All products featured on WIRED are independently selected by our editors. However, we may receive compensation from retailers and/or from purchases of products through these links. Learn more.

Vibe coding is everywhere, and it’s already drastically changing the tech industry, shaping everything from how software gets made to who gets hired. Back in July, WIRED's very own Lauren Goode went on a journey to become a vibe coder at one of San Francisco’s top startups. In this episode, she sits down with our director of consumer tech and culture, Mike Calore, to share her experience and break down whether vibe coding really spells the end of coding as we know it.

Join us live in San Francisco on September 9th. Get your tickets here.

Mentioned in this episode:

Why Did a $10 Billion Startup Let Me Vibe-Code for Them—and Why Did I Love It? by Lauren Goode

Vibe Coding Is Coming for Engineering Jobs by Will Knight

Cursor’s New Bugbot Is Designed to Save Vibe Coders From Themselves by Lauren Goode

Cheap AI Tools May Come at a Big Long-Term Cost by Paresh Dave

You can follow Michael Calore on Bluesky at @snackfight, Lauren Goode on Bluesky at @laurengoode. Write to us at [email protected].

How to Listen

You can always listen to this week's podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here's how:

If you're on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts and search for “uncanny valley.” We’re on Spotify too.

Transcript

Note: This is an automated transcript, which may contain errors.

Michael Calore: Hey, this is Mike. Before we start, I want to share some exciting news with you. We're doing a live show in San Francisco on September 9th in partnership with the local station KQED. Lauren and I will sit down with our Editor in Chief, Katie Drummond, and we'll have a special guest joining us for a conversation that you will not want to miss. You can use the link in the show notes to grab your ticket and invite a friend. We cannot wait to see you there. Hi, Lauren.

Lauren Goode: Hey, Mike.

Michael Calore: How you doing?

Lauren Goode: I am vibing. How are you doing?

Michael Calore: I'm glad to hear it. You'll be so proud of me for something that I did this weekend.

Lauren Goode: Tell us.

Michael Calore: I used the word compute as a noun.

Lauren Goode: What inspired this momentous occasion?

Michael Calore: I'm so ashamed.

Lauren Goode: Okay.

Michael Calore: But somebody was telling me about their project and I said, "That sounds like it's going to take a lot of compute."

Lauren Goode: You didn't say compute power, you just said compute?

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: And you let it dangle?

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: And, what did they say?

Michael Calore: They agreed, and nodded, and moved on because it's been accepted to use the word compute improperly as a noun. It's short for computing resources or computing power.

Lauren Goode: Yes.

Michael Calore: But all the AI people say compute-

Lauren Goode: Say compute.

Michael Calore: ... as like a thing that exists in the world, which it is not. Computers are things that exist in the world. And what do computers do? They compute. Right? It's a verb.

Lauren Goode: Mike is shaking his fist at the clouds right now.

Michael Calore: I really am.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, but you did it.

Michael Calore: No, I'm not proud of it. It slipped out. It's just because I'm immersed, I'm soaking in Silicon Valley.

Lauren Goode: Why does its usage as a noun bother you so much?

Michael Calore: It's a personal thing, and you can't fight the youth, you can't push back against this big wave of language trend. You just have to accept it, and I'm learning to accept it that people are just using compute, quote, unquote, "improperly," all the time now and it's just part of our lives.

Lauren Goode: First of all, I'm proud of you.

Michael Calore: Thank you.

Lauren Goode: Second of all, if you want to talk about it later, I'm here for you. And third, let's see if we can get through this entire show, in which we are going to be talking about a lot of AI, and not use the word compute as a noun. Do you think we can do it?

Michael Calore: Let's try. This is WIRED's Uncanny Valley, a show about the people, power, and influence of Silicon Valley. Today we're vibing. We're going to talk about vibe coding, basically giving plain language prompts to AI models and letting them do the coding. It's sometimes called AI-assisted code or codegen for code generation, and it's all everyone is talking about in the engineering departments right now. Some tech companies have estimated that 30 to 40% of their code is now written by AI. But what does it look like in practice? Lauren, you now have firsthand experience with this, right?

