Across its two seasons, it became common to describe Andor as “unlike Star Wars.” Typically a compliment, this phrase was an easy shorthand to use, and it’s taken on greater meaning now that its cast and creatives can speak more freely about what stayed on the cutting room floor.

Creator Tony Gilroy has recently discussed his active choice to not have the show feature future key players like Palpatine, Darth Vader, or Rogue One protagonist Jyn Erso. Ultimately, he thought including any of the three would’ve been unnecessary or overindulgent and in Jyn’s case, “disrespectful” to her original appearance. It’s a surprising level of restraint that Star Wars hasn’t always been the best at exercising, and despite how disappointing it may be to fans of those characters, it was ultimately the right call. The franchise tends to get a little too cute with its callbacks and cameos, and when it indulges in fan service, it really indulges. (There’s a reason why Rise of Skywalker quickly became derided as “written and directed by Reddit.”)

That Star Wars is in constant conversation with its fanbase isn’t inherently bad, and much of it wouldn’t exist without this approach. But the way Andor goes about it is more one-sided, instead reminding audiences that it’s in charge and telling them to meet it on its own terms.

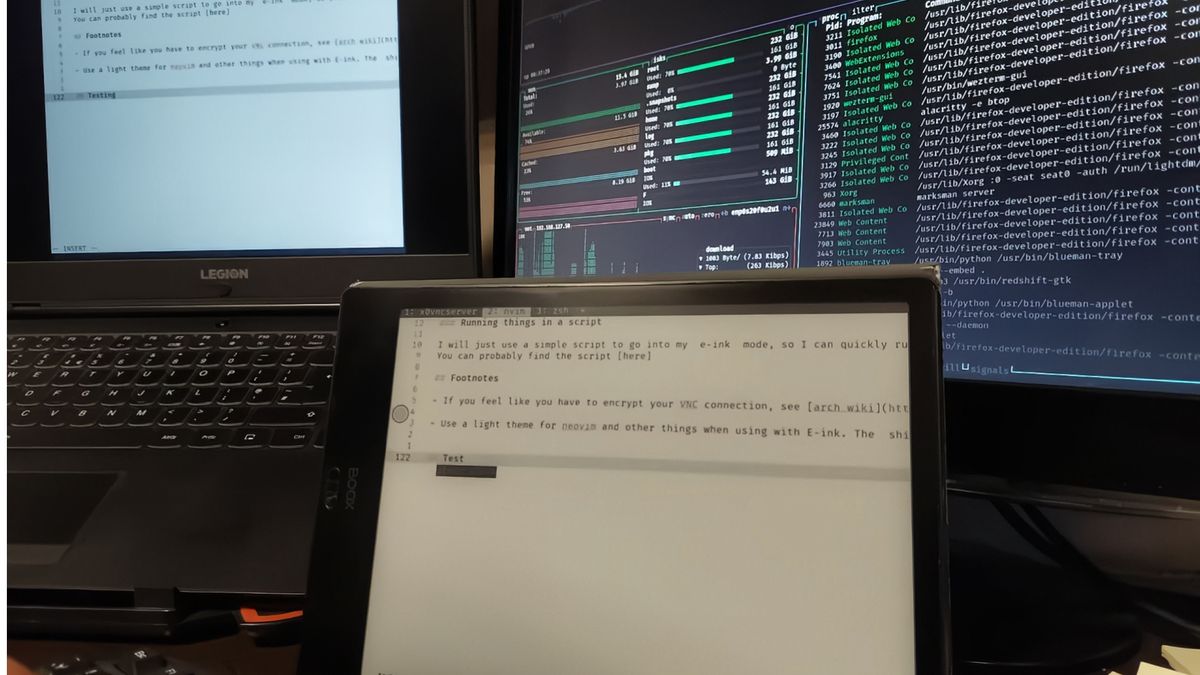

This was, according to Gilroy, a conscious decision: he revealed in 2022 he instructed his writers and crew to treat this like any other show instead of a Star Wars show. “We told people, ‘Do your thing. You’re here because we want you to be real.’ […] It really gets into people’s heads, but to change the lane and do it this way, it takes a little effort,” he said to the Hollywood Reporter.

©Lucasfilm

©LucasfilmIn some ways, it feels like the show was made in isolation from its own mothership franchise and any idea of what the reactions would be like—for better and worse—but it could easily just be how locked in Gilroy and company were during production. He’s on record as taking Star Wars seriously and treating the setting and characters with real, considerate intent. In many cases, that means working ahead of the audience, like crafting Kleya and Luthen’s backstories so viewers wouldn’t think they were sleeping together, or treating Cassian’s missing sister Kerri as a thread in his life that he’ll just have to live with being unsolved.

In another show, or maybe the same show but with more time, Cassian probably would’ve gotten a definitive answer before flying off to begin Rogue One, and with how espionage-focused this all is, Kerri would either have to be a secretive Kleya or a woman in the ISB or another rebel group with a particular interest in him. Those, or making Cass’ childhood droid B2 into his adult droid companion K2SO, would’ve been somewhat understandable (albeit completely strange) soap opera-esque twists in another show, but they wouldn’t be right to how Andor operates.

Fan theories often involve characters getting a happy ending or what they want to some extent, and Andor isn’t really the type of show where those thoughts are allowed to foster and fully take shape. A repeated throughline for many of its characters is their being denied the chance of a future they wanted or may not have realized was possible until it was too late. For the most part, that’s meant a grim fate of some kind awaited them; Syril Karn’s much-predicted change of heart for the Ghor was never going to manifest in some betrayal of Dedra or joining the Rebels—as actor Kyle Soller tells it, being killed was the right outcome for his character. But those who make it through to the show’s end don’t get off unscathed, since their final appearances are punctuated with an undercurrent of bittersweetness or darker, sadder conclusions to their stories.

Andor is a matter-of-fact show, and it isn’t trying to get a deliberate reaction out of audiences the way other shows do, Star Wars or otherwise. It was, first and foremost, concerned with telling the story of Cassian’s growth into a prominent rebel leader and how those caught in his orbit were shaped by his actions. It didn’t care what the viewer thought because it knew it had the goods, and that confidence sure did pay off.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·