QLED TV manufacturers have dug themselves into a hole.

After years of companies promising that their quantum dot light-emitting diode TVs use quantum dots (QDs) to boost color, some industry watchers and consumers have recently started questioning whether QLED TVs use QDs at all. Lawsuits have been filed, accusing companies like TCL of using misleading language about whether their QLED TVs actually use QDs.

In this article, we'll break down why new conspiracy theories about QLED TVs are probably overblown. We'll also explore why misleading marketing from TV brands is responsible for customer doubt and how it all sets a bad precedent for the future of high-end displays, including OLED TVs and monitors.

What QLED TVs are supposed to do

TVs that use QDs are supposed to offer wider color gamuts and improved brightness over their QD-less LCD-LED counterparts. Just ask Samsung, which says that QLED displays deliver “a wider range of colors,” “better color coverage,” and “a brighter picture.” TCL will tell you that its QLED TVs use “billions of Quantum Dot nanocrystals” and deliver “industry-leading color palette and brightness.”

To be clear, properly manufactured QD TVs that use a sufficient quantity of QDs are legit. Excellent examples, which command higher prices than QD-free rivals, successfully deliver bright pictures with wide color gamuts and impressive color volume (the number of colors a TV displays at various levels of brightness). A TV with strong color volume can depict many light and dark shades of green, for example.

Technology reviews site RTINGS, which is known for its in-depth display testing, explains that a TV with good color volume makes "content look more realistic," while "TVs with poor color volume don't show as many details." This is QLED's big selling point. A proper QLED TV can be brighter than an OLED TV and have markedly better color volume than some high-end, non-QD LCD-LED displays.

Let's take a look at some quality QLED TVs for an idea of where the color performance bar should be.

The 2024 Sony Bravia 9, for example, is a $2,500 Mini LED TV with QDs. That’s expensive for a non-OLED TV, but the Bravia 9 covers an impressive 92.35 percent of the DCI-P3 color space, per RTINGS' testing. RTINGS tests color volume by comparing a screen’s Rec. 2020 coverage to a TV with a peak brightness of 10,000 nits. A “good value,” the publication says, is over 30 percent. The Bravia 9 scored 54.4 percent.

Another well-performing QLED TV is the 2024 Hisense U8. The Mini LED TV has 96.27 percent DCI-P3 coverage and 51.9 percent color volume, according to RTINGS.

Even older QLED TVs can impress. The Vizio M Series Quantum from 2020, for example, has 99.18 percent DCI-P3 coverage and 34 percent color volume, per RTINGS’ standards.

These days, TV marketing most frequently mentions QDs to suggest enhanced color, but it’s becoming increasingly apparent that some TVs marketed as using QDs aren’t as colorful as their QLED labels might suggest.

“QLED generally implies superior colors, but some QLED models have been reported to cover less than 90 percent of the DCI-P3 gamut,” Guillaume Chansin, associate director of displays and XR at Counterpoint Research, told Ars Technica.

QD TVs accused of not having QDs

Recently, Samsung shared with Ars testing results from three TVs that TCL markets as QLEDs in the US: the 65Q651G, 65Q681G, and 75Q651G. The TVs have respective MSRPs of $370, $480, and $550 as of this writing.

Again, TCL defines QLED TVs as a “type of LED/LCD that uses quantum dots to create its display.”

“These quantum dots are nano-sized molecules that emit a distinct colored light of their own when exposed to a light source,” TCL says. But the test results shared by Samsung suggest that the TVs in question don’t use cadmium or indium, two types of chemicals employed in QD TVs. (You don’t need both cadmium and indium for a set to be considered a QD TV, and some QD TVs use a combination of cadmium and indium.)

However, per the testing provided by Samsung and conducted by Intertek, a London-headquartered testing and certification company, none of the tested TVs had enough cadmium to be detected at a minimum detection standard of 0.5 mg/kg. They also reportedly lacked sufficient indium for detection at a minimum standard of 2 mg/kg. Intertek is said to have tested each TV set’s optical sheet, diffuser plate, and LED modules, with testing occurring in the US.

When reached for comment about these results, a TCL spokesperson said TCL “cannot comment on specifics due to current litigation” but that it “stands behind [its] high-performance lineup, which provides uncompromised color accuracy.” TCL is facing a class-action complaint about its QLED TVs' performance and use of QDs.

