Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

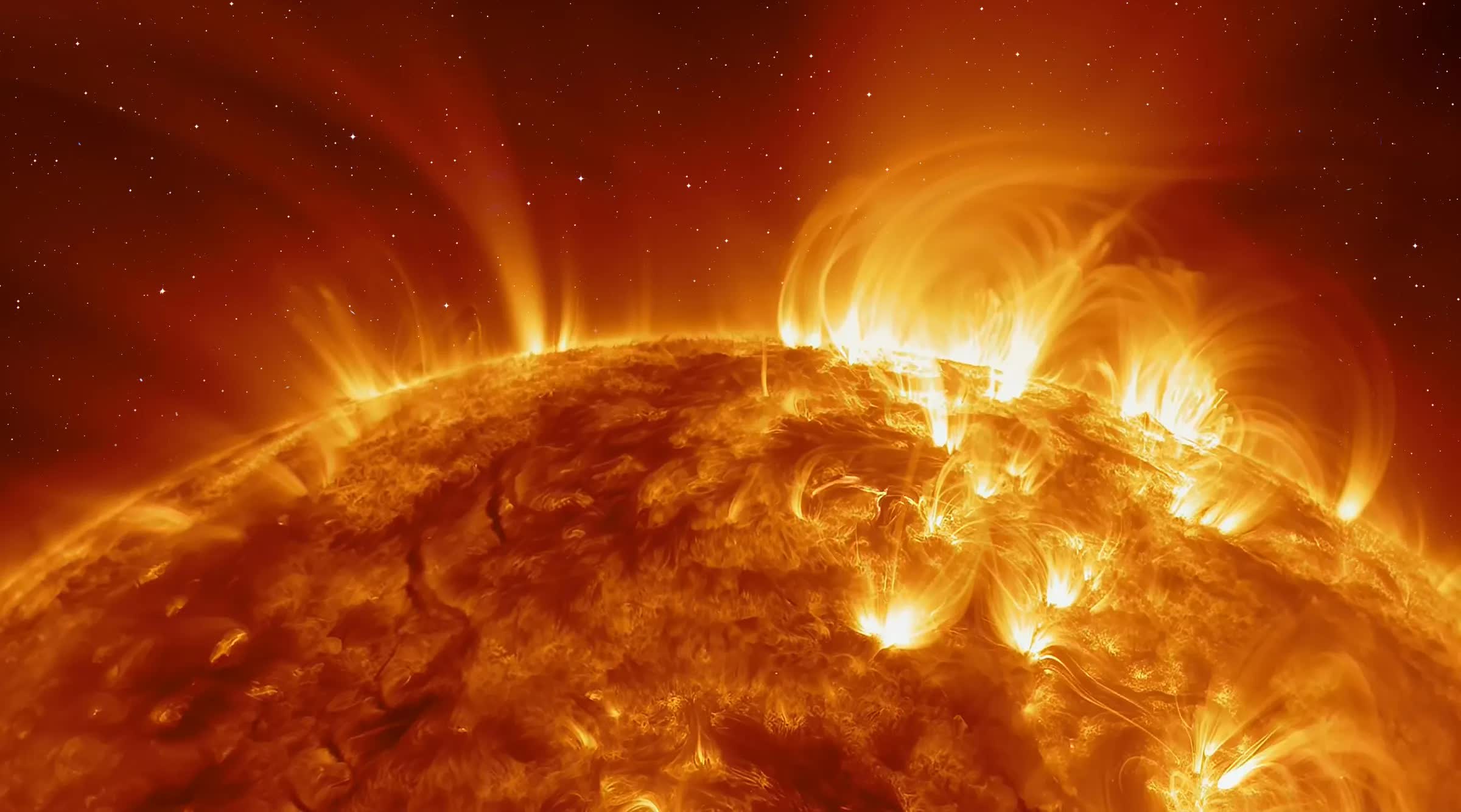

In a nutshell: If you thought getting hit by a massive solar flare from our sun was a freak occurrence, there's some bad news. New research suggests that killer superflares may actually be a lot more common than we previously thought.

Superflares are intense solar storms up to 10,000 times stronger than regular flares that release intense electromagnetic radiation and energetic particles into space. This radiation can fry electronics, wipe data servers, and send satellites crashing back to Earth. While their effects may not have been so far-reaching a century or so ago, they could prove devastating in a modern world that basically runs on these technologies.

The study, conducted by astronomers at the Max Planck Institute and published in the journal Science, looked at over 56,000 sun-like stars observed by NASA's Kepler telescope between 2009-2013. During that window, they identified a staggering 2,889 superflares erupting from 2,527 of those stars.

Previously, estimates based on more limited samples suggested our type of star might only belch out one of these flares every few thousand years. But this new, more comprehensive analysis indicates sun-like stars likely experience them about once per century on average.

Why the sudden, dramatic jump in projected superflare frequency for our sun? The researchers attribute it to overcoming biases in earlier studies that excluded many sun-like stars by only considering those with similar rotation periods to our star.

"We employed a new flare detection method developed by our group to identify flare sources in light curves and images with sub-pixel resolution, accounting for instrumental effects," Valeriy Vasilyev, the Max Planck doctoral student who led the work, explained to Live Science.

The potential implications for Earth are concerning. The infamous 1859 Carrington Event, one of the most powerful solar storms in recent history, already released energy equivalent to 10 billion single-megaton nuclear bombs when it struck our planet.

Of course, the new study doesn't prove our sun will certainly unleash such an extreme event soon. There are still open questions, like potential differences between the observed flaring stars and our own sun's conditions. One is that 30% of those flaring stars exist in binary pairs which can trigger superflares through tidal forces – something not applicable to our solitary star.

The researchers acknowledge further investigation is needed to nail down the true risk our sun poses to Earth's infrastructure and systems. Better space weather forecasting and monitoring, aided by future sun-observing missions like the European Space Agency's Vigil probe due to launch in 2031, could help provide more clarity.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·