Lauren Goode: Mm-hmm.

Michael Calore: About a month ago you embedded with a well-known San Francisco based startup that has completely embraced the trend of vibe coding. You asked to join their engineering team, and for some reason they let you.

Lauren Goode: They did. It's still a mystery to me why they said yes, but they did, and I live to tell the tale.

Michael Calore: Are you going to leave us and go become a vibe coder now?

Lauren Goode: Safe to say, not yet, I still love WIRED, I still love journalism. But I did have a really interesting glimpse into the future of work.

Michael Calore: Well, I can't wait to hear all about it.

Lauren Goode: Let's do it.

Michael Calore: I'm Michael Calore, director of Consumer Tech and Culture.

Lauren Goode: I'm Lauren Goode, I'm a senior correspondent.

Michael Calore: So Lauren, take us to the beginning of this reporting assignment for you. What attracted you, not to just look into vibe coding but want to actually try it out yourself?

Lauren Goode: Part of it was curiosity around how tech companies are embracing vibe coding right now and drastically changing their engineering teams, the structure of their engineering teams. How they hire, how they lay off, based on this rise in vibe coding and AI-assisted code. And part of it was my own curiosity around whether my neural pathways could be reorganized in such a way that I could learn something new. I've been doing the same thing in this job here for a long time, you have too, I know. And we're constantly responding to news, reacting, evolving as journalists, but it's different from really having your head deep in the tech space. And I thought, "Well, let me see if I could actually learn this. Supposedly it's really easy now to code because of AI."

Michael Calore: So what was the company where you embedded?

Lauren Goode: It's Notion.

Michael Calore: Okay.

Lauren Goode: Are you familiar with Notion?

Michael Calore: It's a to-do list app?

Lauren Goode: It is, in a sense, a to-do list app, though I'm sure the founders of Notion would describe it as a bit more than that.

Michael Calore: Sorry.

