Many stories have been told about an ancient power that tried to conquer the world, only to be punished for its hubris and vanish. This power wasn't Atlantis – it was Atari.

Following the home version of arcade sensation Pong, the Atari 2600 became a cornerstone of the second generation of gaming consoles. With replaceable cartridges and a programmable CPU instead of hardwired transistors, it aimed to bring the arcade experience into the home – and succeeded, becoming the first game console owned by millions.

The Atari 2600's downfall was just as spectacular as its rise. In Japan, it became known as the "Atari shock." In the U.S., it was called the video game crash. Despite this, the 2600 survived and remained on the market into the 1990s, competing with Nintendo until newer players took its place.

Image credit: darkrisingmitch

The Rise of 1D Graphics

When Atari began working on Project Stella in 1975, there was little to compare it to. The company quickly realized that the biggest obstacle to affordability was the high cost of RAM at the time. The Fairchild Channel F, which beat Atari to market, had 2KB of VRAM – enough for a 104 x 60 resolution and four colors across the entire screen.

Atari hired Jay Miner to develop the console's Television Interface Adaptor (TIA), which would render graphics line by line, allowing for 160 pixels per line and up to 192 lines per frame. Each line was limited to four colors and five non-identical objects.

Games like Video Chess used clever techniques to avoid drawing many different objects on the exact same line:

Unlike today's dot-matrix displays, which can refresh a full frame at once, CRT televisions of the era drew pixels one at a time. The TIA used 20 bits of register memory to render a blocky, two-color background on one side of the screen, then mirrored or duplicated it on the other – unless instructed otherwise while the line was being drawn.

The 2600 was so underpowered that it couldn't even hold a full game screen in memory. Developers had to draw the screen line by line, in real time, as it was being sent to the TV. That meant perfect timing down to the microsecond, or the display would break. Devs called this technique "racing the beam."