TCL's spokesperson added:

TCL has definitive substantiation for the claims made regarding its QLED televisions and will respond to the litigation in due course. We remain committed to our customers and believe in the premium quality and superior value of our products. In the context of the ongoing litigation, TCL will validate that our industry-leading technologies meet or exceed the high bar that TV viewers have come to expect from us.

“This is not good for the industry”

A manufacturer not telling the truth about QDs in its TVs could be ruinous to its reputation. But a scheme requiring the creation of fake, QD-less films would be expensive—almost as costly as making real QD films, Eric Virey, principal displays analyst at Yole Intelligence, previously told Ars.

What's most likely happening is that the TVs in question do use QDs for color—but they employ cheaper phosphors to do a lot of the heavy lifting, too. However, even that explanation raises questions around the ethics of classifying these TVs as QLED.

Counterpoint's Chansin said that the TCL TV test results that Samsung shared with Ars point to the three TVs using phosphors for color conversion “instead of quantum dots.”

He added:

While products that have trace amounts could be said to "contain" quantum dots, it would be misleading to state that these TVs are enhanced by quantum dot technology. The use of the term "QLED" is somewhat more flexible, as it is a marketing term with no clear definition. In fact, it is not uncommon for a QLED TV to use a combination of quantum dots and phosphors.

Analysts that I spoke with agreed that QD TVs that combine QDs and phosphors are more common among lower-priced TVs with low margins.

"Manufacturers have been trying to lower the concentration of quantum dots to cut costs, but we have now reached undetectable levels of quantum dots," Chansin said. "This is not good for the industry as a whole, and it will undermine consumers' confidence in the products."

Phosphors fostering confusion

TCL TVs' use of phosphors in conjunction with QDs has been documented before. In a 2024 video, Pete Palomaki, owner and chief scientist at QD consultant Palomaki Consulting, pried open TCL’s 55S555, a budget QLED TV from 2022. Palomaki concluded that the TV had QDs incorporated within the diffuser rather than in the standalone optical film. He also determined that a red phosphor called KSF and a green phosphor known as beta sialon contributed to the TV's color.

In his video, Palomaki said, “In the green spectrum, I get about less than 10 percent from the QD and the remaining 90-plus percent from the phosphor.” Palomaki said that about 75 percent of the TV's red reproduction capabilities came from KSF, with the rest attributed to QDs. Palomaki emphasized, though, that his breakdowns don’t account for light recycling in the backlight unit, which would probably “boost up the contribution from the quantum dot.”

Palomaki didn’t clarify how much more QD contribution could be expected and declined to comment on this story.

Another video shows an example of a TCL QLED TV that Palomaki said has phosphors around its LEDs but still uses QDs for the majority of color conversion.

TCL isn’t the only TV brand that relies on phosphors to boost the color capabilities of its QLED TVs— and likely reduce manufacturing costs.

“There is an almost full continuum of TV designs, ranging from using only phosphors to using only QDs, with any type of mix in between,” Virey told Ars.

Even Samsung, the company crying foul over TCL’s lack of detectable QDs, has reportedly used phosphors to handle some of the color work handled entirely by QDs in full QD TVs. In 2023, Palomaki pulled apart a 2019 Samsung QN75Q7DRAF. He reported that the TV's color conversion leverages a “very cheap” phosphor known as yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG), which is “not very good for color gamut."

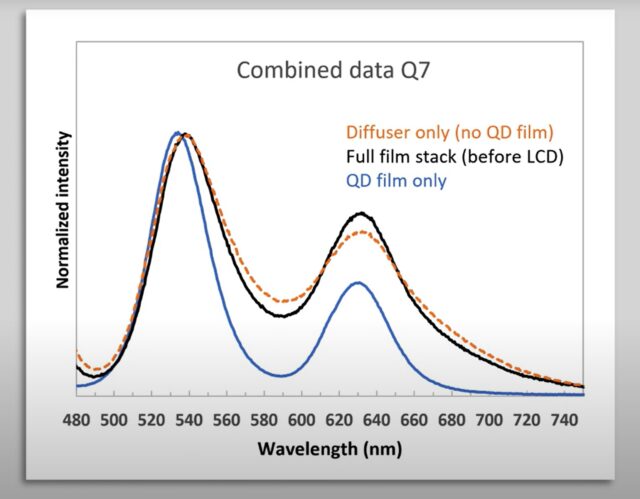

A TV using QDs for color conversion should produce an optical spectrogram with narrow peak widths. As QD supplier Avantama explains, “narrower bandwidths translate to purer colors with higher levels of efficiency and vice versa.” In the QN75Q7DRAF's optical spectrogram that Palomaki provided, you can see that the peaks are sharper and more narrow when measuring the full film stack with the phosphors versus the QD film alone. This helps illustrate the TV's reliance on phosphors to boost color.

