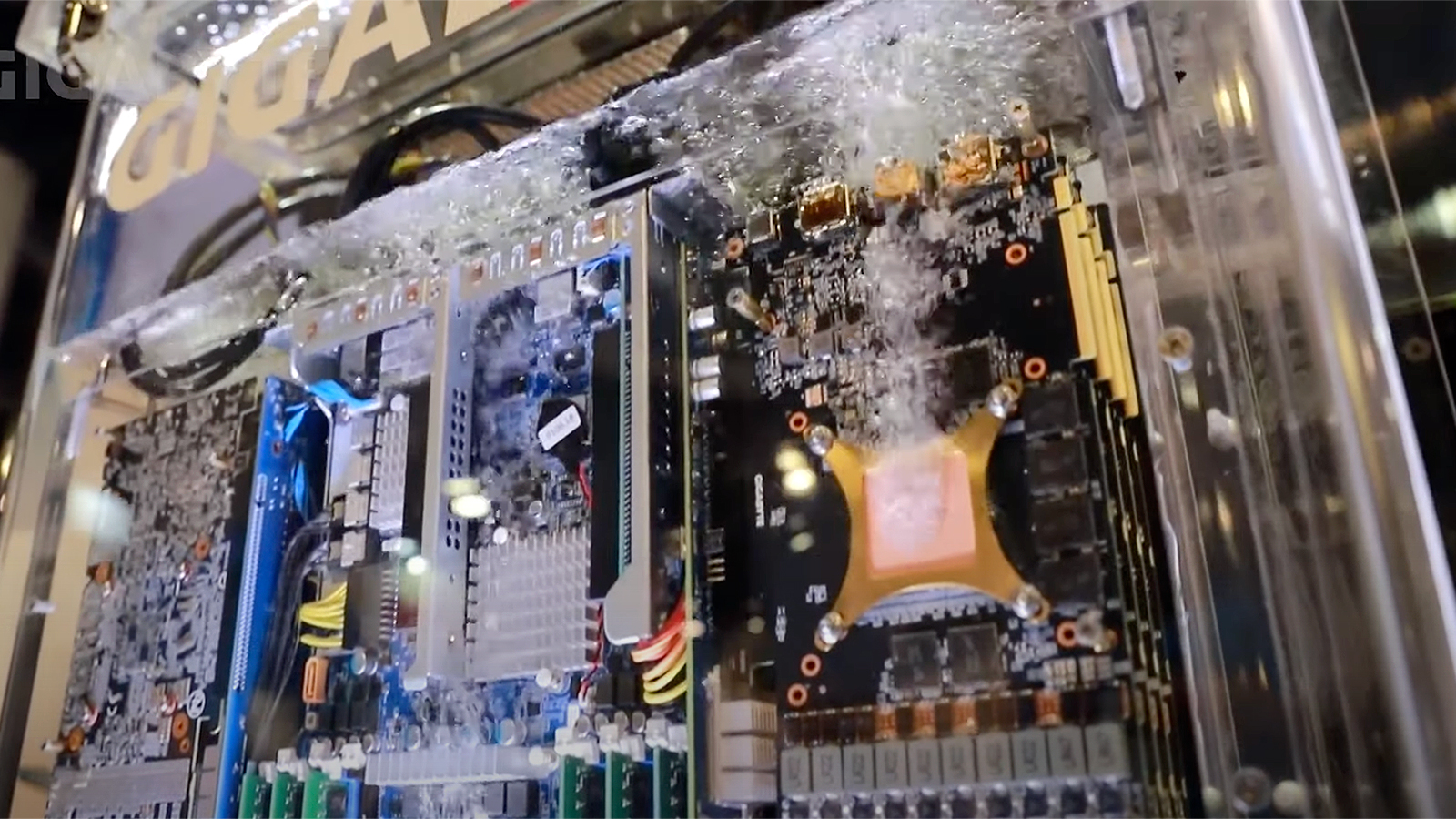

Immersion cooling

One such method is immersion cooling, where entire servers or boards are submerged in a dielectric fluid that does not conduct electricity, but which can remove more heat and at a faster pace than contemporary coldplates. Since we recently published a rather in-depth story on immersion cooling, we will not dive into the technology here.