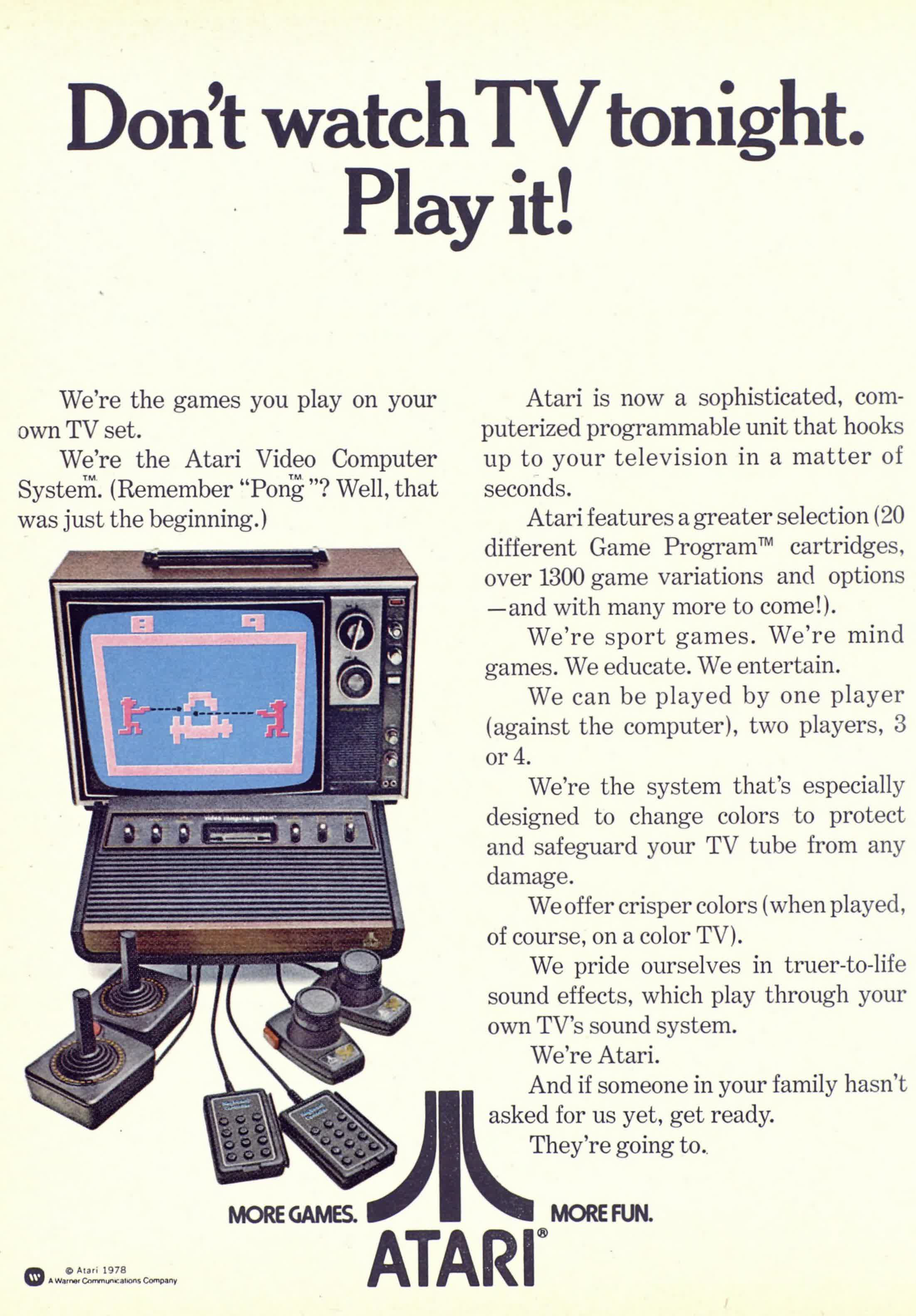

Warner Communications acquired Atari in 1976, accelerating development. The following year, the Atari Video Computer System (VCS) launched at $190 (about $1,000 today). The console was bundled with three controllers: one 8-direction joystick and two rotary paddles, each with a single action button.

Internally, the Atari 2600 was nicknamed "Stella," after the bicycle owned by one of the engineers. The name stuck with the development team long before the console was officially branded as the Atari VCS. "Stella" lives on today as the name of a popular emulator and a nostalgic reference among retro gaming fans.

At first, the console's sales did not impress. Atari didn't yet have the game library to justify the cost. The pack-in game was Combat, based on the arcade hit Tank. That game didn't fully utilize the console's capabilities, using the same four colors for all lines. Even celebrity endorsements from Pelé, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Pete Rose didn't boost early sales much.

The console's first killer app was Space Invaders, released in 1980. With an all-black background and rows of identical enemies, it held up surprisingly well against its arcade counterpart.

Space Invaders was the first officially licensed arcade port for a home console. Its success quadrupled Atari 2600 sales practically overnight – people bought the console just to play that game. It set the standard for using hit arcade titles to drive home console adoption. Over time, it sold more than six million units.

A wave of pixelated aliens descends in Space Invaders on the Atari 2600 – gaming's first killer app that helped launch the home console revolution.

Atari went from a $75 million company to a $2 billion empire in just a few years. During this explosive growth, the company developed a reputation for being both brilliant and wildly unprofessional.

Atari's headquarters were infamous for hot tubs, booze-fueled meetings, impromptu parties, and even open drug use. At one point, founder Nolan Bushnell installed a hot tub on-site, and stories of poker games in the office only added to the company's mythos.

The First "Easter Egg"

One of the most iconic stories from the Atari 2600 era is about the game Adventure, released in 1980. The game's creator, Warren Robinett, was frustrated that Atari didn't credit developers for their work. So he secretly added a hidden room that displayed the message:

"Created by Warren Robinett"

While hidden features had appeared in earlier games – dating back to the 1973 video game Moonlander – Adventure is notable for being the first instance where such a hidden message was referred to as an "Easter egg."

The term was coined by Steve Wright, Atari's Director of Software Development, who likened the experience to a traditional Easter egg hunt.

Robinett kept the secret for over a year, hiding it even from other Atari employees. The company only discovered the hidden message after players uncovered it post-release. Rather than remove it, Atari embraced the idea, and Easter eggs soon became a fun and beloved tradition in the gaming world.