Ars asked Samsung to comment on the use of phosphors in its QD TVs, but we didn't receive a response.

TV brands have become accustomed to slapping a QLED label on their TVs and thinking that's sufficient to increase prices. It also appears that TV manufacturers are getting away with cutting back on QDs in exchange for phosphors of various levels of quality and with varied performance implications.

It's a disappointing situation for shoppers who have invested in and relied on QLED TVs for upper-mid-range performance. But it's important to emphasize that the use of phosphors in QD TVs isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

According to Virey:

There are a lot of reasons why display engineers might want to use phosphors in conjunction with QDs. Having phosphors in a QD TV doesn’t necessarily imply low performance. It can provide a little boost in brightness, improve homogeneity, etc. Various types of phosphors can be used for different purpose. Phosphors are found in many high-performance—even flagship—displays.

Virey noted that in cases where QLED TVs appear to have no detectable QD content and sit at the lower end of a manufacturer’s QD TV offerings, “cost is clearly the driver” for using phosphors.

Better testing, please

So why don't TCL and Samsung provide optical spectrograms of the TVs in question to prove whether or not color conversion is occurring as the manufacturer claims? In September, TCL did provide a spectrogram, which it claimed proved the presence of QDs in its TVs. But it’s unclear which model was tested, and the results don’t seem to address red or green. You can view TCL’s spectrogram here.

The company declined to comment on why it hasn't provided more testing results, including for its QLED TVs' color gamut and accuracy. Samsung didn't respond to Ars' request for comment regarding additional testing.

Providing more informative test results would help shoppers better understand what they can expect from a “QLED TV." But that level of detail is absent from recent accusations against—and defenses of—QLED TVs. The type of test results that have been shared, meanwhile, have succeeded in delivering greater shock value.

In the interest of understanding the actual performance of one of the TVs in question, let’s take another look at the TCL 65Q651G that Samsung had Intertek test. The $370 65Q651G is named in litigation accusing TCL of lying about its QLED TVs.

RTINGS measured the TV's DCI-P3 coverage at 88.3 percent and its color volume at 26.3 percent (again, RTINGS considers anything above 30 percent on the latter “good”). Both numbers are steps down from the 99.2 percent DCI-P3 coverage and 34 percent color volume that RTINGS recorded for the 2020 Vizio M Series Quantum. It’s also less impressive than TCL’s QM8, a Mini LED QLED TV currently going for $900. That TV covers 94.59 percent of DCI-P3 and has a color volume of 49.2 percent, per RTINGS’ testing.

Growing suspicion

Perhaps somewhat due to the minimal availability of credible testing results, consumers are increasingly suspicious about their QLED TVs and are taking their concerns to court.

Samsung, seemingly looking to add fuel to the fire surrounding rivals like TCL, told Ars that it used Intertek to test TCL TVs because Intertek has been a “credible resource for quality assurance and testing services for the industry for more than a century.” But another likely reason is the fact that Intertek previously tested three other TCL TVs and concluded that they lacked materials required of QD TVs.

We covered those test results in September. Hansol Chemical, a Seoul-headquartered chemical manufacturer and distributor and Samsung supplier, commissioned the testing of three TCL TVs sold outside of the US: the C755, C655, and C655 Pro. Additionally, Hansol hired Geneva-headquartered testing and certification company SGS. SGS also failed to detect indium, even with a higher minimum detection standard of 5 mg/kg and cadmium in the sets.

It’s important to understand the potential here for bias. Considering its relationship with Samsung and its status as a chaebol, Hansol stands to benefit from discrediting TCL QD TVs. Further, the South Korean government has reportedly shown interest in the global TV market and pushed two other chaebols, Samsung and LG, to collaborate in order to maintain market leadership over increasingly competitive Chinese brands like TCL. Considering Hansol’s ties to Samsung, Samsung’s rivalry with TCL, and the unlikely notion of a company going through the effort of making fake QD films for TVs, it's sensible to be skeptical about the Hansol-commissioned results, as well as the new ones that Samsung supplied.

Still, a lawsuit (PDF) filed on February 11 seeking class-action certification accuses TCL of "marketing its Q651G, Q672G, and A300W televisions as having quantum dot technology when testing of the foregoing models showed that either: (i) the televisions do not have QLED technology, or (ii) that if QLED technology is present, it is not meaningfully contributing to the performance or display of the televisions, meaning that they should not be advertised as QLED televisions.” The complaint is based on the Intertek and SGS testing results provided in September.