Immersion cooling — especially two-phase immersion systems that use oils with a low boiling point that boil into vapor and condense back to liquid at the top of the tank — can handle extremely high heat fluxes. Typical sustained heat flux in a single-phase immersion cooling system is in the range of 250W/cm^2 at the chip surface, but with optimized coldplates or enhanced surfaces, some studies report up to 300 W/cm^2.

Meanwhile, with two-phase immersion cooling, we are talking about ~1500W/cm^2 and potentially higher. While advanced immersion cooling has its own caveats, including costs and the need to build new facilities, the industry is developing embedded cooling solutions that cool chips from the inside.

Embedded cooling

The term 'embedded cooling' typically refers to a very broad set of cooling technologies that are integrated very close to a chip, or sometimes even a die itself. For example, it can mean microfluidic channels built into (or directly on) a chip substrate, which transfers heat away from hot spots on a chip or IC. The term encompasses a broad range of technologies, but we will focus on realistic approaches that have been described in academic publications or experimentally demonstrated (e.g., by Microsoft), even though there are more exotic methods for cooling chips using lasers.

Normally, with embedded cooling, we think of microchannels or pin-fin arrays built directly into the chip substrate or package so that coolant can flow very close to the transistors that generate heat. Such an approach greatly shortens the thermal path between the silicon and the coolant, as these microstructures remove heat far more efficiently than traditional cold plates because the liquid absorbs thermal energy directly at the hotspots. A bonus is that this approach is poised to achieve uniform temperatures across the die and prevent thermal throttling in dense 2D/3D SiPs.

In terms of performance, embedded features can handle heat fluxes approaching 1000 W/cm^2 in laboratory settings. While this may not sound impressive given the capabilities of today's immersion cooling in lab environments, it is a major achievement. What is more important is that such microchannels are meant to take away heat from hotspots — enabling more predictable performance from individual processors and from the whole data center — which external heat spreaders of cold plates cannot do.

Today, several companies are developing embedded cooling solutions, including Adeia, HP, Nvidia, Microsoft, and TSMC. In fact, some of their solutions are already commercially available.

Adeia

Adeia, a spin-off from Xperi, is not a chipmaker but a 'pure play R&D company' that owns numerous advanced chip packaging and hybrid bonding-related patents. Recently, the company announced its silicon-integrated liquid cooling system (ICS), which is essentially a silicon cold plate that bonds directly onto the processor, so the coolant runs inside silicon bonded to the chip rather than through an external copper cold plate. Tests at power densities of 1.5–2 W/mm^2 (150–200 W/cm^2) show up to 70% lower total thermal resistance and up to 80% better performance than standard metal cold plates.

The ICS design replaces a typical microchannel structure with silicon-based flow geometries, such as staggered or rectangular posts and triangular channels, improving both heat removal and fluid efficiency. Adeia reported that staggered posts cut peak temperatures by about 4°C, while rectangular posts reduced pressure loss by 4X. A full-length microchannel variant reached a ninefold pressure-drop improvement over post arrays, according to the company. While Adeia's ICS qualifies as a form of embedded cooling as it integrates the cooling layer directly into the silicon package stack, a secondary system, such as air or liquid cooling, is still necessary to remove the heat that the ICS transfers away from the chip itself.