The First Third-Party Studio

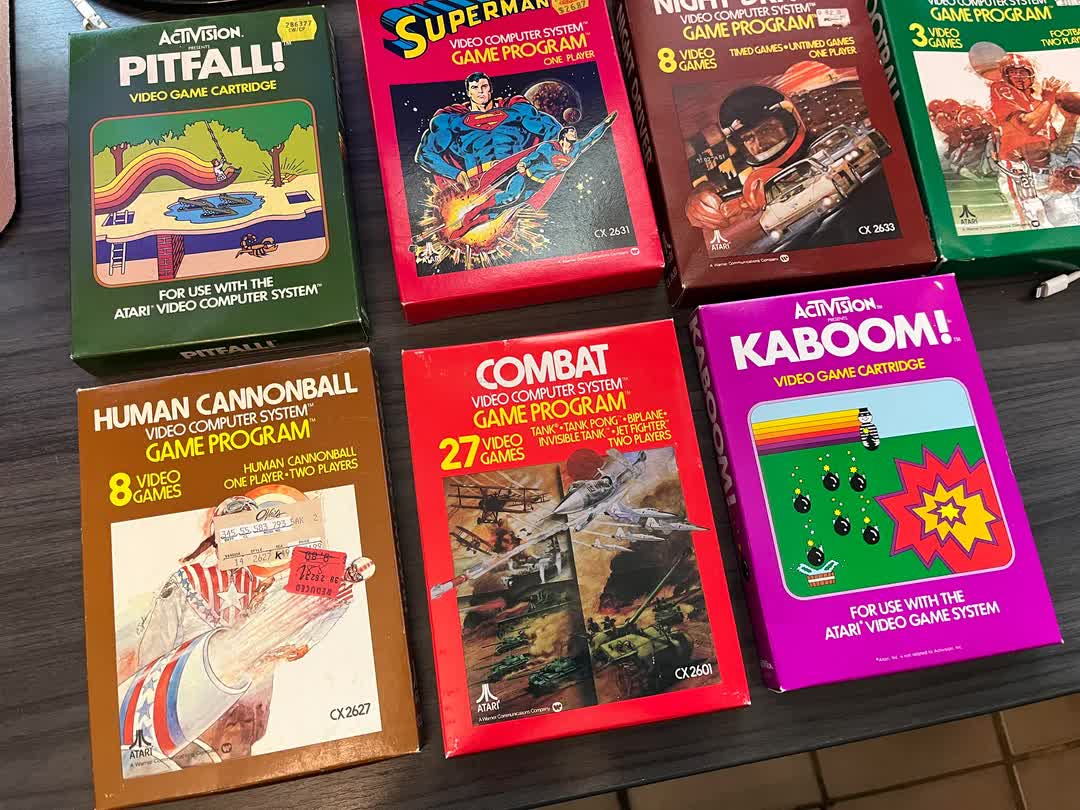

Image credit: MasonJarring

Four programmers at Atari were known as the "Fantastic Four": David Crane, Alan Miller, Bob Whitehead, and Larry Kaplan. They were responsible for some of Atari's most critically acclaimed games, as well as the operating system for the company's upcoming line of home computers. Yet, they received no public credit for their work – and no royalties from the sales of the games they developed.

An internal memo circulated to Atari programmers in early 1979 revealed that the games created by the four accounted for 60% of Atari's total game sales. Miller drafted a proposal inspired by standard practices in the music industry (in which Warner, Atari's parent company, was involved), and the group presented it to Atari's new CEO, Ray Kassar.

Kassar threw the four out of his office, famously saying they were "no more important than the guy on the assembly line who puts the cartridges together." The CEO failed to acknowledge the difference between the importance of a job and the value of the person doing it.