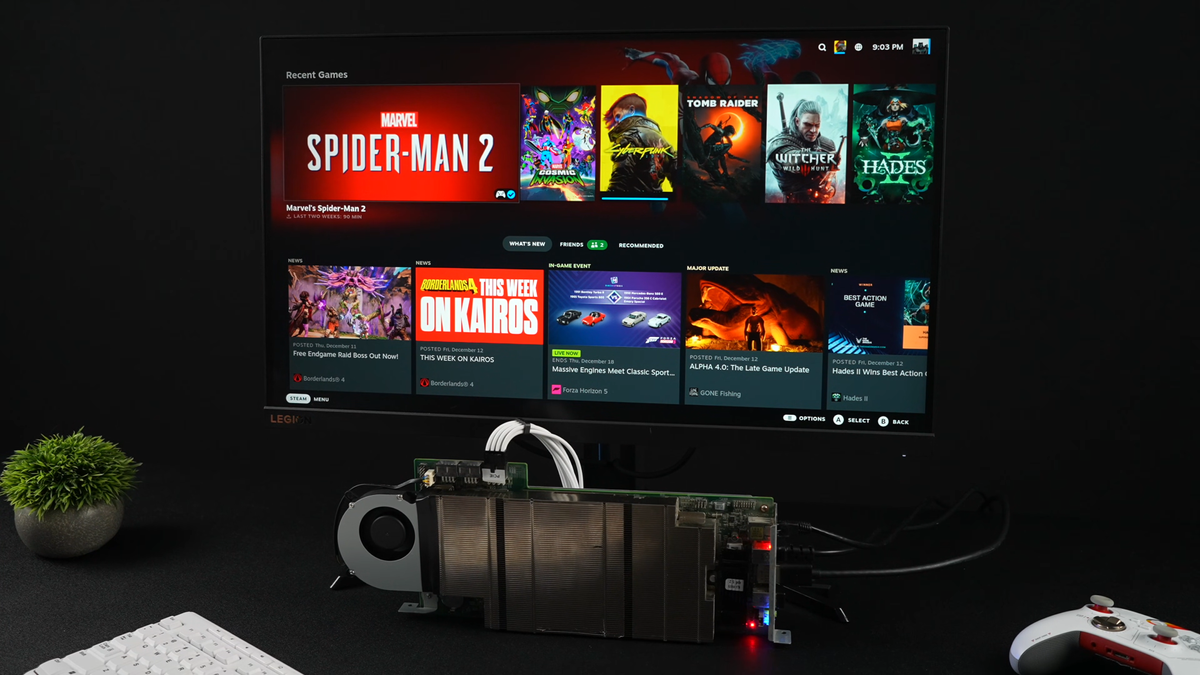

Lauren Goode: Notion is a well-funded startup that's been around since the early 2010s, it has about a thousand employees, it's based in downtown San Francisco. And when the founders originally created Notion, they built it in the idea of this low-code/no-code mindset, which was going to help people code stuff but not have to code. It turns out they were a little early to that, and people just use Notion for to-do lists, templates, diagrams, spreadsheets, that sort of thing. It does have an AI assistant built into it, and now because of the rise of vibe coding, the company is kind of fashioning that AI assistant into something a little bit more agentic. And so they're sort of coming full circle back to this original idea of how can people do low-code/no-code projects in Notion, because we're all vibe coding now. I mean the app itself is a bit of a learning curve. It has about 100 million users, and people are either really into Notion or you just don't really use Notion because you're using Apple Notes or Google Keep, and that's totally fine for you.

Michael Calore: Okay, so they said, "Yes."

Lauren Goode: They, said, "Yes."

Michael Calore: "You can come in-"

Lauren Goode: "And vibe code with us."

Michael Calore: So you went there in July?

Lauren Goode: I did.

Michael Calore: What's Notion as a company, as a workplace, new employee, Lauren Goode?

Lauren Goode: There's this feeling, I know, and I don't have to worry about getting fired either, so I can really say whatever I want. There's this feeling of walking into Notion that feels a little bit like you're in this 2010s time portal of startups. They're in a really nice building downtown. There's a jazz club downstairs. They have a well stocked kitchen, they get lunch delivered every day, there's a Bevi machine. Have you heard of Bevi?

Michael Calore: It's like capital, B-E-V-I?

Lauren Goode: That is correct.

Michael Calore: And it's like mixed sodas, right?

Lauren Goode: Yeah, mixed sodas, yeah. Someone actually coded a little app internally to check which syrups are available for the sodas. It seems like a fairly symbiotic workforce. And they had a desk waiting for me with a tote bag, and stickers, and a welcome note. I had done a little bit of onboarding beforehand, and because they were not going to set me up on my laptop in their IDE, their internal coding tool.

Michael Calore: Smart.

Lauren Goode: They set me up. I was pair programming, so I was paired up with engineers who knew what they were doing.

Michael Calore: What was the first project that you worked on?

Lauren Goode: I worked on something called a Mermaid diagram. It's like basically a type of flow chart that exists within Notion and exists in general. And when you make something in an app and then you want to expand it or zoom into it to look at it more closely, the files that were being generated as Mermaid charts in Notion were static. They were static SVG files and so you couldn't expand them, and it was very annoying for users because they can't actually read the little text that's within this chart.

Michael Calore: Okay.

Lauren Goode: So I did some vibe coding, with two other coders, to make these charts expandable.

Michael Calore: Okay. And so what were the tools that you were using to do the vibe coding?

Lauren Goode: A lot of them use Cursor, which is a well-known AI coding platform. But then within Cursor you select the different AI models that you want to use. In many cases they were using Anthropic's Claude or Claude Code. So you'd go into Cursor, you would choose your model, which I like to say is a Choose Your Player moment.

