Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

Why it matters: The past couple of decades have seen a trend where devices have become harder to repair, thanks to components becoming increasingly complex and companies pulling questionable moves that make fixes difficult. But out in the gritty tech markets of New Delhi, there's a crew of rebel repair shops fighting back by breathing new life into laptops that would've ended up in the scrapyard. Some of these shops in India's capital go as far as creating entirely new machines by stitching together parts from dead machines.

Delhi's Nehru Place is one of the largest commercial centres in the city, and though its significance as a financial centre has declined in recent years, it's still the place to go for "jugadu kaam" – the Hindi equivalent of a "duct tape solution."

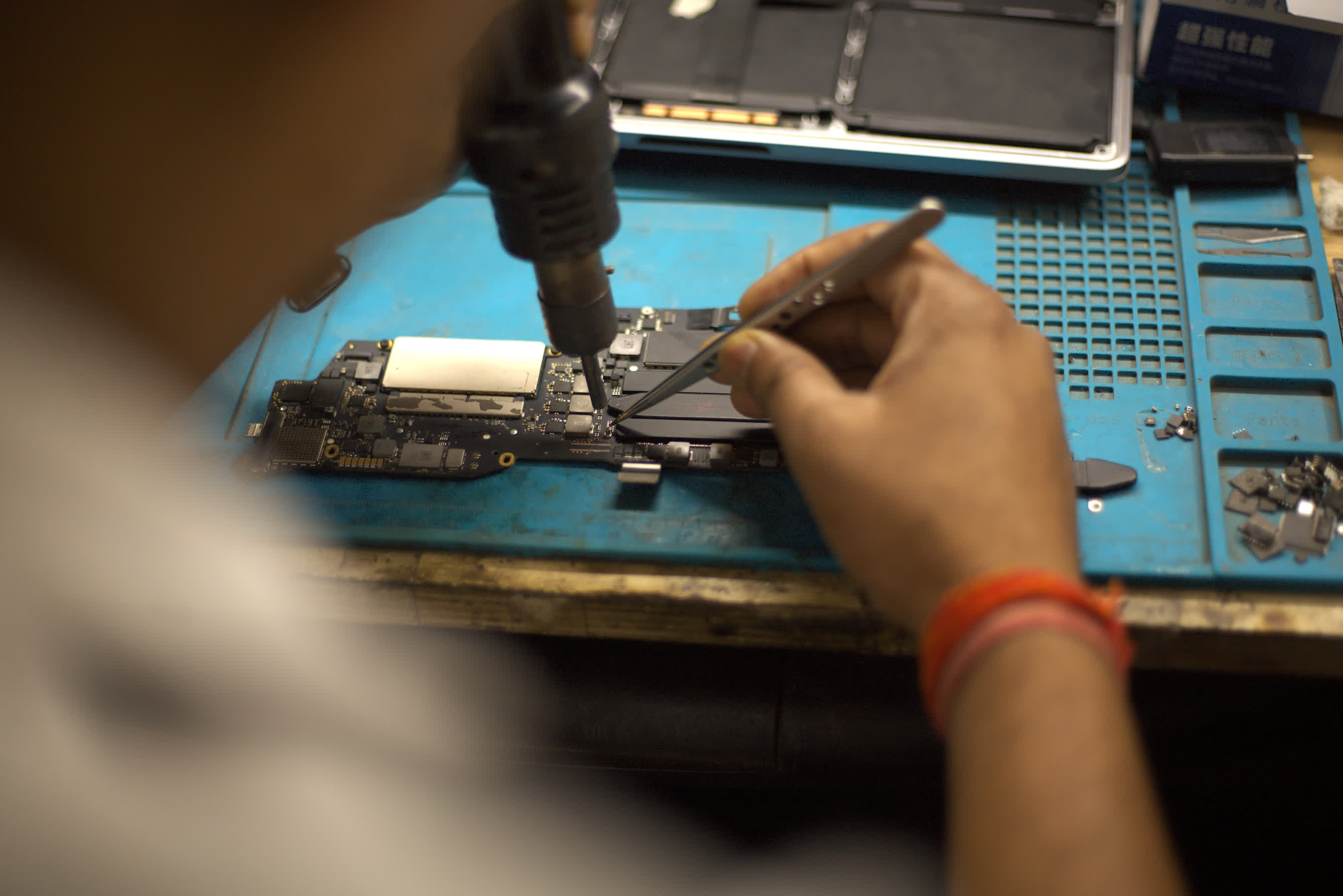

Here, in crammed workshops, technicians are piecing together functioning machines from the guts of various dead and obsolete laptops. They harvest still-viable components from multiple donors and stitch them together.

A report by The Verge describes this phenomenon as one giving rise to "Frankenstein laptops." The publication spoke to several local technicians to understand the process.

"Right now, there is a huge demand for such 'hybrid' laptops," Sushil Prasad, a 35-year-old technician in one of these repair dens, explained. He says most customers just want something that works without emptying their wallets on the latest shiny models.

The resulting creations make computing accessible for students, gig workers, and small businesses who are otherwise priced out. These people normally have to splurge around INR 50,000 (nearly $600) on a new machine, which isn't an option for many. Compare that to your average Franken-laptop that goes for just INR 10,000 (about $110). The difference is all that lies between digital access and being left behind.

Manohar Singh, the owner of the store where Prasad works, recounts the tears of gratitude from one engineering student last year who desperately needed a machine to complete his work. He had saved up for months but was still short of money. Singh put a machine together specially for him from spare parts.

As for how shop owners can create machines over five times cheaper than even a new budget laptop, they source their components from India's vast informal e-waste economies. In areas like Seelampur, one of the country's largest e-waste hubs, an army of informal recyclers comb through hectares of discarded tech daily. They do it to extract reusable components like RAM sticks, slightly faulty motherboards, and rechargeable batteries to supply technicians with what they need.

Sadly, these technicians and shop owners face headwinds from tech titans who seemingly wish to bury the affordable repair movement. Many use restrictive practices like proprietary screws and software locks to deter DIY fixes and force pricey replacements.

Environmentalists argue that formalized right-to-repair rules could help the situation. Advocates like Satish Sinha from Toxics Link NGO believe if repair outfits like Manohar's could legally access OEM parts and training, it would spark a virtuous cycle reducing waste, creating skilled jobs, and democratizing tech access.

"India has always had a repair culture, from fixing old radios to hand-me-down phones. But companies are pushing planned obsolescence, making repairs harder and forcing people to buy new devices instead," Sinha says.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·