The launch of another important mission, NASA's Europa Clipper, is on hold due to Hurricane Milton.

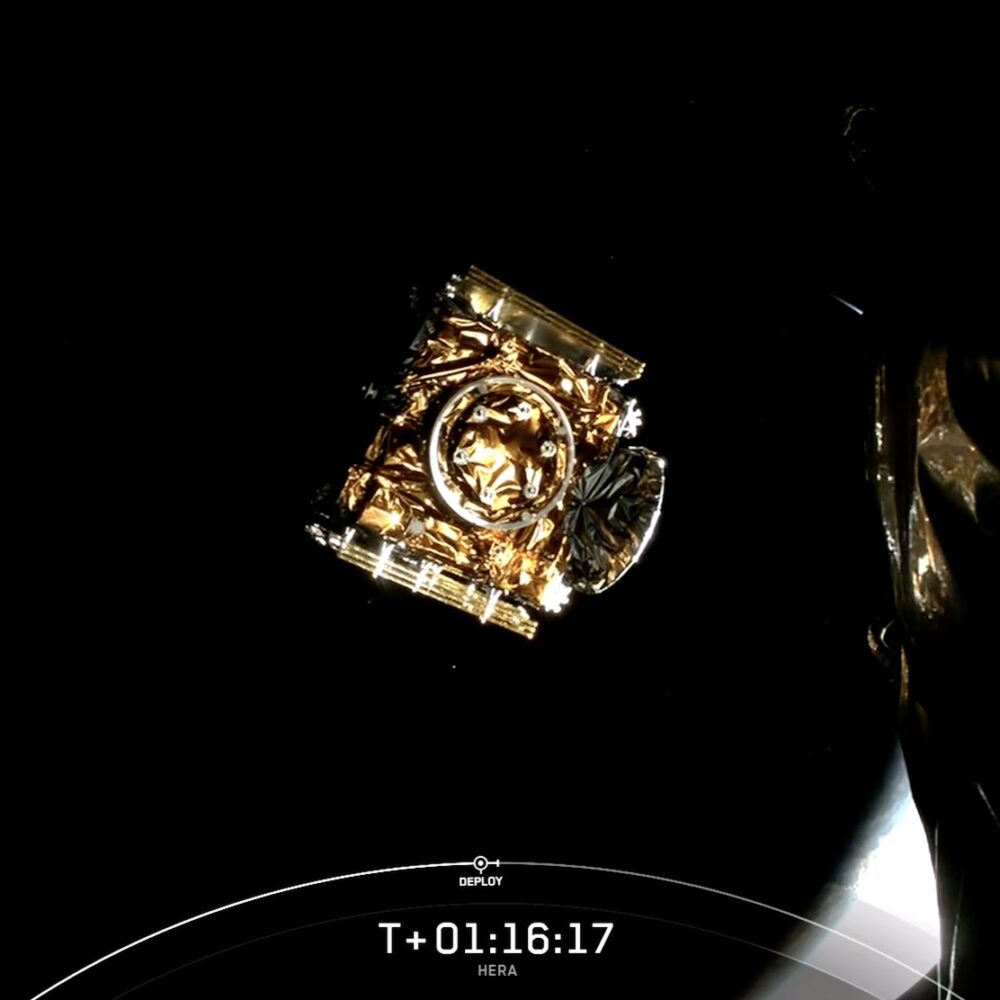

The European Space Agency's Hera spacecraft flies away from the Falcon 9 rocket's upper stage a little more than an hour after liftoff Monday. Credit: SpaceX

Two years ago, a NASA spacecraft smashed into a small asteroid millions of miles from Earth to test a technique that could one day prove useful to deflect an object off a collision course with Earth. The European Space Agency launched a follow-up mission Monday to go back to the crash site and see the damage done.

The nearly $400 million (363 million euro) Hera mission, named for the Greek goddess of marriage, will investigate the aftermath of a cosmic collision between NASA's DART spacecraft and the skyscraper-size asteroid Dimorphos on September 26, 2022. NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission was the first planetary defense experiment, and it worked, successfully nudging Dimorphos off its regular orbit around a larger companion asteroid named Didymos.

But NASA had to sacrifice the DART spacecraft in the deflection experiment. Its destruction meant there were no detailed images of the condition of the target asteroid after the impact. A small Italian CubeSat deployed by DART as it approached Dimorphos captured fuzzy long-range views of the collision, but Hera will perform a comprehensive survey when it arrives in late 2026.

"We are going to have a surprise to see what Dimorphos looks like, which is, first, scientifically exciting, but also important because if we want to validate the technique and validate the model that can reproduce the impact, we need to know the final outcome," said Patrick Michel, principal investigator on the Hera mission from Côte d’Azur Observatory in Nice, France. "And we don’t have it. With Hera, it’s like a detective going back to the crime scene and telling us what really happened."