Michael Calore: So I know this primarily from reading WIRED, but Claude is the preferred model for people doing vibe coding right now? Is that right?

Lauren Goode: It is right now. What's interesting about this is when I was embedded with Notion, it was about a month before OpenAI was announcing GPT‑5, which is supposed to be a coding collaborator, and some people say that OpenAI was taking direct aim at Anthropic's Claude when they did this. Basically there were some model releases earlier this year that really tipped Cursor Code into the category of like, this is legitimately very good for coding.

Michael Calore: Okay, so you've got Cursor, you selected Cursor as your model that you're going to be using, and then what happens? What do you do?

Lauren Goode: Yeah, I mean this is the part where, if you've never coded before and someone gives you an assignment, it's a little bit stultifying because you are like, "Logically, what do I do?" And this is where the pair programming came in handy because I had these experienced coders saying, "Well first, you want to sort of back into the problem. You can use the AI assistant to ask what's wrong with this." And then so we asked, "What's going on with the Mermaid diagrams in this app?" And then once you have an assessment or a diagnosis of what's wrong, you can take that information from the AI, and then craft your prompt for how you want to fix it.

Michael Calore: What did you type in, or what did you say to it, in order to get it working on it?

Lauren Goode: Well, some of this had been pre-written by a Notion engineer, but we then took Claude's notes and we sort of incorporated them into that. And here's basically what I ended up typing into Cursor. First, we created a ticket that said, "Add full-screen/zoom to Mermaid diagrams. Clicking on the diagram should zoom it in full-screen." And then we took some notes from Notion's internal Slack where folks had said, "Mermaid diagrams should be zoom full-screenable just like uploaded pages. They're just SVGs, which is Scalable Vector Graphics. So we can probably go from SVG, to data URL, to image component if we want to zoom." So it was telling Cursor exactly what we wanted and then making a suggestion for how that workflow should go. People have different approaches for how much they want to babysit the AI, but we managed to fix in under 40 minutes, I would say.

Michael Calore: Under 40 minutes?

Lauren Goode: Yeah, combined. And that's actually a feature that ended up going from development, to production, to shipping. So it's working now in Notion.

Michael Calore: Wow. So how did it feel to fix this feature in Notion just by using vibe coding?

Lauren Goode: Honestly, it felt pretty cool. I did feel like I was maybe reorganizing my neural pathways a little bit, learning a little bit more. A few caveats of course, which is then none of the problems we were solving were particularly complex. I was pair programming, so I had much more experienced engineers there with me, basically hand holding. And a lot of what we were working on was front-end stuff, it wasn't going deep into the weeds or the infrastructure and that sort of thing. But I had this moment of feeling a little bit like this anonymous hyperlogical god who is pulling levers and then shipping the thing to 100 million people.

Michael Calore: That's pretty amazing. You have a line in your piece, which I really love, which is, I'm quoting you now, "Time is inversed in the land of vibes. Projects that used to take your whole career are now done in days. While commands you expect to see executed in seconds, take endless minutes." Tell me about this.

Lauren Goode: Well, I guess just if you go back to the earliest days of computing and how long it would take for a computer to do what a computer was doing, which relative to doing it by hand was fast. But then our expectation levels change every time we sort of level up in computing, or like we've talked before about the earliest days of dial-up, which is going away, RIP dial-up, AOL. But it felt endless logging on. But at the same time it was remarkable, you were connecting to all of these people within minutes. And so now with vibe coding, this thing happens where we're very quickly as consumers of technology getting used to using ChatGPT for example, and just getting this reasonable sounding, even if not totally accurate, answer spit out to us in natural language in seconds. When you're vibe coding, you are still seeing the AI assistant take a lot of time to process the code. You're watching lines, and lines, and lines of code stream before you.

Michael Calore: Wow.