Similarly, Hisense is facing a lawsuit accusing it of marketing QD-less TVs as QLED (PDF). "These models include, but are not necessarily limited to, the QD5 series, the QD6 series, QD65 series, the QD7 series, the U7 series, and the U7N series," the lawsuit, which is also seeking class-action certification, says.

Interestingly, the U7N named in the lawsuit is one of the most frequently recommended QLED TVs from reviews websites, including RTINGS, Digital Trends, Tom’s Guide, and Ars sister site Wired. Per RTINGS’ testing, the TV covers 94.14 percent of DCI-P3 and has a color volume of 37 percent. That’s good enough performance for it to be feasible that the U7N uses some QDs, but without further testing, we can’t know how much of its color capabilities are reliant on the technology.

Both of the lawsuits named above lack evidence to prove that the companies are lying about using QDs. But the litigation illustrates growing customer concern about getting duped by QD TV manufacturers. The complaints also bring to light important questions about what sort of performance a product should deliver before it can reasonably wear the QLED label.

A marketing-made mess

While some Arsians may relish digging into the different components and chemicals driving display performance, the average customer doesn’t really care about what’s inside their TV. What actually impacts TV viewers’ lives is image quality and whether or not the TV does what it claims.

LG gives us a good example of QD-related TV marketing that is likely to confuse shoppers and could lead them to buy a TV that doesn’t align with their needs. For years, LG has been promoting TVs that use QNED, which the company says stands for "quantum nano-emitting diode." In marketing materials viewable online, LG says QNED TVs use “tiny particles called quantum dots to enhance colors and brightness on screens.”

It's easy to see the potential for confusion as customers try to digest the TV industry’s alphabet soup, which includes deciphering the difference between the QNED and QLED marketing terms for QD TVs.

But LG made things even more confusing in January when it announced TVs that it calls QNED but which don’t use QDs. Per LG’s announcement of its 2025 QNED Evo lineup, the new TVs use a “new proprietary wide color gamut technology, Dynamic QNED Color Solution, which replaces quantum dots.”

LG claims its Dynamic QNED Color Solution “enables light from the backlight to be expressed in pure colors that are as realistic as they appear to the eye in general life” and that the TVs are “100 percent certified by global testing and certification organization Intertek for Color Volume, measuring a screen’s ability to display the rich colors of original images without distortion.”

But without benchmark results for individual TV models or a full understanding of what a “Dynamic QNED Color Solution” is, LG’s QNED marketing isn’t sufficient for setting realistic expectations for the TV’s performance. And with QNED representing LG’s QD TVs for years, it’s likely that someone will buy a 2025 QNED TV and think that it has QDs.

Performance matters most

What should really matter to a TV viewer is not how many quantum dots a TV has but how strong its image quality is in comparison to the manufacturer’s claims, the TV's price, and the available alternatives. But the industry’s overuse of acronyms using the letter “Q” and terms like “quantum” has made it difficult to tell the performance potential of so-called QD TVs.

The problem has implications beyond the upper-mid range price point of QLED TVs. QDs have become a major selling point in OLED TVs and monitors. QDs are also at the center of one of the most anticipated premium display technologies, QDEL, or quantum dot electroluminescent displays. Confusion around the application and benefits of QDs could detract from high-end displays that truly leverage QDs for impressive results. Worse, the current approach to QD TV marketing could set a precedent for manufacturers to mislead customers while exploiting the growing popularity of QDs in premium displays.

Companies don't necessarily need to start telling us exactly how many QDs are in their QLED TVs. But it shouldn't be too much to ask to get some clarity on the real-life performance we can expect from these devices. And now that the industry has muddied the definition of QLED, some are calling for a cohesive agreement on what a QD TV really is.

“Ultimately, if the industry wants to maintain some credibility behind that label, it will need to agree on some sort of standard and do some serious self-policing,” Yole's Virey said.

For now, a reckoning could be coming for TV brands that are found to manipulate the truth about their TVs’ components and composition. The current lawsuits still need to play out in the courts, but the cases have brought attention to the need for TV brands to be honest about the capabilities of their QD TVs.

Things have escalated to the point where TV brands accuse one another of lying. The TV industry is responsible for creating uncertainty around QDs, and it’s starting to face the consequences.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·