HP and Nvidia

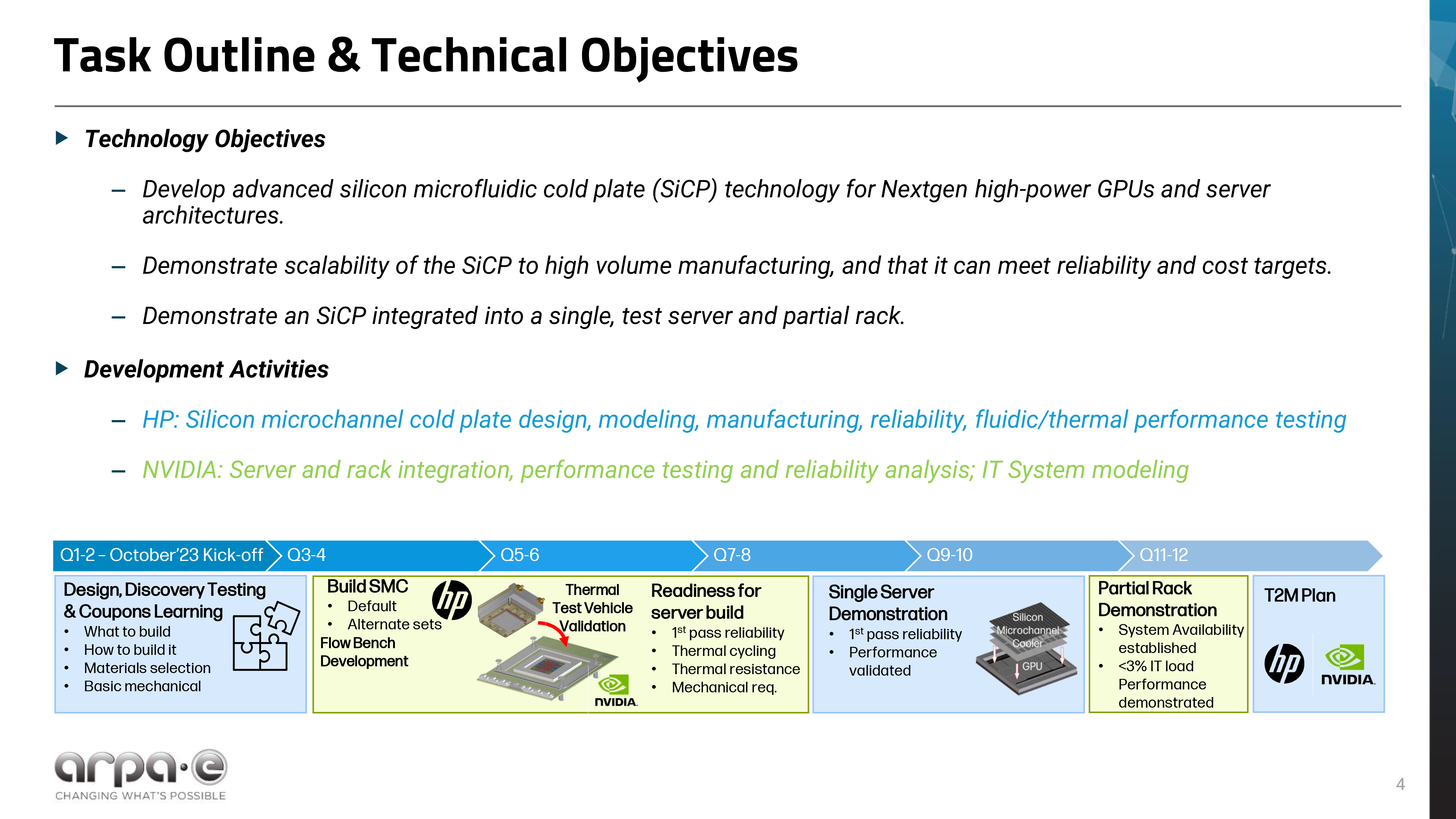

HP and Nvidia have also been working on a silicon-based microfluidic cooling system for next-generation high-performance GPUs since 2023. The goal is to create a compact, single-phase liquid cooler that attaches directly to the GPU surface and can later be embedded deeper into the package. The ongoing project has received $3.25 million in federal support from the ARPA-E Coolerchips initiative

The new Silicon Microchannel Cold Plate (SiCP) uses HP's fifth-gen MEMS microfluidic technology to manage coolant flow through fine silicon channels and through-silicon vias. SiCP targets a thermal resistance of about 0.01 K/W, a pressure drop below 60 kPa, and the ability to remove up to 2kW of heat at a flow rate of under 3 L/min, according to a presentation from the two companies. HP and Nvidia aim to bond an SiCP with a GPU using a very thin metallic bond with minimal thermal resistance. The technology aims to dissipate over 1kW of power and reject waste heat to 40°C ambient air, using only ~1.27% of server power for pumping.