Lauren Goode: So it's like a lot of sitting around and waiting, honestly, after you have figured out the prompt. So that's what I mean by this concurrent thing happening where there's a miraculous, almost miraculous feeling, technology happening in front of your eyes, and also you're like, "Well, why isn't it going faster?"

Michael Calore: So aside from that, what else was really surprising about this time you spent at Notion?

Lauren Goode: I think the most surprising thing, after I finished working on a few different features, all in a pair, pair programming, was that I had the chance to actually just talk to the folks there about how they were feeling about this being such a big part of their jobs. And there was some enthusiastic embrace of it, and there was some forced feelings around it like, "This is just the way the industry is going, so we have to embrace it." And I asked people if they felt worried about jobs and one person said to me, "Well, look, it's not as though one coder can now do the job of 100 coders. It's that that one coder is going to become 100 times more productive." Someone else said to me, "Look, when you're working on really complex problems in code, a lot of what you're doing is actually the reasoning, the diagnosis of what's wrong, the planning to fix it, and then maybe 30% of the time is the actual coding." This person also said, "I think that it's going to be a lot of prototyping and rapid coding small fixes that vibe coding is most useful for." So there was this sense from people working there that both, "Well, this is absolutely the future, and we need to adjust our workforce and our workflow, because everyone's going to be vibe coding." But also, "We're still pretty confident that there's going to be a human in the loop."

Michael Calore: Let's take a break right now, and when we come back, Lauren and I are going to break down the ways in which vibe coding has been shaping the tech industry, and whether it really spells the end of coding as we know it. So Lauren, based on what you were telling us about your experience at Notion, where you were able to fix some features on their platform using vibe coding and paired with some engineers, it still feels like what you accomplished in such a short time would've been unthinkable even just two years ago. So, how necessary is it for developers to learn how to code in a traditional way? Is that something that is still encouraged or are people just all in on vibe coding now?

Lauren Goode: I think what we're seeing happen in the talent market at this moment in Silicon Valley, which of course will change three months from now, is that there is this incredibly high demand for people who are really deep in the weeds on AI research. We're seeing this happen with Meta hiring for its Superintelligence Lab, and then OpenAI countering, and then people trying to steal talent from Mira Murati's lab, and it's like this talent war that's happening where people who are deeply steeped in AI are getting offered nine figure salaries. I think that that's not going to go away. The salaries being offered might change, but having real subject matter expertise in programming, software programming, the way it works, I just can't imagine that with the way the world is moving technologically, that that's going to change.

Michael Calore: Right.

Lauren Goode: Then I think, on the other hand, there might be some instances of people who are coming in from different learned disciplines in college or not even having gone to college at all, who are going to take on some of these jobs that are basically handholding for AI. The question for them becomes whether or not they're training AI to eventually replace them.

Michael Calore: Right.

Lauren Goode: There's this middle ground of engineering managers, that I don't really know enough about to say whether or not their jobs are going to be affected by AI, like what that does for the coding industry. But it's a good question. It's certainly something we're watching really closely here at WIRED. That feels like such a cop-out, but it's like I really just don't, I mean, all of this changes so fast.

Michael Calore: Yeah, yeah, and it's hard to say from just spending a week at a company.

Lauren Goode: Exactly. And we'll read reports that say, "Well, consultants' jobs, for example, are on the line because of AI." But then you talk to some people who say, "Yeah, but the AI still is somewhat incompetent at this very specific thing that I do, and you still need a human to oversee that."

Michael Calore: The folks that you worked with at Notion kept referring to them as really good interns.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, interns.

Michael Calore: The AI models and the commands they were sending out, it's like, "They get it mostly right, and it takes them a while, but it helps."