Image credit: MasonJarring

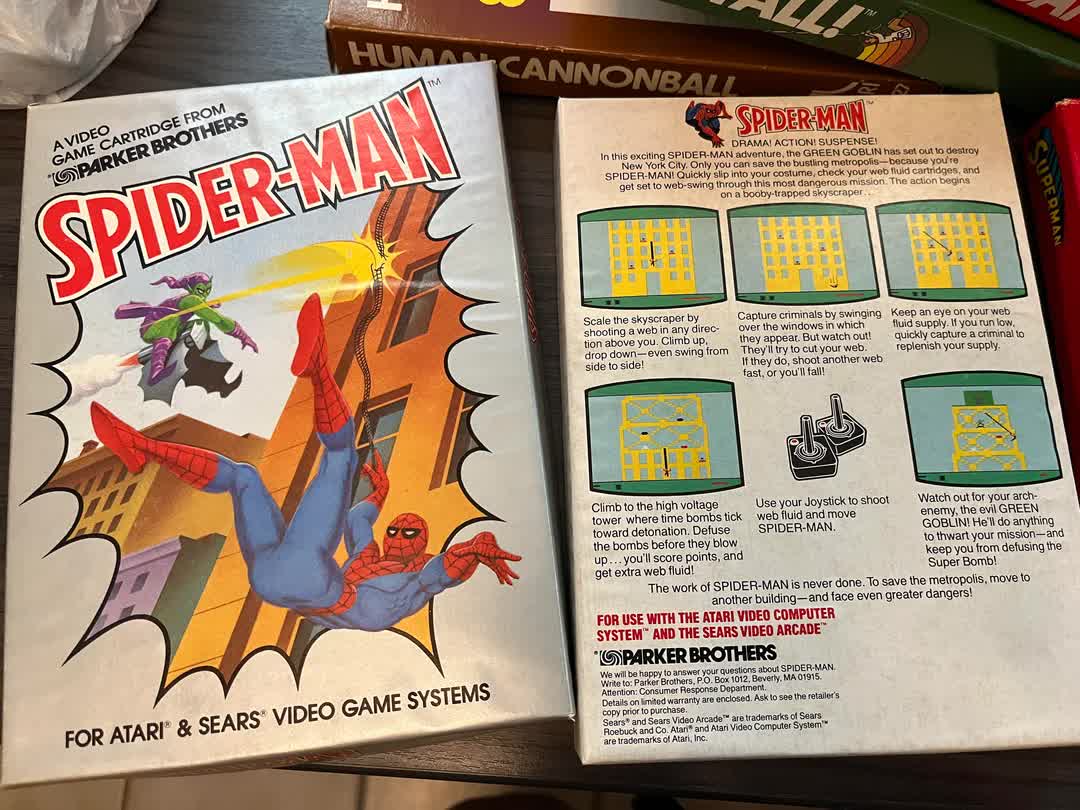

Together with businessman Jim Levy, the four decided to found their own company to develop games for the VCS. In this new studio, programmers would receive royalties and even a dedicated page about them in the game manual. They initially called themselves "VSync," but realizing the term wasn't widely understood by the public, they changed the name to Activision.

Activision's best-selling title for the VCS was Pitfall! – an endless platformer that used pseudo-random number generation to create the same level layout for every player.

A classic moment from Pitfall! on the Atari 2600 – players swing over crocodile-infested pits in one of the earliest and most iconic platformers in gaming history.

Activision eventually became one of the largest third-party publishers in the world, with franchises like Call of Duty, Tony Hawk, and Crash Bandicoot under its belt. The company underwent several transformations, first through the Activision Blizzard merger, and later by becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of Microsoft's gaming division.

Atari sued Activision in 1980, but the case was settled within two years. As part of the settlement, Activision agreed to pay royalties to Atari. This resolution set a precedent that allowed dozens of other companies to begin developing games for the VCS.

In gaming's early days, experienced developers were rare by definition – the industry itself was brand new. Many early games were created by pioneers who were learning as they went: electrical engineers, comp sci geeks, hackers, and tinkerers exploring uncharted territory. They may have lacked formal training in game design, but they made up for it with raw creativity, technical ingenuity, and a willingness to invent the rules as they went.

Before the Internet, it could take weeks between the launch of a game and its first reviews in game magazines, which most people weren't subscribed to anyway. When seeing a game on the shelf, most people had no way to know whether it was any good. This situation could actually benefit Atari as long as the quality of its own games remained consistent.

Well… about that.

Hubris Leads to Sinking

Image credit: DrAg0r

The new arcade sensation Pac-Man was released for the VCS in 1982, replacing Combat as the console's pack-in game. Atari was confident that the entire game – including a two-player mode – could fit on a standard 4KB ROM chip.

To prevent the ghosts from appearing on the same scanline, they were programmed to flicker constantly, ensuring they never appeared in the same frame. The game featured only one maze, and the sound effects were greatly inferior to those of the arcade version. Ms. Pac-Man, released the following year on an 8KB cartridge, was tragic proof that it could have been done much better.

The Atari 2600 had only 128 bytes of RAM, and cartridges were initially limited to 4KB of ROM. Developers soon discovered a technique called "bank switching," which allowed cartridges to swap between multiple 4KB banks of code, effectively expanding the game's size without changing the hardware. This trick enabled increasingly complex games like Pitfall! and River Raid.