Last ride before the storm

The Hera spacecraft, weighing in at 2,442 pounds (1,108 kilograms), lifted off on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket at 10:52 am EDT (14:52 UTC) Monday from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida.

Officials weren't sure the weather conditions at Cape Canaveral would permit a launch Monday, with widespread rain showers and a blanket of cloud cover hanging over Florida's Space Coast. But the conditions were just good enough to be acceptable for a rocket launch, and the Falcon 9 lit its nine kerosene-fueled engines to climb away from pad 40 after a smooth countdown.

SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, with ESA's Hera mission. Credit: SpaceX

This was probably the final opportunity to launch Hera before the spaceport shutters in advance of Hurricane Milton, a dangerous Category 5 storm taking aim at the west coast of Florida. If the mission didn't launch Monday, SpaceX was prepared to move the Falcon 9 rocket and the Hera spacecraft back inside a hangar for safekeeping until the storm passes.

Meanwhile, at NASA's Kennedy Space Center a few miles away, SpaceX is securing a Falcon Heavy rocket with the Europa Clipper spacecraft to ride out Hurricane Milton inside a hangar at Launch Complex 39A. Europa Clipper is a $5.2 billion flagship mission to explore Jupiter's most enigmatic icy moon, and it was supposed to launch Thursday, the same day Hurricane Milton will potentially move over Central Florida.

NASA announced Sunday that it is postponing Europa Clipper's launch until after the storm.

"The safety of launch team personnel is our highest priority, and all precautions will be taken to protect the Europa Clipper spacecraft," said Tim Dunn, senior launch director at NASA’s Launch Services Program. "Once we have the 'all-clear' followed by facility assessment and any recovery actions, we will determine the next launch opportunity for this NASA flagship mission."

Europa Clipper must launch by November 6 in order to reach Jupiter and its moon Europa in 2030. ESA's Hera mission had a similarly tight window to get off the ground in October and arrive at asteroids Didymos and Dimorphos in December 2026.

Returning to flight

The Falcon 9 did its job Monday, accelerating the Hera spacecraft to a blistering speed of 26,745 mph (43,042 km/hr) with successive burns by its first stage booster and upper stage engine. This was the highest-speed payload injection ever achieved by SpaceX.

SpaceX did not attempt to recover the Falcon 9's reusable booster on Monday's flight because Hera needed all of the rocket's oomph to gain enough speed to escape the pull of Earth's gravity.

"Good launch, good orbit, and good payload deploy," wrote Kiko Dontchev, SpaceX's vice president of launch, on X.

This was the first Falcon 9 launch in nine days—an unusually long gap between SpaceX missions—after the rocket's upper stage misfired during a maneuver to steer itself out of orbit following an otherwise successful launch September 28 with a two-man crew heading for the International Space Station.

The upper stage engine apparently "over-burned," and the rocket debris fell into the atmosphere short of its expected reentry corridor in the Pacific Ocean, sources said. The Federal Aviation Administration grounded the Falcon 9 rocket while SpaceX investigates the malfunction, but the FAA granted approval for SpaceX to launch the Hera mission because its trajectory would carry the rocket away from Earth, rather than back into the atmosphere for reentry.

"The FAA has determined that the absence of a second stage reentry for this mission adequately mitigates the primary risk to the public in the event of a reoccurrence of the mishap experienced with the Crew-9 mission," the FAA said in a statement.

Members of the Hera team from ESA and its German prime contractor, OHB, pose with the spacecraft inside SpaceX's payload processing facility in Florida. Credit: SpaceX

This was the third time the FAA has grounded SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket fleet in less than three months, following another upper stage failure in July that caused the destruction of 20 Starlink Internet satellites and the crash-landing of a Falcon 9 booster on an offshore drone ship in August. Federal regulators are responsible for ensuring commercial rocket launches don't endanger the public.

These were the first major anomalies on any Falcon 9 launch since 2021.

It's not clear when the FAA will clear SpaceX to resume launching other Falcon 9 missions. However, the launch of the Europa Clipper mission on a Falcon Heavy rocket, which uses essentially the same upper stage as a Falcon 9, is not licensed by the FAA because it is managed by NASA, another government agency. NASA will have final authority on whether to give the green light for the launch of Europa Clipper.

Surveying the damage

ESA's Hera spacecraft is on course for a flyby of Mars next March to take advantage of the red planet's gravity to slingshot itself on a trajectory to intercept its twin target asteroids. Near Mars, Hera will zoom relatively close to the planet's asteroid-like moon, Deimos, to obtain rare closeups.