Lauren Goode: Yeah. There was something inherently, a little bit paternalistic about that. And also it was interesting, one of the co-founders who I spoke to, Simon Last, at one point at Notion had been in an engineering managing role, and decided he didn't want to be a manager anymore, so now he's what you'd call a Super IC, a super individual contributor to the technical product. He, at one point, had been using three different vibe coding tools at the same time, and told me, "It just felt like I was managing interns. So now I just stick to just one." So, yeah, the tools themselves, they still need to be watched. Even as they move closer to the buzzword agentic, where they're supposedly just like, you fire them up and let them run. You still need to, I mean, you are writing code that is underpinning your entire product. You need to check on it.

Michael Calore: So on that note, I want to play a clip that we should talk about. This is Dario Amodei, who's the CEO of Anthropic, the company that makes Claude. He said this at an event for the Council on Foreign Relations, back in March of this year.

Dario Amodei [Archival audio]: We are not far from the world, I think we'll be there in three to six months, where AI is writing 90% of the code. And then in 12 months we may be in a world where AI is writing essentially all of the code.

Michael Calore: Okay, let's fact check Dario.

Lauren Goode: When did he say that?

Michael Calore: He said that in March.

Lauren Goode: Okay, so it's been a few months.

Michael Calore: Yeah, it's been close to six months.

Lauren Goode: I don't think it's 90% of the code, based on what we're tracking and what large tech companies like Microsoft and Google have said most recently. It's not at 90% of the code. It could get there. In general, I think what's happening with AI right now, and particularly from some of the frontier model companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, is that its leaders tend to make these statements that I find to be very self-aggrandizing, like "We need to prepare for AGI."

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: And the idea is that they think they're going to attain AGI. AGI is also kind of this, it's hard to define. Some people would posit that we've already achieved that because the AI models are doing reasoning at the level of humans. I think Dario is saying something like, "In six months, 90% of code is going to be written by Anthropic," would obviously be a very beneficial situation for Anthropic because then they would have all these enterprise customers paying for Claude Code, to just run code all day. So they're prognosticating, they're putting themselves out there, but ultimately they see the upside.

Michael Calore: Right. In your experience and from your reporting, not only in this story but other stories about this trend, we're not going to see a bunch of experienced developers retiring right now because they still need to be in the loop. Given that, how is this boom in vibe coding or AI-assisted coding dictating where all the money is going right now in Silicon Valley?

Lauren Goode: Oh, it's affecting a lot. I think right now what's happening broadly in AI investing, is that investors are looking closely at whether or not a company is just kind of like a wrapper. They build some feature on top of other AI models, and then that little startup has to pay for access to those models and also try to lure in customers, and it becomes this really hard balance. But I think that there are other startups like Cursor for example, which is made by a company called Anysphere, has raised I think $900 million from Andreessen Horowitz, Thrive Capital. It has a bunch of big clients like Notion obviously, but OpenAI, Instacart, Midjourney, Discord, I think even Sundar Pichai said something once about how he's been playing around with Cursor. It's become a little bit of the Kleenex of IDE right now, like everyone's talking about using Cursor when they're talking about vibe coding. I think a lot of investors are seeing value in a service like that, that has gained this user base and mindshare early on, and it's providing a development platform just for vibe coding.

Michael Calore: All right, so if everybody's vibe coding and not everybody is experienced enough to know whether or not the output is quality, what does that mean for the software that we're all using? Are companies shipping bad code because they're just vibe coding everything and they don't have the people to, quote, unquote, "monitor the interns, babysit the AI"?

Lauren Goode: Yeah, right. Are you asking if I shipped bad code, Mike? Because the answer is, "Absolutely yes."

Michael Calore: I would never, I would never.