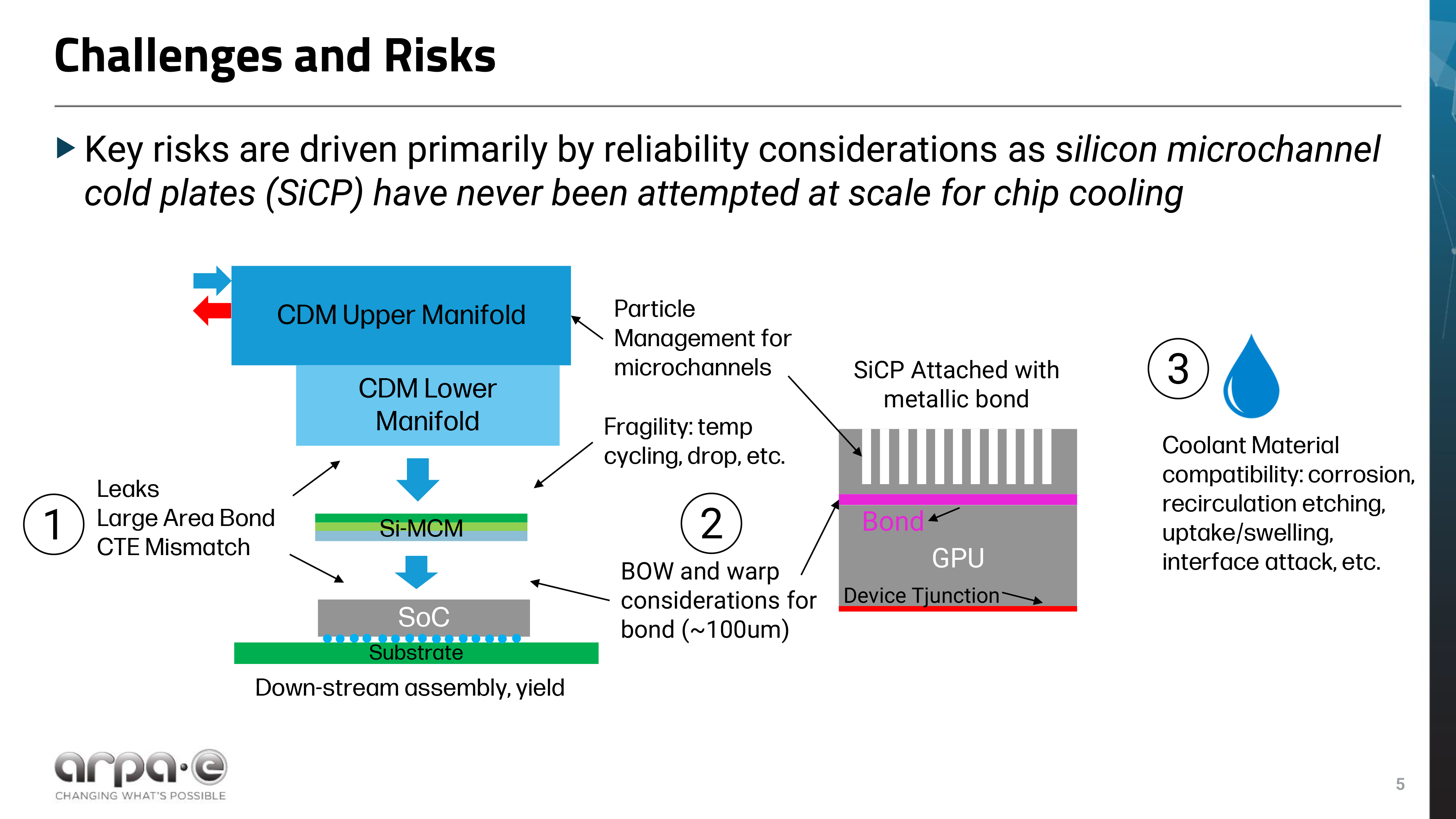

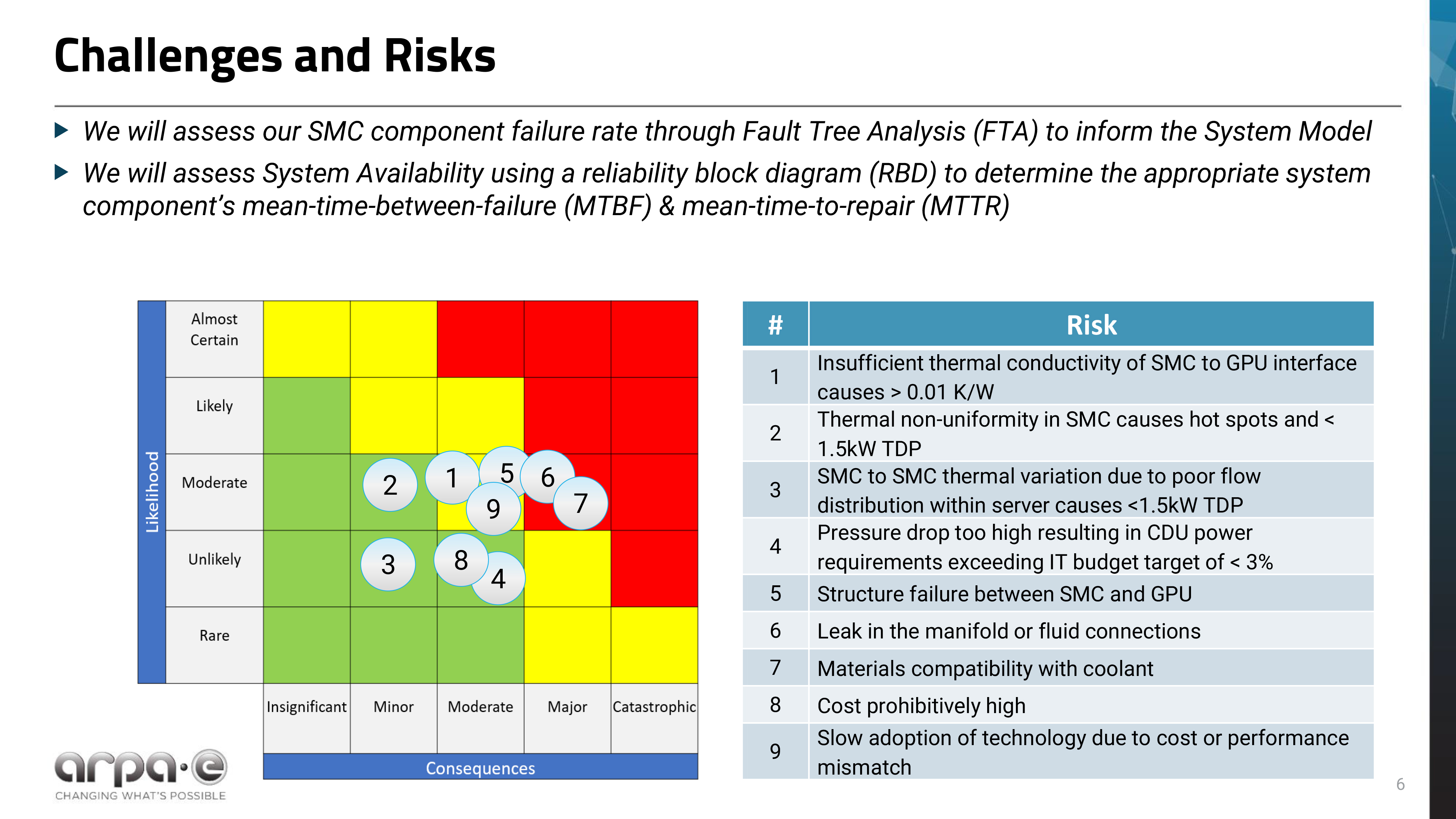

HP and Nvidia acknowledge that their SiCP faces several technical challenges, including mechanical stress, thermal expansion mismatch, coolant compatibility, and channel clogging, that they must address. Meanwhile, reliability is the primary risk, as SiCP has never been used in cooling devices.

HP and Nvidia are designing their SiCP devices as drop-in upgrades for existing liquid-cooled servers slated for deployment in 2026–2028, though the companies have yet to demonstrate actual cooling solutions.

Microsoft collaborated with Swiss startup Corintis to build its microchannel design. Instead of straight grooves, the resulting layout follows organic patterns resembling leaf veins or butterfly wings to distribute coolant more efficiently. The channels must remain extremely fine to remove heat effectively, yet shallow enough to avoid weakening the silicon and causing structural damage. There is a challenge with the Microsoft-Corintis design, as these microchannels require extra processing steps to be etched, which increases costs.