Then, Hera will approach Didymos and Dimorphos a little more than two years from now, maneuvering around the binary asteroid system at a range of distances, eventually moving as close as about a half-mile (1 kilometer) away.

Italy's LICIACube spacecraft snapped this image of asteroids Didymos (lower left) and Dimorphos (upper right) a few minutes after the impact of DART on September 26, 2022. Credit: ASI/NASA

Dimorphos orbits Didymos once every 11 hours and 23 minutes, roughly 32 minutes shorter than the orbital period before DART's impact in 2022. This change in orbit proved the effectiveness of a kinetic impactor in deflecting an asteroid that threatens Earth.

Dimorphos, the smaller of the two asteroids, has a diameter of around 500 feet (150 meters), while Didymos measures approximately a half-mile (780 meters) wide. Neither asteroid poses a risk to Earth, so NASA chose them as the objective for DART.

The Hubble Space Telescope spotted a debris field trailing the binary asteroid system after DART's impact. Astronomers identified at least 37 boulders drifting away from the asteroids, material ejected when the DART spacecraft slammed into Dimorphos at a velocity of 14,000 mph (22,500 kmh).

Scientists will use Hera, with its suite of cameras and instruments, to study how the strike by DART changed the asteroid Dimorphos. Did the impact leave a crater, or did it reshape the entire asteroid? There are "tentative hints" that the asteroid's shape changed after the collision, according to Michael Kueppers, Hera's project scientist at ESA.

"If this is the case, it would also mean that the cohesion of Dimorphos is extremely low; that indeed, even an object the size of Dimorphos would be held together by its weight, by its gravity, and not by cohesion," Kueppers said. "So it really would be a rubble pile.”

Hera will also measure the mass of Dimorphos, something DART was unable to do. "That is important to measure the efficiency of the impact... which was the momentum that was transferred from the impacting satellite to the asteroid," Kueppers said.

This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image of the asteroid Dimorphos was taken on December 19, 2022, nearly three months after the asteroid was impacted by NASA’s DART mission. Hubble’s sensitivity reveals a few dozen boulders knocked off the asteroid by the force of the collision.

Credit: NASA, ESA, D. Jewitt (UCLA)

This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image of the asteroid Dimorphos was taken on December 19, 2022, nearly three months after the asteroid was impacted by NASA’s DART mission. Hubble’s sensitivity reveals a few dozen boulders knocked off the asteroid by the force of the collision. Credit: NASA, ESA, D. Jewitt (UCLA)

The central goal of Hera is to fill the gaps in knowledge about Didymos and Dimorphos. Precise measurements of DART's momentum, coupled with a better understanding of the interior structure of the asteroids, will allow future mission planners to know how best to deflect a hazardous object threatening Earth.

"The third part is to generally investigate the two asteroids to know their physical properties, their interior properties, their strength, essentially to be able to extrapolate or to scale the outcome of DART to another impact should we really need it one day," Kueppers said.