Lauren Goode: So I asked Ivan Zhao, who is the co-founder and CEO of Notion, I asked him a couple different ways, so he had a couple different answers. One of his answers was, "Good and bad quality is subjective in code. If the code is correct, it runs. If it's bad or incorrect, it's not going to work. It's different from you or I writing a story, which of course has to be correct as well, but someone could look at the way we structure a sentence or have written a feature story for WIRED and say, 'That was good or bad.' With code, it's sort of like, the end game is that it has to work, it has to run." And I kept pressing though, "But isn't there this degradation of quality of code over time, particularly if the inputs are bad and then eventually the AI outputs are bad?" And he said, "Well, Simon will just build a tool that helps us track that before it ships." So it was funny because it was putting a human back in the loop again.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: I think also long-term is a concern. If you have a high turnover rate of engineers in your staff, and two years from now it's a whole new team of engineers who are looking at this codebase that was vibe coded by an associate level engineer and trying to solve a problem in the code base, then I could see how that could potentially be a problem. You'd really want just the code to continue to be high quality because your team's going to have to refer to it for years to come.

Michael Calore: Mm-hmm.

Lauren Goode: It's like an archive and you want in general with archiving anything, you want it to be as high quality as possible.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: Mike, I'm curious, have you done any vibe coding?

Michael Calore: I hesitate to call it vibe coding, but I have done some vibe music making.

Lauren Goode: What is that like?

Michael Calore: So there's all these generative music tools that exist, where you can give the system very vague instructions about what you want, and then it generates music based on your instructions. And you actually make the sounds, but you don't pick the order, or the melody, or the tempo, or anything like that. When you want to adjust it, you can tell the system, "I would like this 10 BPM faster. I would like half as many notes. I would like this to be in F-sharp minor." And then it just makes a song. So I've done some of that.

Lauren Goode: What app are you using?

Michael Calore: Well, I would recommend, for people who are just getting started, to try the Bloom Pack, which is something that my close personal friend Brian Eno put out many, many years ago at the dawn of the mobile touchscreen era, that he and his technology partners have been updating. And now you can get a bunch of different music-making apps that are purely generative that just rely on touchscreen input. So I think you can get all of the Bloom variations for under $10 on the App Store.

Lauren Goode: Do you have any interest in trying to vibe code, like an app?

Michael Calore: Sure. Not right now, I'm just too busy.

Lauren Goode: Sure.

Michael Calore: I mean, it's interesting. I think anybody who's listened to us talk about it is like, "Okay, so I can make an app? And is that possible? Can I just download Cursor and make an app?"

Lauren Goode: Cursor is a little bit more advanced. What I hear from people, including our colleague Will Knight who's been vibe coding some stuff with his son, Replit and Lovable are a little bit more user-friendly.

Michael Calore: Okay.

Lauren Goode: But yeah, you're not only writing the code, but then you need to run it somewhere. You need to give it a container or a site to run on. And then it's also like, "Is this actually a value-add? Does this really do anything?" I tried to create some kind of plugin essentially, that would autosave PDFs for me from certain research websites I was reading. And then I was like, "There are so many Clipper tools and plugins that already do this."

Michael Calore: Okay.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. But yeah, I'd be curious to see what you come up with.

Michael Calore: Okay.

Lauren Goode: In fact, I'm probably going to quiz you about it on an upcoming show. So this is an official, this is your vibe coding assignment.

Michael Calore: All right. I've better roll up my sleeves and get cracking.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, you get pair programming,

Michael Calore: Get vibing.

Lauren Goode: Get vibing, get your Bevi, and your Celsius, and your ZYN ready to go, and your crew neck sweatshirt.

Michael Calore: And my dog at my feet. All right, let's take another break, and we'll come right back and do recommendations. Welcome back. Lauren, thank you for bringing us your vibe coding reporting onto the pod today. But now it is time to get personal and have you tell our listeners your recommendation.

Lauren Goode: You really set that up like I was going to say something hyper-personal. This is not that. My recommendation is a type of jam. This would go very nicely with Katie's butter obsession. It is Harrods. Is that how you say that?

Michael Calore: Harrods, like the department story?

Lauren Goode: Yes. There are a couple different kinds that I really like. One is a Harrods raspberry low sugar jam, I think, and the other one is a damson plum jam. They're both great. I have a friend who has been flying back and forth a lot between London and here in the US lately, who often brings me a jar of this jam, and it is just chef's kiss. It is so good. There's also a new shop in my neighborhood, I don't know if you've been there yet, that makes really, really good English muffins, like fresh English muffins, no preservatives. I go on the weekends and buy a bunch and then freeze them.