Later in 1982, E.T. became the most successful movie of all time. Warner CEO Steve Ross began negotiations with Steven Spielberg and Universal Studios to release a video game adaptation in time for the holiday season. Developer Howard Scott Warshaw was given just five weeks to create it.

The result? Not as bad as you might expect. The game was simplistic and flawed in several ways, but it was fully functional. Reviews at the time were largely positive. So why is it now considered one of the worst games ever made?

First, it was basically unplayable without reading the manual first. The graphics often clashed with gameplay logic – E.T. could fall into pits even if only his head was over them, while his feet were visibly on solid ground. The game may have been an example of a game that was critically acceptable but not commercially successful. In short: it just wasn't fun.

Atari made 5 million E.T. cartridges, but most went unsold or were returned. At the time, rumors swirled that unsold copies had been buried in a landfill in New Mexico and covered in concrete. Like many extraordinary stories, it was dismissed as a myth – until 2014, when a dig at the site confirmed the burial of E.T. and other Atari games.

The VCS was officially renamed the Atari 2600 with the launch of the Atari 5200, which coincided with the release of E.T.

The 5200 became a case study in how not to design a "Pro" version: it was essentially a home computer, but it lacked compatibility with both Atari's earlier consoles and its actual home computers. Its analog joystick didn't automatically return to center, making it deceptively hard to stop moving in games. The 5200 was discontinued in 1984.

Savior Over the Ocean

The Atari 2600 "Darth Vader" edition, released in 1982, is a special version of the classic console featuring an all-black, design reminiscent of Vader's iconic helmet from Star Wars. It was also the first model to be officially branded as the Atari 2600, dropping the VCS branding. Image: renatobara

Atari lost $538 million in 1983, compared to a $300 million profit the previous year. In 1984, the company's home division was sold to someone who knew a thing or two about overcoming adversity: Holocaust survivor and Commodore founder Jack Tramiel.

The new owner believed dedicated consoles were merely a temporary stopgap and canceled the launch of the Atari 7800, a true successor to the 2600.

Having sold millions of units of the FamiCom console in Japan, Nintendo released it in the US in 1985 under the name Nintendo Entertainment System. Nintendo was careful to avoid using the word "console" in its marketing, branding its cartridges as Game Paks.

More significantly, it introduced a lock-out system to prevent third-party publishers from releasing games without Nintendo's approval. Within a year, dedicated consoles became desirable again.

A rainbow-striped Atari 2600 Jr. sits ready with Dig Dug loaded.

The Atari 7800 was finally released in 1986, but it may have been too late. For backward compatibility with the 2600, it retained the same TIA chip. To reduce costs, it used that chip for audio as well – giving the system dated-sounding audio compared to its competition.

Around the same time, a redesigned version of the 2600 – nicknamed the 2600 Jr. – was launched at a $50 price point, accompanied by the slogan: "The fun is back!"

The Atari 800XL, part of Atari's 8-bit home computer line, combined gaming and productivity in the early 1980s – featuring built-in BASIC, a full keyboard, and compatibility with Atari 2600 peripherals.

By 1991, the market has moved on to the Sega Genesis and Super NES. The Atari 2600 was discontinued on the first day of 1992, along with the rest of Atari's 8-bit home catalog. In its lifetime, the 2600 sold over 30 million units.

Retro versions of the console have been released since the early 2000s. The Atari VCS (2021) includes 100 built-in games, while the Atari 2600+ (2023) and 7800+ (2024) brought back support for original Atari 2600 and 7800 cartridges.

The Atari 1040ST was a powerful 16-bit home computer from the mid-1980s, known for its built-in MIDI ports, making it a favorite among musicians and a rival to early Macintosh and Amiga systems.

The Atari 2600 brought video gaming into millions of homes, though arguably that would have happened anyway years later thanks to home computers. Atari's more enduring legacy was proving that dedicated game consoles could be compact, affordable, and easy to use. That legacy lasted for decades, with home consoles only adding a hard disk in the early 2000s.

In the past two decades, gaming consoles have grown increasingly similar to gaming PCs, offering more features but at the expense of simplicity. Still, millions of gamers fondly remember the days of inserting a cartridge and playing instantly – no updates, no installs, just fun.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·