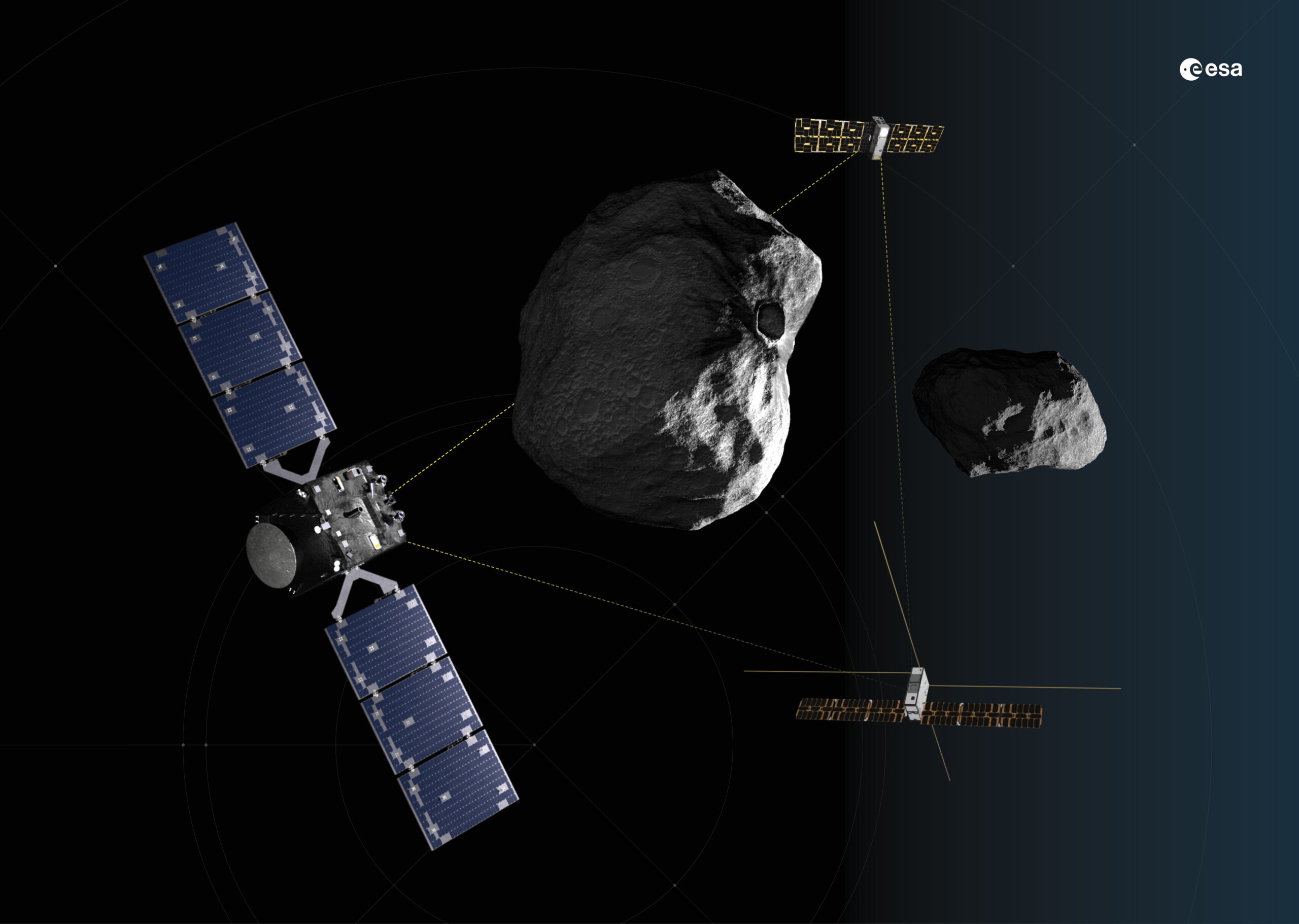

Hera will release two briefcase-size CubeSats, named Juventas and Milani, to work in concert with ESA's mothership. Juventas carries a compact radar to probe the internal structure of the smaller asteroid and will eventually attempt a landing on Dimorphos. Milani will study the mineral composition of individual boulders around DART's impact site.

"This is the first time that we send a spacecraft to a small body, which is actually a multi-satellite system, with one main spacecraft and two CubeSats doing closer proximity operations," Michel said. "This has never been done."

Artist's illustration of the Hera spacecraft with its two deployable CubeSats, Juventas and Milani, in the vicinity of the Didymos binary asteroid system. The CubeSats will communicate with ground teams via radio links with the Hera mothership. Credit: ESA-Science Office

One source of uncertainty, and perhaps worry, about the environment around Didymos and Dimorphos is the status of the debris field observed by Hubble a few months after DART's impact. But this is not likely to be a problem, according to Kueppers.

"I’m not really worried about potential boulders at Didymos," he said, recalling the relative ease with which ESA's Rosetta spacecraft navigated around an active comet from 2014 through 2016.

Ignacio Tanco, ESA's flight director for Hera, doesn't share Kuepper's optimism.

"We didn’t hit the comet with a hammer," said Tanco, who is responsible for keeping the Hera spacecraft safe. "The debris question for me is actually a source of... I wouldn’t say concern, but certainly precaution. It’s something that we’ll need to approach carefully once we get there."

"That’s the difference between an engineer and a scientist," Kuepper joked.

Scientists originally wanted Hera to be in the vicinity of the Didymos binary asteroid system before DART's arrival, allowing it to directly observe the impact and its fallout. But ESA's member states did not approve funding for the Hera mission in time, and the space agency only signed the contract to build the Hera spacecraft in 2020.

ESA first studied a mission like DART and Hera more than 20 years ago, when scientists proposed a mission called Don Quijote to get an asteroid deflection. But other missions took priority in Europe's space program. Now, Hera is on course to write the final chapter of the story of humanity's first planetary defense test.

"This is our contribution of ESA to humanity to help us in the future protect our planet," said Josef Aschbacher, ESA's director general.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/29/625/n/1922564/ec222ac66720ea653c5af3.84880814_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/29/957/n/1922441/c62aba6367215ab0493352.74567072_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2021/07/06/971/n/1922153/7d765d9b60e4d6de38e888.19462749_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/10/29/987/n/49351082/3e0e51c1672164bfe300c1.01385001_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·