To simplify production, Microsoft patented an approach that builds the microfluidic cooling plate separately, then attaches it to one or two chips, an approach that largely resembles that of Frore, albeit on a different scale. The company has already identified the best coolant, refined etching precision, and successfully integrated the process into its manufacturing flow. Hence, the technology is now ready for large-scale deployment and licensing, though Microsoft has not yet signed any contracts.

TSMC

Arguably, the most promising embedded cooling platform is TSMC's Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling (also known as Si‑Integrated Micro‑Cooler, or IMC-Si), which is designed to embed microfluidic channels directly into the silicon structure. The technology is part of TSMC's 3DFabric advanced packaging platform, making it the closest to actual product implementation, as the company has already demonstrated.

TSMC has experimented with on-chip liquid cooling since around 2020 and has even demonstrated that it can cool a 2.6kW system-in-package using this technology several years ago. TSMC's Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling system uses elliptical micropillars and a compartmentalized fluid layout, etched directly into the silicon using the company's SoIC wafer-to-wafer bonding technology. This structure routes coolant a few micrometers away from active transistors, thereby spreading heat from hot spots uniformly across the die with minimal pressure loss.

Tests conducted by TSMC with deionized water as coolant demonstrated that Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling could cool a reticle-sized die dissipating 2kW of power (about 3.2 W/mm^2) using 40°C water with less than 10W of pump power. The technology can even maintain local hot spots of 14.6W/mm^2 (even above 20W/mm^2 under reduced total load) without exceeding thermal limits.

In data centers, it can reduce overall cooling infrastructure requirements by nearly half, according to TSMC. The technology is also compatible with immersion-style thermal management setups, which opens doors to next-generation AI and HPC processors that could consume as much as 15,360W of power, as envisioned by KAIST. Direct-to-Silicon Liquid cooling can also enable better cooling, higher efficiency, and expanded performance for rack applications.

When integrated into the CoWoS-R packaging platform, the system handled over 2.6kW continuous heat load and achieved roughly 15% lower thermal resistance than conventional liquid-cooled assemblies that rely on thermal paste, according to TSMC. Furthermore, the bonded structure endured 160µm – 190µm of warpage without leaks, TSMC claims. In fact, the experimental device has passed the NASA-STD-7012A helium-based reliability test with leakage rates below 115 cc/year, which is well within data-center standards. However, it is unclear whether an embedded cooling system can maintain its efficiency in the presence of leaks.

TSMC plans to deploy Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling commercially around 2027 (potentially in time for Nvidia's Feynman architecture in 2028), when it will become part of multi-chiplet, multi-reticle-sized AI accelerators packaged using TSMC's CoWoS technology. However, it remains to be seen how the technology might evolve from there.

The state of play

Over the past decade, data center cooling has shifted from simple air-based systems toward liquid and hybrid cooling systems, primarily driven by soaring power consumption of AI servers and larger cloud infrastructure deployed by hyperscalers. Air cooling, once dominant, still serves legacy facilities, but as rack power rises beyond 40kW to 140kW and higher, liquid-based systems — which held 46% of the market in 2024 — are becoming the standard for new AI and some cloud builds.

But the shift towards hybrid cooling with direct-to-chip (D2C) cold plates is only the beginning of a larger shift to more advanced technologies, as companies are now considering immersion and embedded cooling methods.

Next-generation direct-to-chip cold plates from Accelsius and CoolIT are expected to deliver heat flux of up to 300 W/cm^2. In contrast, Frore is demonstrating that cold plates can sustain a hotspot density of 600 W/cm^2. Immersion systems reach ~1500 W/cm^2 in two-phase form. Meanwhile, embedded cooling addresses the hot-spot problem by bringing microchannels or pin-fin arrays directly into silicon to dissipate heat at the transistor level.

Multiple companies — from patent holder Adeia to HP, Nvidia, Microsoft, and TSMC — are developing various forms of embedded cooling technology. Yet TSMC's Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling appears to be the closest and most suitable for commercialization, as the company currently produces the lion's share of AI accelerators.

10 hours ago

15

10 hours ago

15

English (US) ·

English (US) ·