“Are you not entertained?” bellowed Russell Crowe over the bodies of half a dozen or so armoured combatants in the original Gladiator. It’s a line etched in our collective memory. It also sums up Ridley Scott’s belligerent and punchy directorial approach to this brawny, businesslike sequel. Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since the first film scooped five Oscars in 2001 (including best picture and best actor for Crowe), but what’s notable is how little has changed. Admittedly there’s a splatter of fresh blood. Gladiator II passes the tunic and battle sandals to Paul Mescal, as enslaved but noble warrior Lucius. It sees Denzel Washington sink his teeth into a peach of a role as the slippery, ambitious master of gladiators, Macrinus, and ramps up the spectacle (and, it has to be said, the silliness) with sharks in the Colosseum, an attack rhino and a terrifying CGI hell-creature that seems to be part shaved baboon, part demon. Yes, we are entertained, how could we not be? But, sharks and rhino aside, fresh ideas are conspicuously missing. This sequel is so derivative of its predecessor, it’s practically a remake.

This is evident from the outset. Gladiator and Gladiator II both open with a shot of a manly hand fondling grain. In the first movie it’s the Malickian image of Crowe’s meaty paw running through a field of golden wheat; in the second, it’s Mescal pensively toying with some chicken feed. The symbolism is clear: they might be fearsome soldiers, but these are solid, simple men, anchored to the earth. The two share more than a fondness for cereal crops: both suffer from a near identical double-whammy of inciting incidents early on. Both lose loved ones, and find themselves enslaved by the Roman empire, subsequently channelling their grief and rage into gladiatorial combat. They even share a trademark move: a scissoring two-sword decapitation that serves as an emphatic final word in most disagreements.

The same paradoxical truths grapple at the heart of both pictures, which argue that the gladiatorial “games” – days of slaughter for the entertainment of the masses – represent everything rotten at the core of ancient Rome. Cruel and fickle leaders – in this case the tittering, quixotic double act of brother emperors Caracalla (Fred Hechinger) and Geta (Joseph Quinn) – use them as a distraction from the grim realities of life for the average Roman, and as a convenient way to dispose of enemies. At the same time, the violence and savagery is rather the point of the Gladiator movies. The visceral combat sequences are phenomenal – superbly choreographed, formidably executed and edited with switchblade precision. Sure, Scott can dress it all up in a cloak of honour and dignity, but ultimately, the Gladiator movies tap into just the kind of primal bloodlust that whips the Colosseum audience into a baying frenzy.