Michael Calore: Is there a line?

Lauren Goode: No, there isn't much of a line.

Michael Calore: Oh, okay. Then I'll-

Lauren Goode: It's called Leadbetter's. Shout out to Leadbetter's.

Michael Calore: All right, I'll check it out.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, totally check it out. And they have all their kinds of really good sweets too, breads and whatnot. But in the morning now I use some butter, it's not French butter, I got to pick some of that up, and this jam. And it's the perfect way to start the morning.

Michael Calore: Okay, so what sets this jam apart from all the other jams that are on the shelf at my hippie grocery co-op?

Lauren Goode: That it flew like 6,000 miles, obviously.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: No, it's just, I don't know, it's very good. It's a really good jam.

Michael Calore: Reason enough to recommend it.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, I love it.

Michael Calore: Great.

Lauren Goode: So, if anyone's flying back and forth, pick me up some Harrods Jam please. What's your recommendation?

Michael Calore: There's a new game in the New York Times app.

Lauren Goode: Okay.

Michael Calore: And I've been playing it for a couple of days, and I'm already completely obsessed, and I just want more, it's called Pips.

Lauren Goode: Pips?

Michael Calore: P-I-P-S.

Lauren Goode: Okay. And what does it do?

Michael Calore: It's a puzzle game, obviously.

Lauren Goode: Who is your daddy and what does he do?

Michael Calore: My daddy is the New York Times Games app. So you use dominoes, and the dominoes all have different numbers on them, and you have to place the dominoes onto a playing board that has rules about how many numbers there can be in certain sections. So it's like a logic game. It's very hard to describe, but if you open it up and follow the tutorial, it'll take you 10 seconds to figure it out. And then it'll take you minutes to figure out how to solve the hardest boards. So it's very challenging, which is why I like it. And it gives you three levels to play every day, so you can play easy, medium, and hard. Which is awesome, because it's like three games in one. And yeah, it's super great. I immediately was just like, "I want more of this."

Lauren Goode: That sounds really fun.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: I'm surprised you're not playing a words-based game, but you've got plenty of those.

Michael Calore: Oh, yeah, sure. There's words games to play until the end of humanity, I'm sure. But this game is a little bit more fun because you can play it while you're listening to a podcast, or while you're watching television, if you're the type of person who's a two screen individual-

Lauren Goode: I think we all are.

Michael Calore: ... on the couch.

Lauren Goode: Yeah, we all are.

Michael Calore: So it's a little less language part of the brain intensive, but still brain intensive.

Lauren Goode: Nice.

Michael Calore: Yeah, so I dig it. Pips.

Lauren Goode: Wow. Single-handedly saving journalism, the New York Times games section.

Michael Calore: Get your Pips on, folks.

Lauren Goode: Get your Pips on. It's a fun name too. Hope you have some jam with your Pips and your vibes.

Michael Calore: The best jam.

Lauren Goode: Yeah.

Michael Calore: The London jam.

Lauren Goode: Good vibes.

Michael Calore: All right, that's our show for this week. Thank you for listening again to Uncanny Valley. If you like what you heard today, make sure to follow our show and rate it on your podcast app of choice. If you'd like to get in touch with us with any questions, comments, or show suggestions, you can vibe, write to us at [email protected]. Today's show is produced by Adriana Tapia and Mark Lyda. Amar Lal at Macro Sound mixed this episode. Mark Lyda is our San Francisco studio engineer. Sam Spengler fact-checked this episode. Kate Osborn is our executive producer. Katie Drummond is WIRED's global editorial director, and Chris Bannon is Condé Nast's head of Global Audio.

3 months ago

27

3 months ago

27

English (US) ·

English (US) ·