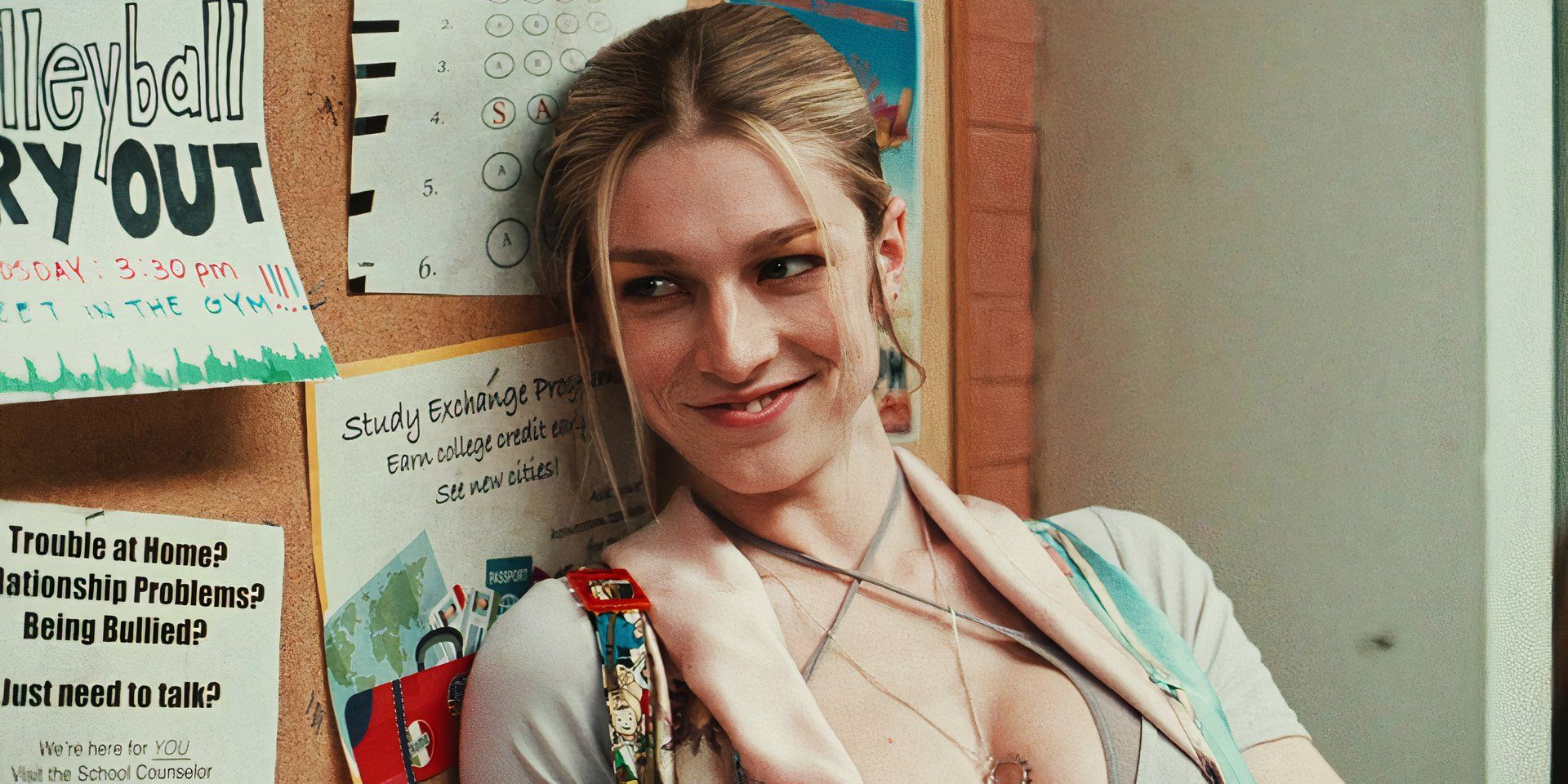

It’s for this reason that Gladiator II is quite binary and schematic in its approach to good versus evil. In the latter camp, the emperor brothers are enjoyably ghastly. Caracalla has a pet monkey, an advanced case of syphilis and the high, giddy laugh of a spiteful child. Geta is smarter, more calculating and vengeful, and wears so much fright-mask makeup that he starts to resemble Bette Davis in What Ever Happened To Baby Jane?. On the side of honour and virtue we have Lucius, essentially a cut-and-paste version of Crowe’s Maximus, with added angst. Mescal acquits himself well in the action, and brings a wincing, grimacing base note of despair to his righteous rage. But he’s an actor who works best when he is excavating the tiny, textured details of a character, and this is a role that requires a more broad-shouldered and muscular approach. Crowe’s bullish, brawling line readings from the first film are much missed here. The only returning main character, Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) has been stripped of much of her minxy complexity and now champions, rather blandly, the egalitarian vision of Rome dreamed of by her father, the emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Thank goodness, then, for Washington, delivering by far the most chewy and memorable performance as canny social climber Macrinus. The former slave is a slippery, ambivalent character who acts as mentor and supporter to Lucius, but whose motives in this, as in all things, are entirely self-interested. If we are entertained, it’s not because of the sharks or the apes chowing down on the supporting cast, but because of Washington gnawing chunks out of the scenery every time he’s in shot.

-

In UK and Irish cinemas

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/11/15/862/n/1922153/911b7d1c6737a4111b6008.57513343_.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·